For decades we have talked about the jeopardy and promise of genetic engineering without much change. The dramatic recent breakthroughs of CRISPR technology mean that we must now confront the politics and ethics of our newfound power, writes John Parrington.

Imagine if living things were as easy to modify as a computer word file. What if the genetic code of organisms could be tweaked a little here, changed a bit there, to give organisms slightly different properties, or even radically different ones? In such a world, microorganisms might be adapted to produce new types of fuel, and farm animals or plants engineered to produce leaner meat or juicier fruit, but also to withstand extremes of temperature or drought to meet the increasing demands of climate change. Medical research too would be transformed if we could easily modify the genomes of different species in order to generate mutant animals to model human disease. If genomes really could be modified like computer text, medicine itself might look very different. Instead of people having to suffer terrible diseases like cystic fibrosis or muscular dystrophy, the gene defects associated with these conditions could be corrected in the affected tissues. If tinkering with genomes were both precise and efficient, such conditions might become a thing of the past, with genetic defects corrected at the embryo stage or even earlier, in the eggs or sperm within the gonads. Of course, this could pose the question of what was considered a defect. For instance, would the availability of personalized genome information and the ability to manipulate this information lead to parents clamouring to have offspring engineered to kick a football like Cristiano Ronaldo, compose music like Mozart, or have Einstein’s scientific genius?

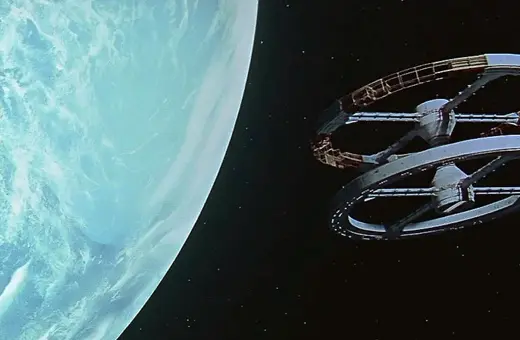

But there are other, more troubling future scenarios that can be imagined if genetic modification were to become as easy as cutting and pasting a word file. For what would stop such technology being used to engineer new lethal types of viruses, or synthetic life forms escaping and taking over the world? And how could we ensure that new types of genetically modified (GM) food – whether animal or plant – were safe to eat? Could such plants pose a risk to the environment? And what about the welfare of the modified animals? This is also potentially an issue if scientists develop new types of mutant animals to model human disease. Will this lead to pain and suffering in a wider range of species, including our biological cousins – monkeys and other primates? And if researchers developed GM primates to study how the human brain works, could this lead to a Planet of the Apes-type scenario?

Join the conversation