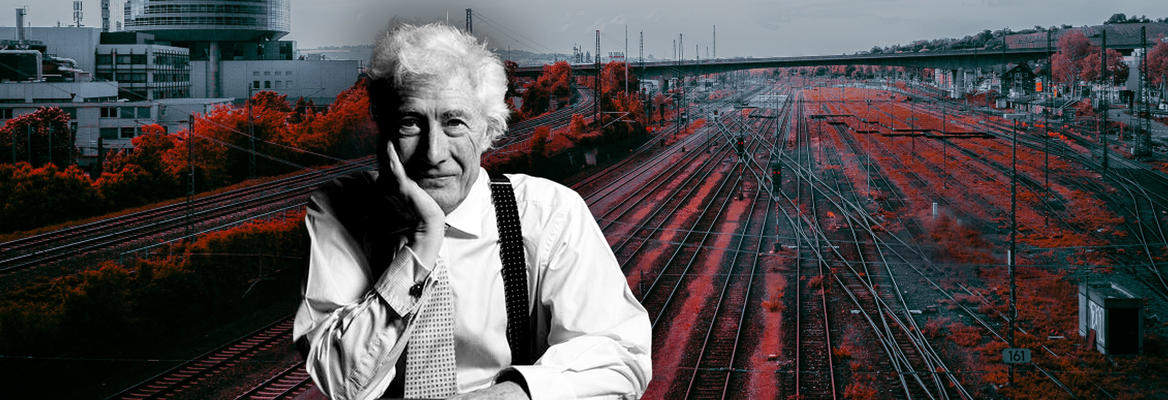

Democracy is increasingly under threat. In Britain, 94% of voters believe their views are not the main influence behind government decisions, and frighteningly similar trends seem to be emerging around the world. In this exclusive interview, former supreme court justice Lord Jonathan Sumption argues that the greatest threats to democracy are not what people usually think. He also argues that ‘long-termism’, the view popularised by Will MacAskill which suggests that policy should be orientated to the next million years, rather than just the next generation, is utterly untenable and could sow the seed for despotism.

You have said that the greatest threats to democracy are not major catastrophes, like wars, but smaller scale crises. Why?

You have major catastrophic events in the history of this country like the Second World War. Britain turned itself into a temporary dictatorship with many ordinary civil rights suspended for the duration. Now, that does not mean that Britain had become a despotism or ceased to be a democracy, because the extreme nature of the events and the temporary nature of the measures taken seem to me in most cases, to be a sufficient safeguard.

What happens, however, when you demand the protection of the state against much smaller perils? Disease, violence, financial catastrophe are all great misfortunes, but they are not of the same order as major wars. The more comprehensively you ask for the protection of the state, the more it is going to intervene by coercive measures because the coercion is the only tool that the state has got to cause people to behave in a different way. Once you start allowing the state to organize your life at an ever lower level of daily significance, you are beginning to sacrifice very much more. Because if you want to hand over to the states the power to regulate your life in trivial respects, the state is going to end up doing it all the time.

___

Once you abandon the institutional procedures that every society has for making decisions on issues that people disagree about, all you are left with is a resort to force.

___

Movements such as Extinction Rebellion or Insulate Britain would argue that the types of risks that they're alerting people to, like the climate change risk, constitute the same kind of emergency as a war, meaning they can be justified in resorting to measures that are fundamentally undemocratic. What would your response be to this?

My response would be, who is going to define what sort of events justify that kind of intervention? If they decide it’s one thing, say the climate crisis, what happens if you disagree? If you and I disagree about whether an event justifies extreme measures, how are we going to resolve that disagreement other than by force? The answer is we can't. Once you abandon the institutional procedures that every society has for making decisions on issues that people disagree about, all you are left with is a resort to force. And that's the ultimate implication of what people like Extinction Rebellion and Insulate Britain are doing. They are saying we are right, therefore you must succumb to us. And if you don't like it, we're going to make you do it.

So would you say that the difference in the kind of force that a government might use when dealing with an emergency versus extinction rebellion, is that the government has a mandate from the people to deal with emergencies whereas protest groups don’t?

Join the conversation