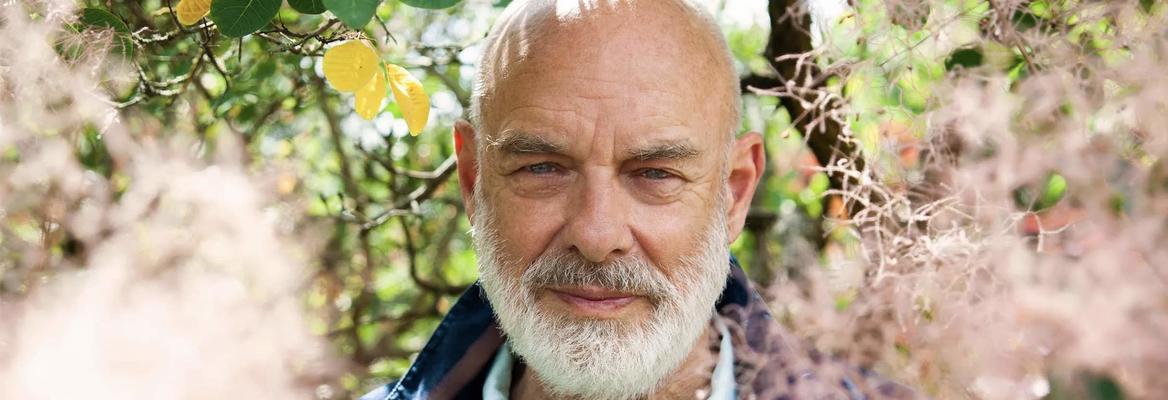

Brian Eno is one of the most decorated musicians of his generation. More than this though, he is considered a pioneer within the artistic community. His exploration of different mediums, genres and technologies is indicative of his undying curiosity to explore the boundaries of art, and how it can function in the world. In this exclusive interview for the IAI, Eno unpacks the nature of art, and how it is best mobilised as a tool for inspiring social and political change

The mixing of ‘Art’ and ‘Progress’ makes for a curious potion. When we consider the latter term, we tend to associate it with technological advancement, or perhaps the promotion of liberal values within society. Yet with art it seems a bit harder to decipher. From one perspective, we can examine the capacity of art as a tool for making social and political progress. Artists can often serve as powerful voices for social causes and help to make vivid the most sobering of truths. Another way of combining art with progress may encourage us to consider the notion of whether art, as a discipline, improves upon itself. A rather contentious narrative, given the fact that art seems to represent a pocket of nostalgia, with many people longing for the classical composers, old masters, and epic poets of bygone times. I began by asking Eno where he stood on the latter of these two.

‘In terms of the way I think about art and the way it works in society’, Eno admitted, ‘some meanings of “progress” as a term don’t make sense’. When we consider it in its most common sense, i.e. of things improving, Eno asserts that ‘art is not related to that at all. Art is a response to how we live, where we live, and what we feel about those things. It’s always a kind of process of imagining different worlds and the feelings we’d have about them’. For Eno then, art is about experimentation, exploring hypothetical lands, and being attentive to the thoughts and feelings they inspire within us.

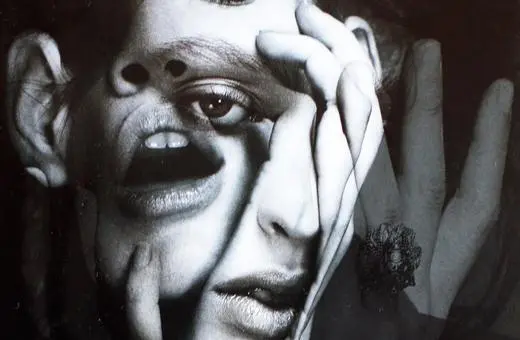

___

The best way to look at it is that technology is just an extension of ourselves.

___

Although Eno was keen to move away from seeing the evolution of art within any kind of hierarchical structure, we do nonetheless continue to hold art criticism as a valuable practice. It must be the case then that certain works, and the worlds they create, are intrinsically better than others? Eno was also keen to reject this line of thought. ‘One criticism levelled at art’, he mused, ‘is that it is dismissed as being escapist; that it takes us out of this world. But I also think, what’s wrong with escaping? We do it all the time; we go on holiday, daydream. So, in light of this, I don’t think that we can really say that some worlds are more crucial than others’.

I was keen to pick up on the relationship between art and emotion, which is seemingly placed at the kernel of Eno’s thinking. And the significance of this cannot be underestimated, since it is emotion which, according to Eno, drives our most important life decisions. ‘Much of human knowledge is based on feelings. We think knowledge is evidential and deduction. But when we think about our most important decisions; what job we want to do, who you live with. For those of us with the luxury of choice, we make these decisions not by cold hard calculation, but rather our emotional responses to things’.

Join the conversation