‘Authenticity’ is a quality that has drawn a polarised response in the history of philosophy, especially in discussions of the self. Is there something that captures who I really am? And if so, should I try to find out what that is? And if not, then what’s all the fuss about? At the outset, it’s useful to distinguish two senses in which there might be an ‘authentic self’: a naturalistic sense and a more strictly normative one.

The naturalistic sense of authenticity appears in the idea that each person possesses an ‘essential nature’, which may or may not be expressed adequately in the conduct of life. This is a familiar idea in both Greek and Christian culture, though explained somewhat differently. The Greeks had a much stronger sense that in the fullness of time your authentic self is always revealed – often to tragic effect. In contrast, Christian culture admits the possibility that your authentic self may remain hidden indefinitely, especially if you are never offered an opportunity for salvation.

In the modern period, Romanticism turned authenticity into a personal duty: the quest for the ‘real me’. This too may have tragic – or exhilarating – consequences. But in any case, as Frank Sinatra would say, “I did it my way”. So understood, authenticity amounts to a coming to terms with oneself: a moment of ultimate self-consciousness, as Hegel and other idealist thinkers conceptualised it.

However, by turning authenticity into a quest of personal discovery, the Romantics also seemed to suggest that the journey was itself a process of ‘authenticating’ the self. In other words, just as important as acting as you really are is knowing that that’s what you’re doing. At that point, the ‘authentic self’ becomes a more normative idea, one tied to being responsible for who one is, or ‘owning’ one’s actions, as it’s often put today. It marks a subtle shift from the ‘my’ to the ‘I’ in ‘I did it my way’.

The two centuries since Romanticism have witnessed a gradual decline in the naturalistic conception of the authentic self, with Freud perhaps providing the last – and ironic – twist in that tale. Yet, the normative side has remained strong, and, if anything, has grown stronger. Existentialism may be understood as based on a conception of authenticity as sheer self-affirmation, which puts a brave face on a destiny beyond one’s control that may well lay to waste even the best made of plans.

But of course, if one doesn’t long for an authentic self in the first place, the existentialist’s situation doesn’t look quite so bleak. Indeed, one might associate the lack of an essential nature with the freedom to be as one wishes, for as long as one wishes. In The Fall of Public Man, the sociologist Richard Sennett famously argued that this was the spirit in which the public sphere first flourished in the Enlightenment, a generation or two before Romanticism took hold.

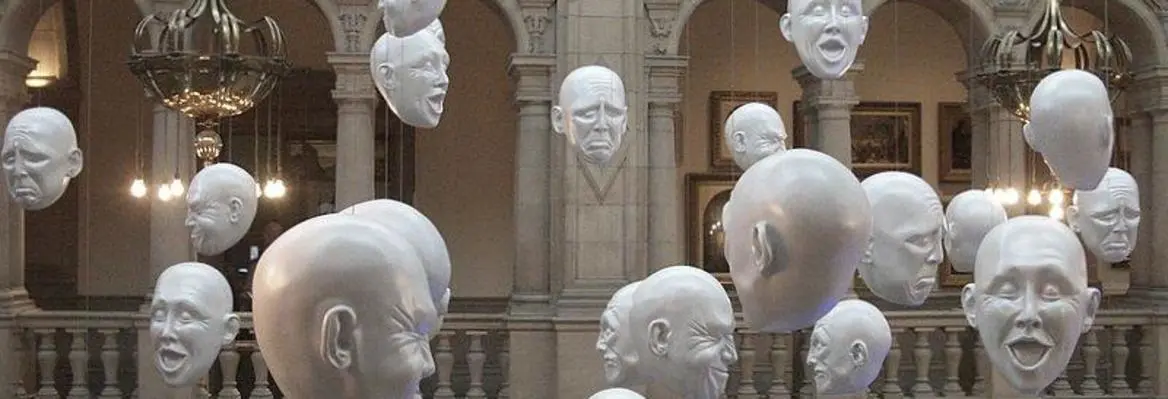

Anticipating the new sense of class mobility that would come to characterise the modern era, Enlightenment culture celebrated experimentation with new identities, as exemplified in comedies of manners and satires. These genres played with the original sense of persona in Greek drama: namely, the actor’s mask. In this context, the fact that things may never quite be as they seem was less a source of Cartesian consternation than the opening up of a field of playful possibilities, the source of the period’s famed sense of wit.

Join the conversation