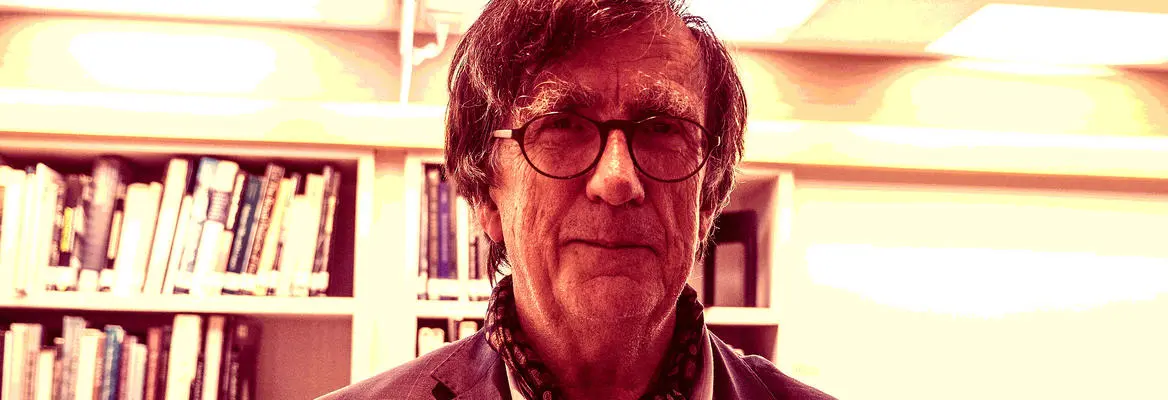

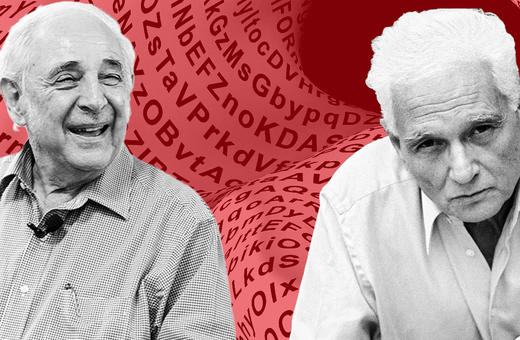

Bruno Latour, a leading French intellectual who died on October 9, posed a major challenge to modern philosophy’s key assumption: the existence of a distinction between the human subject and the world. His radical alternative suggestion of seeing the world as a collection of actors interacting with each other offered a new framework for understanding science, politics, and the environmental crisis, writes philosopher and Bruno Latour’s intellectual biographer, Graham Harman.

With the death of Bruno Latour from cancer on October 9, the world lost a prominent and paradoxical figure whose deepest contributions are not yet well understood. In one sense it would be absurd to call him “unappreciated,” given his receipt of the 2013 Holberg Prize and 2021 Kyoto Prize, his nearly 300,000 citations by other scholars, and his vast global network of admirers and co-workers. But like so many pivotal intellectuals, Latour was a peg who never quite fit the most prestigious holes. Blocked by enemies from potential appointments at Princeton and the Collège de France, he spent most of his career at the School of Mines in Paris before a late move to Sciences Po in the same city.

SUGGESTED READING

An unnatural divide

By Graham Harman

SUGGESTED READING

An unnatural divide

By Graham Harman

A practicing Catholic who moved with ease in the de rigueur atheism of contemporary thought, Latour eventually developed a system of thought that was basically secular in spirit despite the place reserved for religion near its core. Scolded by American science warriors as the “social constructionist” he never quite was, in France he was struck on the opposite flank by the disciples of Pierre Bourdieu, who viewed his fascination with non-human actors as a form of reactionary realism.

___

The reason for Latour's relative lack of success with philosophy readers so far is also the reason for his inevitable future importance in the field: the blow he strikes against the central assumption of modern philosophy.

___

Tweeting the news of Latour’s passing, French President Emmanuel Macron rightly noted that Latour was recognized abroad before it happened at home. Indeed, despite pronounced French elements in his personality and lifestyle, Latour was in many ways more typically Anglo-Saxon, and some of his most important books appeared first in English. But perhaps the greatest paradox of his career was the contrast between his iconic status in the social sciences and his still minimal impact in philosophy, a field where his hopes of influence were generally thwarted. When we invited him in 2003 to speak to the philosophers at the American University in Cairo, he remarked that it was only the second time he had addressed a Department of Philosophy. I doubt that the number increased by much over the remaining nineteen years of his life.

___

Latour’s innovation –foreshadowed by his intellectual ancestor Alfred North Whitehead– is to treat all entities equally as “actors,” analyzing them in terms of the effects they have on other actors.

___

Join the conversation