Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, or so we are told. Filippo Contesi, Enrico Terrone, Marta Campdelacreu and Genoveva Martí argue that the traditional view in philosophy of art is that, whilst most of us claim to believe that beauty is subjective, we actually act as though it is objective. The true problem of aesthetics then, is not whether or not we believe that beauty is in the eye of the beholder, but why our behaviour around beauty doesn’t match up with our stated beliefs. Beauty, it seems, is more than skin-deep.

If we had a penny for every time we hear the saying “Beauty is in the eye of the beholder”... Since at least the 18th century, philosophers and common people alike have pondered the question of whether or not the proverb is true. Some have answered one way, others the other. However, philosophers have typically agreed that, in general, people often claim that the proverb is true and that our aesthetic preferences are indeed a matter of individual or subjective taste. Moreover, as suggested by the use of the (gustatory) taste metaphor to talk about aesthetic matters, there appears to be something distinctly subjective to aesthetic experience. On the other hand, philosophers also typically agree that people often also do things that suggest they do not really believe all tastes are equally good. For instance, we read what film critics say before deciding what to see at the cinema, or we argue about who is the best Hispanophone novelist of our generation by trying to provide objective (or at least intersubjective) reasons. Reconciling these subjective and objective intuitions about aesthetic matters is a key question for the aesthetics scholar. Indeed, a prominent contemporary philosopher deems it as the “Big Question in aesthetics”. An international group of scholars, led by Florian Cova, have recently questioned the traditional philosophical consensus about aesthetic matters. They suggest that, by getting up of their proverbial armchair and using more rigorous experimental methods instead, philosophers would have to accept that, generally speaking, people only ever consider aesthetic judgements as subjective. We are doubtful.

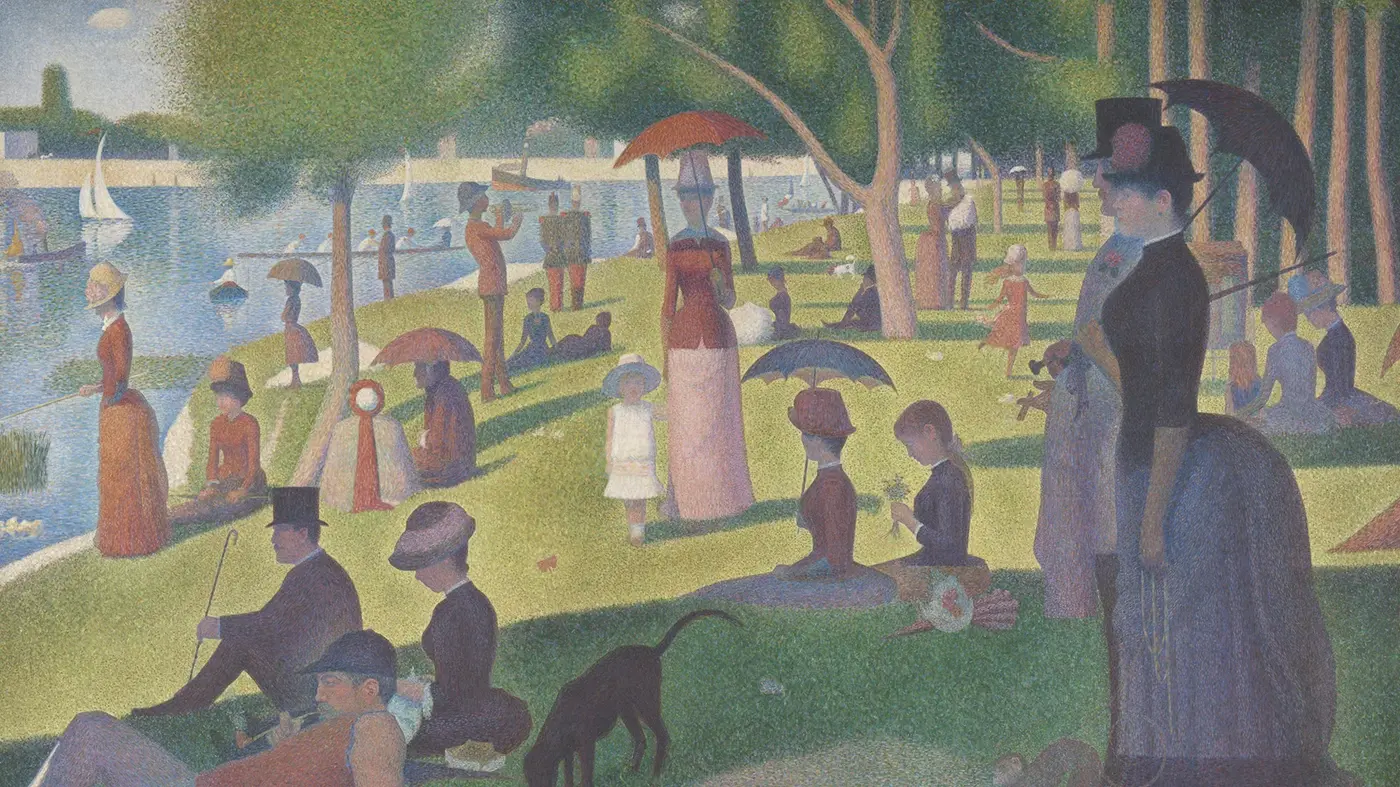

In their experimental study, Cova et al. tested 2,392 participants in nineteen countries across four continents. The participants were invited to describe something they find very beautiful and imagine someone disagreeing with them. Cova et al. left it to participants to choose which items to describe and, unfortunately, their paper does not provide any details as to what those items were. In a previous study conducted in the Latin Quarter in Paris, however, some of the same experimenters provided their own examples to participants, including famous works of art such as the Mona Lisa and Beethoven’s For Elise, examples of natural beauty such as the singing of the nightingale or Niagara falls, as well as examples of beautiful people. That study still found similar results to the bigger, international study. In the latter, participants were asked to choose one among the following three options, specifying how certain they were of their choice:

1. One of you is correct while the other is not.

2. Both of you are correct.

3. Neither is correct. It makes no sense to talk about correctness in this situation.

___

The problem is that people say that beauty is in the eye of the beholder but then they behave as if it should be in everyone’s eyes.

___

Join the conversation