In an article in the Telegraph under the title “Europe’s dogmatic ruling class remains wedded to its folly”, Peter Oborne draws the quarrels over Britain’s future in the European Union into relation to age-old philosophical rivalries: “The problem is that European and British leaders tend to come from rival intellectual traditions”:

“In Britain, empiricism – most closely associated with Hume, though its roots can be traced back to William of Ockham and others – is the native inheritance. Empiricism insists that all knowledge of fact must be based on experience. Most European schools of philosophy claim the exact opposite, namely that ideas are the only things that truly exist. This school of metaphysical idealism can be traced back through Hegel (for whom history itself is the realisation of an idea) and Kant to Plato. Anglo-Saxon empiricism and the idealism found on the Continent therefore prescribe directly opposite courses of political conduct.”

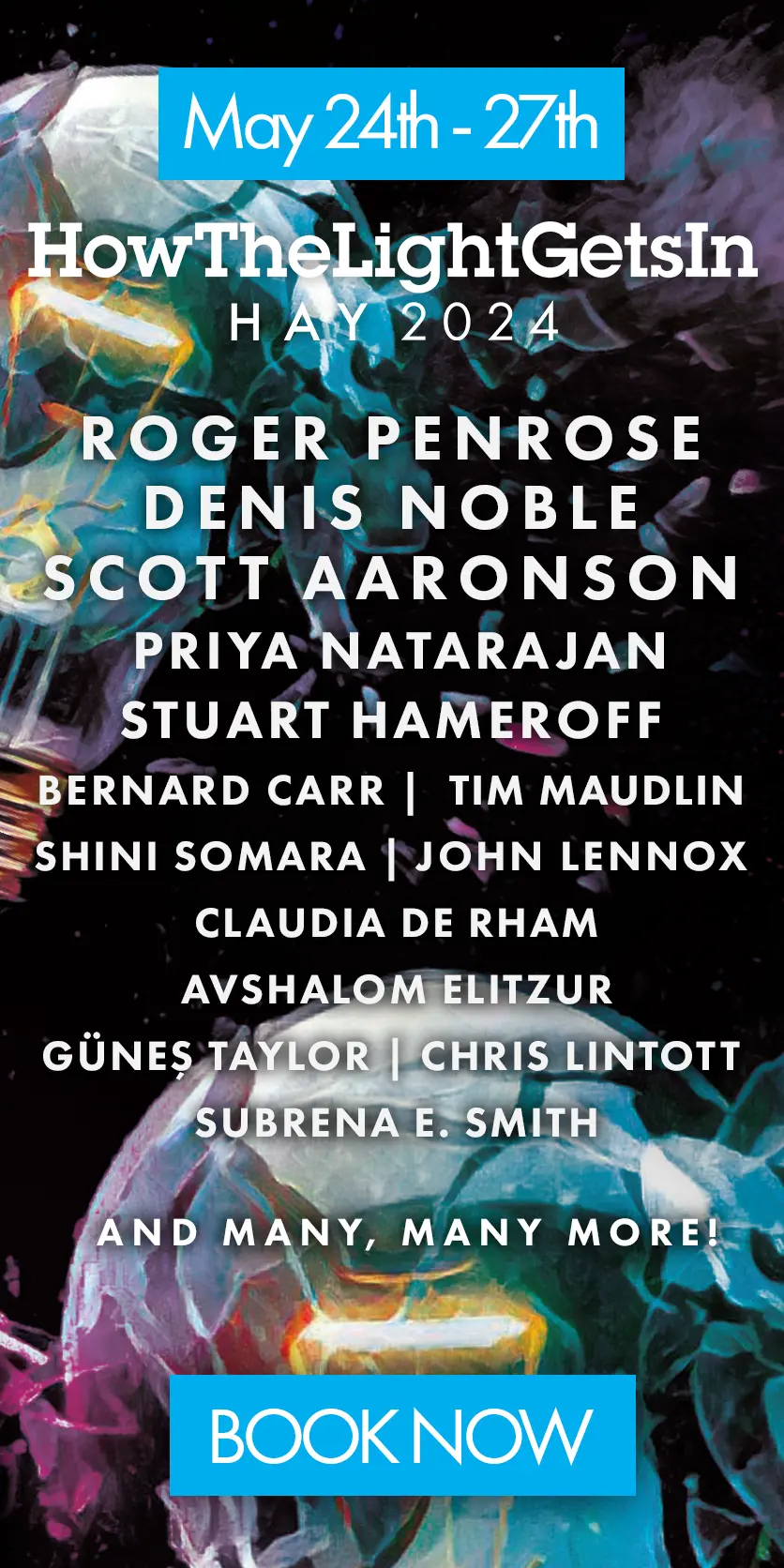

Oborne’s attempt to align contemporary European politics with traditional European philosophy is fascinating. But I don’t think his distinction between idealists and empiricists will do the trick, since it mixes up positions in ontology (Idealists versus Materialists) and in epistemology (Rationalists versus Empiricists). However, I do think that significant philosophical – though non-national – differences are lurking behind today’s major political disputes about European union. Another philosophical distinction, and one which I will be discussing at this year’s philosophy and music festival “HowTheLightGetsIn”, might well be thought to underlie the major political differences concerning Europe’s future.

The distinction at issue grows from rival views of human history. Both positions are likely to understand the trajectory of Europe’s history as involving a transition from a primitive condition to an increasingly civilised one. However, one of these positions regards that transition as having a universal appropriateness for all human beings: the process of civilisation is understood in terms of progressive advances in learning how to live that move towards an ideal form of individual and social life for all.

In his famous essay “Two Concepts of Liberty”, Isaiah Berlin draws a distinction between those who hold this kind of view of history and those who find such grand narratives of emancipation and progress both unbelievable and dangerous. The former group can be said to be inclined towards what Berlin calls a “metaphysical view of politics” because their views are governed by an a priori idea of the proper end of Man. The latter, by contrast, are those who hold what Berlin calls an “empirical view of politics”, claiming to take men as they find them. On the latter approach, Berlin suggests, we come to see that “the ends of men are many, and not all of them are in principle compatible with each other”. Consequently, such a thinker will conclude that “the possibility of conflict - and of tragedy - can never wholly be eliminated from human life, either personal or social.”

Berlin is aware that this sort of view “may madden those who seek for final solutions and single, all-embracing systems, guaranteed to be eternal.” Nevertheless, he is convinced that “it is a conclusion that cannot be escaped by those who, with Kant, have learnt the truth that 'Out of the crooked timber of humanity no straight thing was ever made'.”

It is in these terms that I think we should understand the distinction underlying Oborne's discussion. It is not a contrast between idealists and empiricists. But, in contrast to Skeptics, between those, on the one hand, who cleave to an ideal in which every man is free to make his own “experiment in living”, and those, on the other hand, who think they already have an answer to the question “How to live?” The vital contrast, one might say, is between Experimenters and Dogmatists concerning how to live.

Join the conversation