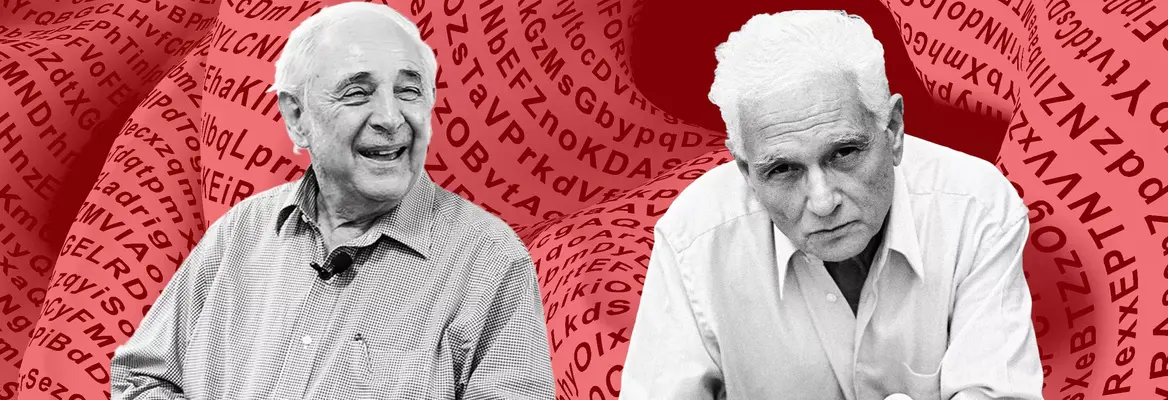

The legendary exchange between Derrida and Searle on the nature of language remains a symbol of the chasm between the so-called Analytic and Continental traditions of philosophy. But beyond highlighting the blind spots of an understanding of language that excludes literature, irony, jokes, and the subconscious, the exchange also underlines the refusal of analytic philosophers to seriously engage with the other side, writes Peter Salmon.

"With Derrida, you can hardly misread him, because he’s so obscure. Every time you say, 'He says so and so,' he always says, 'You misunderstood me.' But if you try to figure out the correct interpretation, then that’s not so easy."

- John Searle

Jacques Derrida was and is one of the most controversial philosophers of all time. To many, particularly in the ‘analytic’ tradition of philosophy, he remains a charlatan. To others, those in the ‘continental’ tradition, he is one of the greatest thinkers of the twentieth century, whose insights, on language in particular, are both deeply thought out and represent a deep shift in the way we think about not only philosophy but literature, film, politics, even identity.

That the terms ‘analytic’ and ‘continental’ even exist is, in some ways, to operate as a bulwark by British analytical philosophers against the ‘nonsense’ coming from ‘over there’ – predominantly France. In reality, the analytic tradition, as thinkers like Christoph Schuringa have pointed out, only becomes dominant in the mid-twentieth century, while ‘continental’ philosophy is an exonym – no French thinker would describe themselves as ‘continental’. In fact, Derrida called ‘his lot’ traditional philosophers, dealing as they did with things like love, death, ethics and literature, rather than the narrow field of logic.

___

Derrida was an admirer of Austin, and felt that he had made a fundamental breakthrough by calling into question a view of language that argues the only true sentences are those that ‘correspond’ in some way to reality.

___

This argument rumbles on, despite the efforts of philosophers such as Richard Rorty and Brian Leiter to bridge the divide. Some of the battles have become legendary, perhaps none more so than the dispute between Derrida and the American philosopher John Searle. Nearly fifty years on, it is the foremost example of the confrontation between the two schools, even if both philosophers refused to see it as such.

Derrida and the limits of what J.L. Austin could do with words

In 1977, Derrida’s 1972 essay ‘Signature Event Context’ appeared in English for the first time. It is one of his most challenging texts, and begins with a provocative question. ‘Is it certain that the word communication corresponds a concept that is unique, univocal, rigorously controllable, and transmittable: in a word, communicable?’ That is, does language, when spoken between people, act in the way that had become one of the shibboleths of analytic philosophy – with clarity and precision.

In his sights was the late philosopher J. L. Austin, whose How to Do Things With Words had become a key text in the philosophy of language. Derrida was an admirer of Austin, and felt that he had made a fundamental breakthrough by calling into question a view of language that argues the only true sentences are those that ‘correspond’ in some way to reality.

SUGGESTED READING

Searle vs Lawson: After the End of Truth

By Head to Head

SUGGESTED READING

Searle vs Lawson: After the End of Truth

By Head to Head

Join the conversation