Is our personal identity just the particular make up of our physical bodies at a particular point in time? And if so, would a teletransporter that replicated our physical bodies on Mars preserve our personal identity? Thought experiments and transhumanist sci-fi technological dreams such as this are deceptive means of doing philosophy and should be kept in Hollywood and marketing campaigns, writes Nicholas Agar.

In his 1984 philosophical classic Reasons and Persons Derek Parfit tells a story about a fantastical futuristic technology – the Teletransporter.

I enter the Teletransporter. I have been to Mars before, but only by the old method, a space-ship journey taking several weeks. This machine will send me at the speed of light. I merely have to press the green button. Like others, I am nervous. Will it work? I remind myself what I have been told to expect. When I press the button, I shall lose consciousness, and then wake up at what seems a moment later. In fact I shall have been unconscious for about an hour. The Scanner here on Earth will destroy my brain and body, while recording the exact states of all of my cells. It will then transmit this information by radio. Travelling at the speed of light, the message will take three minutes to reach the Replicator on Mars. This will then create, out of new matter, a brain and body exactly like mine. It will be in this body that I shall wake up.

Though I believe that this is what will happen, I still hesitate. But then I remember seeing my wife grin when, at breakfast today, I revealed my nervousness. As she reminded me, she has been often teletransported, and there is nothing wrong with her. I press the button. As predicted, I lose and seem at once to regain consciousness, but in a different cubicle. Examining my new body, I find no change at all.

Parfit uses the teletransporter story to launch a philosophical assault on common-sense beliefs about what we are. A series of variations of the teletransporter story demonstrate that we are not individuals whose survival consists in the preservation of our personal identities over time. The seemingly earnest question – ‘after many years of Alzheimer’s disease would it still be me?’ – relies on a false assumption.

I think we should view Parfit’s story as a comparatively early instance of philosophy by sci-fi. And for that reason, we should distrust our intuitive reactions to it.

These are far-reaching challenges to common-sense about what we are, all on the basis of a fantastical story. I think we should view Parfit’s story as a comparatively early instance of philosophy by sci-fi. And for that reason, we should distrust our intuitive reactions to it.

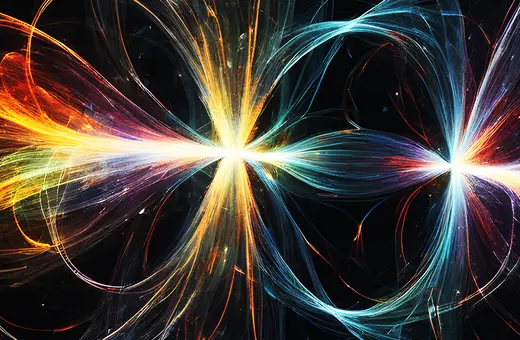

We are a long way off teletransporting persons. But the teletransporter doesn’t seem to violate any law of physics. There are proofs of concept in the quantum world in which the state of one particle can be instantaneously teleported to another by way of quantum entanglement. A retelling of Parfit’s story that was a bit more focused on the science might count as hard science fiction. We might compare it with the more pessimistic account in Kameron Hurley’s 2019 novel The Light Brigade. Her teletransportees suffer a variety of accidents more upsetting that any Parfit describes. They arrive on planetary surfaces missing vital organs or with their memories scrambled.

Join the conversation