Beckett’s work has become increasingly topical. Over the past six months, comparisons between the British government’s Brexit negotiations and Endgame have cropped up regularly in the press, and Waiting for Godot has been staged at the Irish border between the counties of Cavan and Fermanagh. Prior to that, Beckett’s canonical plays on stasis, inaction and circularity were regularly evoked in accounts of the Syrian Civil War and articles describing the endless plight of Syrian refugees. And prior to that, the idea that ‘this’ – any international crisis or difficult episode in European or American politics – ‘is like Waiting for Godot’ provided many journalists with some convenient one-liners. Everyone is waiting, nothing happens, and no one knows what to do: who else but Beckett can help us think about that?

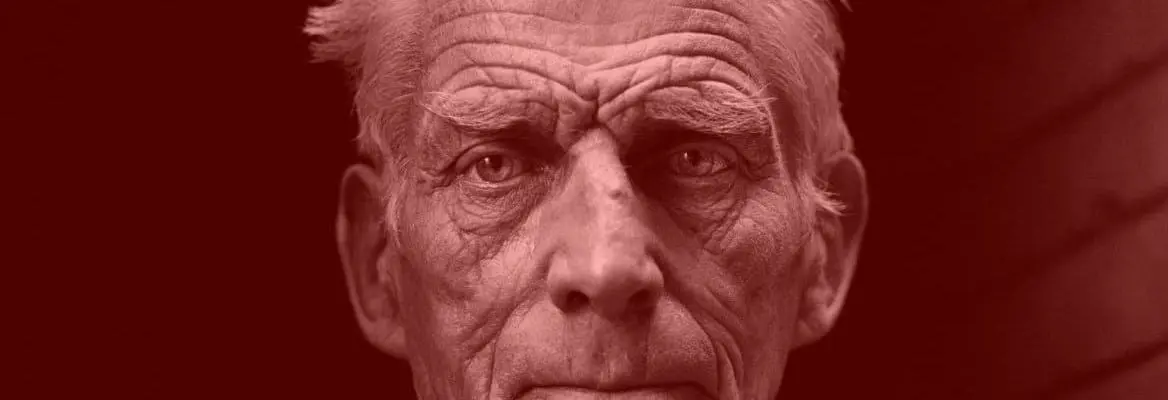

The great paradox is that, on the surface, there seems to be little about Beckett’s work that might enable us to think about politics. His texts deal with uncertainty, displacement and postponement – ideas that are not easily compatible with other types of writing that openly define themselves as political. He has long been thought of as someone who had a deeply abstract way of thinking and was only interested in pure philosophical problems, rather than the problems of the world in which he lived. However, to many among his acquaintances, he came across rather differently: as someone who had an instinctive and deep understanding of pain and suffering, and as someone who knew that times of genuine political tension also bring to light many otherwise hidden truths. He was deeply interested in those moments when what appears to be the set course of history is overturned, and witnessed many such moments over the course of his lifetime.

To some, the situations represented in his work – in his plays in particular – can seem divorced from any recognisable reality. To others, however, the situations of torture, dispossession and subjugation that Beckett’s work depicts are intimately familiar, and its insights into the importance of memory, courage and solidarity are unrivalled. When war and conflict edge closer, Beckett’s writing becomes strangely real and visceral. Many across the world have seen, and continue to see, deep and immediate political resonances in a body of work revolving around ruins, ashes, mud and stones, around waiting and suffering, and around terror, devastation, internment and forced exile.

___

"When war and conflict edge closer, Beckett’s writing becomes strangely real and visceral"

___

The political knowledge that the work carries is a political knowledge that Beckett acquired in the hard way, through experience and observation. The wars and severe political convulsions that made modern Europe shaped his worldview, and he had an unusually extended knowledge of what war does to nations and to peoples. The key themes in his writing – violence, exploitation, dispossession – are politically profound, yet the writing itself doesn’t conform with what is normally expected of openly politicised literature. We can’t expect to find directly identifiable, unambiguous representations of real events in Beckett. What we get are evocations, layers, suggestions, echoes, cultural ciphers, lone allusions. It is clear from the manner in which he wrote that he sought inspiration in the world he knew, and that the political tensions and tragedies that he witnessed were often what inspired him to write in the first place; yet, at the same time, he actively wrote all of this out, and avoided describing specific events directly.

Join the conversation