Raymond Geuss, Agnes Callard, Tommy Curry, Kate Manne, Julian Baggini, Sundar Sarukkai, Maria Balaska, Sara Heinämaa, Robert Sanchez, and Robin R. Wang on contemporary philosophy’s blind spots.

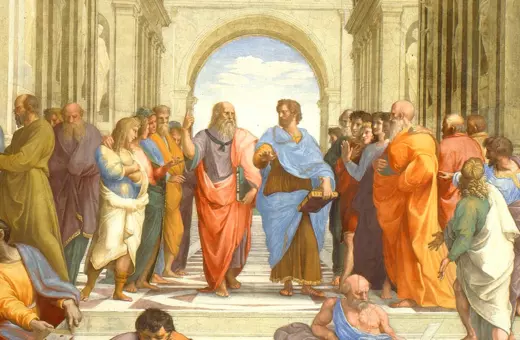

For this year’s World Philosophy Day, we asked ten leading philosophers from around the world, working in different philosophical traditions, what are the most important questions mainstream philosophy ignores or has forgotten about today. With analytic philosophy having dominated the English-speaking world and beyond, we can often forget that there are other philosophical traditions alive and kicking. They operate under different sets of assumptions, take different texts as their starting points, and end up in different places. But even within analytic philosophy, there are philosophers that are pushing the limits of that tradition, asking new and original questions, or re-invigorating an otherwise a-historical line of thought with forgotten but still relevant questions from the past.

Julian Baggini

What is the role of personal judgement in rational thought?

Philosophy's self-image is of rigorously rational thinkers who follow the argument wherever it leads, as though they had no control over its direction. It's a vision of philosophy that assumes it has an objectivity akin to science. But I think everyone knows that good philosophy cannot be pinned down to formal arguments that every intelligent person would have to agree with, like a bit of mathematics. Everyone knows that philosophers exercise judgement and some exercise it better than others. But to address this head on requires admitting that the 'rigour' of philosophy is not as it seems. So it remains philosophy's dirty secret.

Julian Baggini is a british philosopher, journalist and author of over 20 philosophical books, including The Edge of Reason.

Maria Balaska

What is 'nothing', and how can our experience of anxiety shed light on it?

Science wants to know nothing of the nothing, Martin Heidegger writes in 1929. His reproach is not, however, directed to science; after all, science must restrict itself to cases of ‘something’ that it investigates, calculates, and so on. The reproach is directed against philosophy insofar as it is determined by science, and it is today as valid as it was a century ago. But how can there be a reproach, if ‘nothing’ means strictly speaking nothing?

Nothing’s near absence from mainstream philosophy may at first seem understandable. It leads to paradoxes, or even to ‘mere nonsense’, when one takes a Rudolf Carnap view on language. Hence it has been preferable to think of nothing as the logical operation of negation (an odd bit of our notation, like the number zero) or to link it to an absent something (death, destruction, annihilation, and other related dark concepts).

But those thinkers, like Kierkegaard and Heidegger, who insist that the nothing is prior to an act of the intellect (negation) and that it is not an absent something either, direct our attention elsewhere. Nothing is primarily encountered, rather than conceived or inferred; and this encounter takes place in certain moods, not in the vacuum of the philosopher’s mind-lab.

They name anxiety as one such mood. Distinct from fear, that responds to something (spiders, flying, commitment, death), anxiety is about nothing. Although, at the level of entities, nothing unusual has taken place, it feels like the whole that sustained us withdraws and we withdraw from ourselves. Things are still there individually, yet they slip away as a whole. What can we learn from the fact that encounters with nothing can affect us so profoundly? To begin to answer, philosophy must allow itself to become anxious about nothing.

Join the conversation