Jasper Fforde is a best-selling novelist who rose to prominence on the back of his 2001 debut novel, The Eyre Affair, which unleashed a time-travelling detective named Thursday Next into the unsuspecting world of Charlotte Bronte's Jane Eyre. Since then, Fforde has written seven books in the same series, each one characterised by a playful approach to literary allusion, as well as several other novels and short stories.

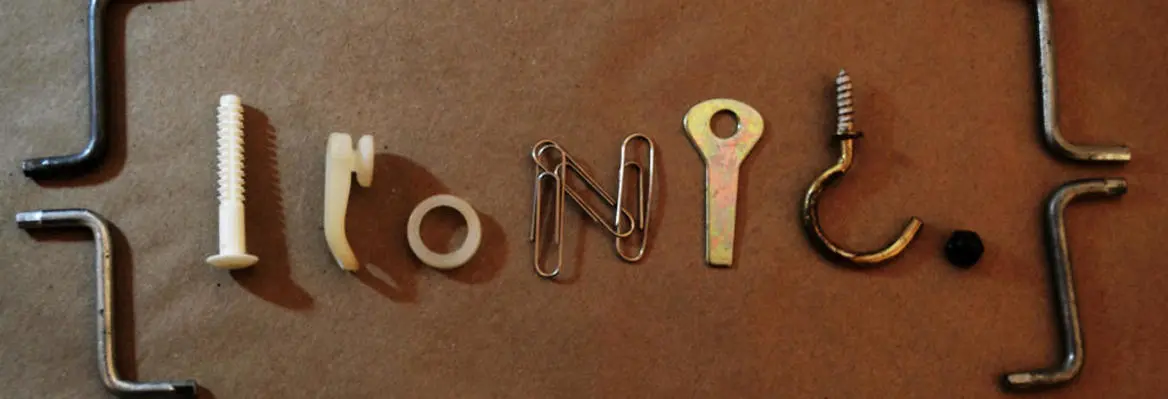

As a new scientific study into the function of irony has been published in the Journal of Experimental Psychology, we spoke to Fforde about the importance of irony in his work, and what science can (or can't) offer to our understanding of literature.

How central is irony in your own work?

Using irony is something I do a lot, but it never occurs to me to think: “hah, this is ironic” when I am writing; I simply write what I think will be of interest, and strive to amuse and engage the reader. Irony, pathos, inferred narrative, foreshadowing, intertexuality: yes, terrific – but when writing, the labels evaporate, the same way as a mechanic will be thinking about the reluctant bolt, and not the fact that he's using a spanner to undo it.

Is it possible to draw a rigorous line of delineation between the ironic and the literal?

A line is hard to draw between anything with humans, particularly when interpretation is concerned. Since irony generally requires some sort of unknown knowledge on behalf of the listener, the possibilities of even accidental irony are manifold. After all, the speaker cannot know what the listener does or doesn't know. Even literal language in itself is not devoid of irony: 1984's 'Newspeak' posits the idea that stripping a language of all subtlety and subtext can somehow control freedom of thought, when it is abundantly clear from Winston Smith's actions that it cannot.

Academic study has many pitfalls when it attempts to bottle and label human interactions, which evolves with staggering levels of speed and complexity. I heard of a linguistics professor who boldly declaimed that while a double negative can mean a negative and also a positive, a double positive can only mean a positive, upon which someone at the back said: “yeah, right.” End of lecture.

While science can clearly offer us many paths to a greater understanding of language, do you think it can offer much when it comes to reading literature?

Science isn't a tangible object, of course, it's a discipline, a method, and while attempting to explain why something might be funny or not funny or ironic or not ironic might be of some use to academics, I'm not convinced it's of much use to the reading public at large. Reading fiction is an emotional act, not an academic one. Fiction is a gateway to what makes us human, and in its very finest exponents, barely touches the mind as it goes all the way to the soul. I would counter that if there are any obstructions on the way – a need to understand varying forms of irony, for instance – then the story will stumble, with potentially negative results.

But having said that, I don't believe understanding language is without merit – language is the proxy of our thoughts, and on occasion needs to be trimmed and reassessed. But more in the playing field of, say, social equality than fiction. As soon as you start thinking how a story works, then the magic is already partly gone.

Join the conversation