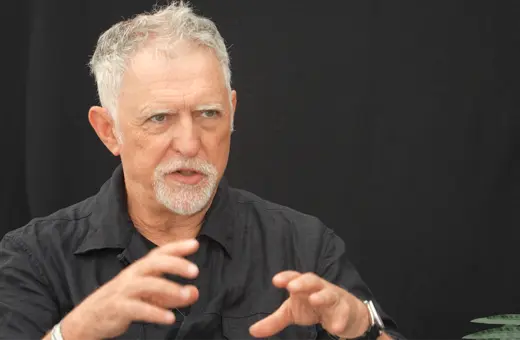

The hard problem of consciousness has puzzled philosophers and neuroscientists alike for decades. Here a philosopher, Riccardo Manzotti, and a neuroscientist, Anil Seth, meet to discuss consciousness, the hallucination of reality, and whether consciousness is inside or outside the brain.

I met Anil Seth many years ago. I think it was 2003, give or take. We had the first of many discussions about the nature of conscious experience. Although we share many ideas, we are also very different in the conclusions we draw. He takes consciousness to be an emergent phenomenon taking place inside the brain and I take consciousness to be the external world impinging on the brain. He believes that perception is a reliable hallucination, I believe hallucinations are a form of perception. This shows the richness of scientific debates on controversial topics such as consciousness, where scientists with different approaches and insights can benefit from a candid discussion. It is common knowledge that consciousness is still a great mystery to science and that although there has been a tremendous growth in scientific work on consciousness in the last decade, there is still no accepted theory on how consciousness arises in the physical world.

Anil Seth has been involved in the study of consciousness for 30 years. As a young assistant, he worked with Nobel laureate Gerard Edelman and then moved to the United Kingdom, where he eventually became director of the Sussex Centre for Consciousness Science. He has published hundreds of articles and his latest book, Being You, is an international bestseller that has won umpteen awards. The book has helped make Seth a world-renowned celebrity in science. But with great power comes great responsibility, and so I am pleased to have a dialog with Anil Seth about his views all the more because our approaches are apparently so distant.

Given such a unique combination of friendship and differences, I very much look forward to our dialogue.

Hi Anil, how are you? I am just holding in my hands the new copy of your book, which has just been published everywhere and eventually in Italian. I see that it was incredibly successful: a Book of the Year for Bloomberg, the Guardian, the Financial Times and the Economist! That's very impressive for a scientist! What do you think is the secret of this success?

___

At the end of this road, my hope is that the ‘hard problem’ question of why there is phenomenal character at all will fade away, disappearing in a puff of metaphysical smoke.

___

Hi Riccardo – I’m doing well, and I hope that you are too. It has been a long time – but one of the great privileges of a life in academia is the pleasure of conversations that unfold over years or even, as in our case, decades. I am very happy to have the chance to continue our conversation – and productive disagreement – about the nature of consciousness.

Join the conversation