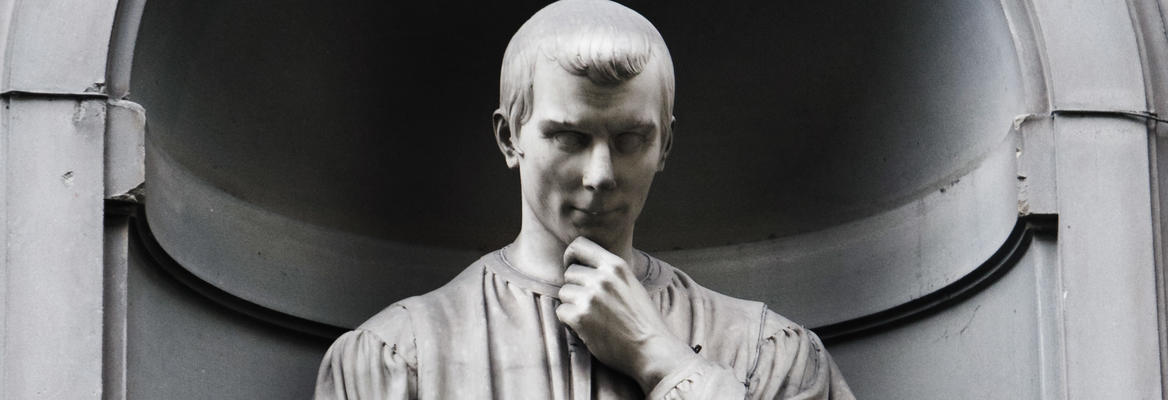

We tend to think of liberal democracies as secular. But religious ideas are increasingly gaining power over our politics. Populist leaders are deified, and religious beliefs are informing key political debates like abortion and gay marriage. Stuart Grey argues that Renaissance philosopher Nicolo Machiaveli and Ancient Indian thinker Kautilya explain how supposedly religion-free liberal politics became coopted by theology.

In modern secular democracies such as the United States we generally congratulate ourselves for not having a theologically based form of governance—but is this a smokescreen? Historically, liberal democracies with citizen equality and the rule of law were implemented in response to the arbitrary whim of elites, be they religious, economic or aristocratic. In many Western nations, the rule of law, legitimised through the free consent of the governed, was established in response to the wars of religion in Europe during the medieval and early modern periods. Liberal philosophical tenets and representative democracy were then combined in early modern “contract theory,” which allowed communities to conceive how they might legitimate political authority without a deity. The achievement was a form of governance grounded in a social contract among theoretically free and equal citizens that possessed natural rights, requiring these citizens to tolerate deep doctrinal disagreements so that they could achieve a peaceable sphere in which to pursue their chosen individual conceptions of the good. But even though it may seem that we have extricated God from politics, his influence was never truly stamped out.

Political theory makes a distinction between those who are ‘in’ authority versus ‘an’ authority. Those ‘in’ authority possess their authority by virtue of the office they hold, so that power and legitimacy are invested in the office and not the person. In contrast, those who are ‘an’ authority possess their authority by virtue of some special characteristic, knowledge, or attribute that is understood to justify the position they hold. The purported upshot of having a system wherein political power is invested in offices, as opposed to personal characteristics, is that political legitimacy need not rely entirely on the personal attributes of fallible, partial, or corrupt human beings, instead relying on a system of offices and rule of law. Potentially corrupt or self-interested politicians can then be shuttled in and out of authoritative offices at the behest of citizens during regular elections. But what if assuming that this is how things work prevents us from seeing what might be happening beneath the surface of contemporary American politics?

___

The contrast between Kautilyan and Machiavelli proves useful because it allows us to assess the comparative realist measures that could be justified within a secular versus theological form of realism.

___

Join the conversation