Following their shock split in 2021, many music fans are now left to discuss the enduring legacy of Daft Punk. The duo, defined by their robot masks and pounding electronic beats, certainly blazed a trail within the music industry. Yet few of us understand quite how their legacy transcends the realms of synthesisers and vocoders. In this article, James Tartaglia explores the metaphysics of Daft Punk, and how their work can serve to lead us down a new, idealist, understanding of the world.

As French and subversive as OCB rolling papers, Daft Punk are “widely regarded as one of the most influential acts in dance music history” (Wiki), so it was big news in 2021 when the duo announced their decision to disband after 28 years of chart-topping success. When Wiki refers to their place in “dance music history”, however, this does not include medieval bagpipe music, nor Glenn Miller, whose big band is also “widely regarded as one of the most influential acts in dance music history”. That’s because in addition to its generic meaning, “dance music” has become a label for a particular idiom – a futuristic, electronic music of which Daft Punk are the premier exponents. When it arose, and how it is to be musically demarcated, are questions never likely to be answered to much satisfaction, but I take it Black Box’s “Ride on Time” (1989) was an early and influential example. I remember finding that song particularly annoying, albeit obviously significant, when it was the new big thing.

SUGGESTED READING

Nietzsche, Dune and the power of religion

By Kevin S. Decker

SUGGESTED READING

Nietzsche, Dune and the power of religion

By Kevin S. Decker

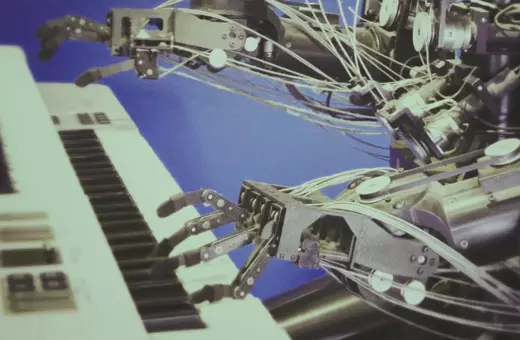

So, is there anything philosophically significant about Daft Punk? If there is you’d never guess it from the name, which, like the Average White Band, was inspired by a hostile review; the reviewer dismissed their early efforts as “daft thrashy punk”. There is philosophical resonance, however, to the fact that they dress as robots, which is a stage persona suggesting deliberate synergy between their futuristic music and either a transhumanist or posthumanist philosophy. The difference is crucial, with transhumanists hoping for a future in which humans become “Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger” (the name of a 2001 Daft Punk hit), whether by merging with machines, or through eugenics, while posthumanists hope for our replacement by robots. That Daft Punk have claimed to be robots themselves suggests an undefined territory between the two; although born human, there was apparently an explosion in their studio at 9:09AM on 9th September 1999 which turned them into robots. It is hard to confirm or disconfirm these claims because Daft Punk keep their identities concealed – even when not wearing robot helmets, they wear masks, or bags over their heads, or give interviews with their backs turned. You don’t get to look into the eyes of Thomas Bangalter and Guy-Manuel de Homem-Christo, that’s all part of the Daft Punk act. And why should that be? The formative influence of Andy Warhol, cited by Bangalter, provides a good explanation, for it was Warhol who promised a future in which international consumerism would no longer tolerate elitist high art and the cult of the genius, instead turning art over to the masses, who would each be accorded their 15 minutes of fame. Daft Punk’s robots anonymously generating electro-music for the gyrational needs of the fleshy masses are a musical fulfilment of Warhol’s vision.

___

These philosophers would, no doubt, regard Daft Punk as the crystallization of everything that’s wrong with modern culture, but the duo themselves are hardly uncritical advocates of the techno-future they envisage

___

Join the conversation