Throughout history humans have constructed grand narratives to make sense of the world around them – Christianity, the Enlightenment, and Marxism, to name just a few. But in our age of skepticism, belief in grand narratives has declined. We are left with no clear story about who we are or where we are going. In this article, Matt McManus argues that the sense of meaningless and despair caused by the decline of grand narratives has been coopted by nationalist and authoritarian movements. McManus proposes that the answer is not another grand narrative, but a communal politics to fill the void of our postmodern age.

In his classic book The Postmodern Condition the French philosopher Jean Francois Lyotard described postmodernity in terms of declining faith in “meta” or “grand” narratives. As the name suggests grand narratives are not ordinary stories. They are instead epic accounts of the world which try to encompass enormous swathes of events. Often transdisciplinary and combining moral purpose with descriptive ambition, successful grand narratives have long had an enduring grip on the imagination. They include many of the world’s religions, which account for everything from the creation of the world to the higher ends human beings are supposed to pursue. Many teleological visions of history are couched in grand narratives, including those that emerged out of the early and mature Enlightenment. This includes everything from liberal paeans to the inexorability of progress through the spread of rationality, to orthodox Marxist convictions about the inevitable triumph of the working classes and the emancipation of human potential through an ordained transition to communism. Often Lyotard and his followers conceive of grand narratives as fundamentally optimistic. But they can also take the form of more reactionary laments about decline and fall. From Nietzsche’s anxieties about the onset of the “last man” at the end of a long process of historical decadence, to Eric Voeglin’s borderline Biblical account of modernity’s descent in secular Gnosticism, reactionary grand narratives of loss are a dime a dozen.

___

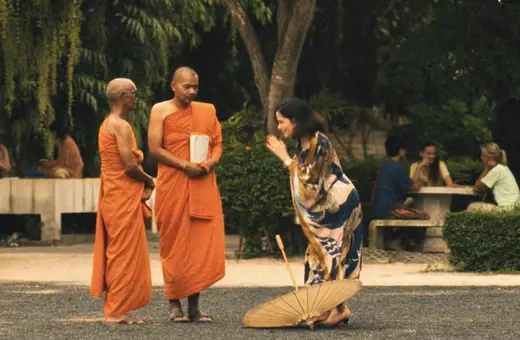

In the 20th century there was a transition from modernity to post-modernity defined by declining public faith in all forms of grand narratives.

___

The Fall of Grand Narratives

Lyotard’s core point in The Postmodern Condition was that at some point in the 20th century there was a transition from modernity to post-modernity defined by declining public faith in all forms of grand narratives. Incredulity replaced optimism, and faith transvaluated into cynicism. This of course didn’t mean that people stopped thinking through the world in terms of narratives. Lyotard recognized that we are inherently story-telling creatures, whether we’re narrativizing the immanentization of the eschaton or our bad experiences at a family reunion. But grand narratives were no longer the kinds of stories anyone found appealing; our deepening incredulity meant that they hardly even made sense to post-modern generations except as some kind of bizarre relic. Instead, inspired by the Ludwig Wittgenstein of Philosophical Investigations, Lyotard felt that the stories we would now tell – whether about truth, morality, or the meaning of the world – would be far more small scale. Different communities and individuals would tell themselves distinct stories that reflected their forms of life. This would in turn reflect the deepening pluralism characteristic of late 20th-century society, where comparative cultural homogeneity was splintering under enormous pressures ranging from political discontent to the radical transformations enacted by capitalism. So instead of rallying around big, unifying narratives about religious salvation or secular progress, different subcultures would organize by telling themselves stories about everything from sports to who the best punk band was.

Join the conversation