Western philosophy is often abstract and disconnected from the real ethical problems we face today. Emmanuel Chiwetalu Ossai and Lloyd Strickland argue that the African philosophy of ubuntu, with its emphasis on community, interconnectedness, and practical application of ethical principles, offers a compelling alternative.

Western philosophy has long faced questions about its relevance, and even about its self-indulgence. It is not hard to see why. Some philosophical questions seem trivial and esoteric, of little interest except to a handful of other philosophers (think: do holes exist?). Philosophical theories are often opaque, dressed up in jargon that only professional philosophers understand. And a great deal of philosophy is concerned with abstract and theoretical matters with little to no practical import. Even in ethical matters, the abstract is often favoured over the concrete. Western ethical frameworks such as utilitarianism and deontology are typically treated through theoretical examples and thought experiments, such as the trolley problem, forced organ transplants, and whether it’s permissible to lie to an axe murderer. These might be a source of fun, amusement, and lively discussions in seminar rooms, but removed as they are from everyday life, such thought-experiments help to reinforce the charge that philosophy is disconnected from real-world problems or practical issues.

Of course, such a charge cannot stick to all western philosophy. The ancient Greek and Roman philosophy of Stoicism is an obvious exception. Stoicism emphasizes the cultivation of inner strength, resilience, and virtue in response to life’s challenges. It encourages living in accordance with reason, wisdom, and the pursuit of moral excellence, with the aim of teaching people to focus on what is within their control and accept what is not. Here, then, is a western philosophy that is not concerned with dry, abstract, theoretical matters, but with everyday life and its challenges. It is also a philosophy that was lived, such that its principles shaped and informed people’s own existence and their navigation of the world around them. What is more, Stoicism remains a lived philosophy today, as is clear from the examples of the American prisoner of war James Stockdale and the British illusionist Derren Brown, both of whom publicly have promoted Stoicism and professed to live by its principles. However, it is difficult to say how widely Stoicism is practised beyond this handful of high-profile proponents.

SUGGESTED READING

What African Philosophy Can Teach You About the Good Life

By Omedi Ochieng

SUGGESTED READING

What African Philosophy Can Teach You About the Good Life

By Omedi Ochieng

Yet there are examples of lived philosophies that have been and still are practised widely: a prime example is Ubuntu philosophy. The term “Ubuntu” has various interpretations. Among the Bantu-speaking people of southern Africa, where it has its roots, it means ‘humanness’ – the state of being human. The Bantu also associate the term with a much deeper relational meaning: The level of Ubuntu that one has depends on how one behaves towards other humans in ways that recognise the interconnectedness, interdependency, and the promotion of community over the individual . In the words of the prominent African philosopher Pascah Mungwini, Ubuntu is rooted in the realization that ‘human beings must assume the responsibility of creating a humane environment within which they exist together’.

___

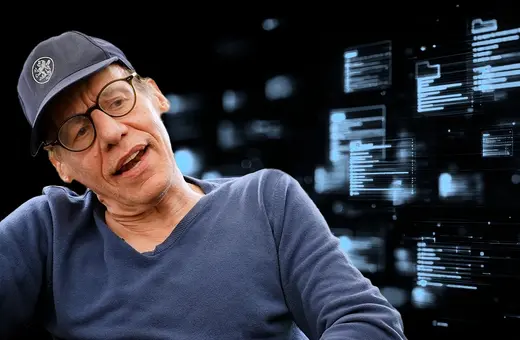

Children are taught the principles of Ubuntu using riddles and stories

___

Interpretations of Ubuntu often describe it using Southern African maxims, such as the Zulu phrase umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu, which means that a person is a person through other persons, or that a person depends on others to be a person.

Join the conversation