The #MeToo movement has exposed a number of men in Hollywood as sexual predators. Starting with Harvey Weinstein and Kevin Spacey, #MeToo’s momentum kept going, with comments sections in scores of articles worrying about the next shoe to drop; many wondered whether one of their favorite actors or directors would be next. By and large, it has been a good, if painful, process, and the worries about “witch hunts” are unfounded. But #MeToo has forced many of us into an uncomfortable position. What do you do with all those movies you like, when they’re made by someone you know to be a monster?

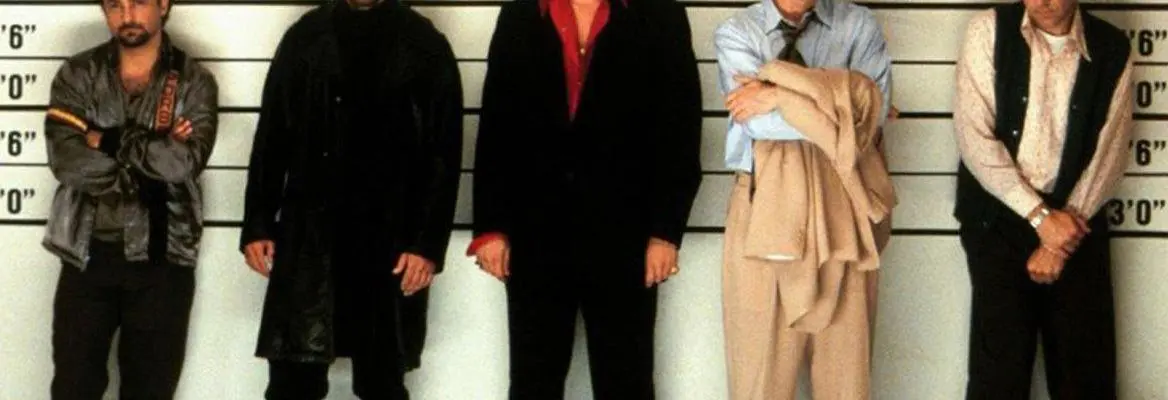

Take the The Usual Suspects, directed by Bryan Singer (who had dubious relationships with younger men) and starring Kevin Spacey in an iconic role. What do we do with The Usual Suspects, knowing what we know now? There are two ways to understand this question, first as a moral question, and second as a practical one. In a moral mode, the question is: what would be the ethical thing to do with movies made by vicious people, knowing what we know now? The practical version asks: what should I do with these movies, in light of what I know now? Many prioritize the moral question (see the post on #MeToo at Daily Nous); once you answer it, an answer to the practical question follows naturally. But I think the practical question could just as well come first, and indeed, I think that it actually does occur to us before the moral question. An uncomfortable feeling follows from knowing that one has enjoyed the work of a vicious person. I’ll call this the “grossness” phenomenon: it makes us uneasy to enjoy the work of a monster. But why does the grossness phenomenon arise at all?

___

"The connection between enjoyment and credit to the creator might have exceptions, but it explains the asymmetry in our reactions to learning that an artist we like is a fiend, and learning that an artist we hate is a fiend. The latter doesn’t change our attitudes to the works in question, but the former does."

___

I say “enjoy” rather than merely “consume,” because the phenomenon only seems to follow from enjoyment. If I consider Brett Ratner to be a hack, then learning that he’s a serial harasser won’t make me feel gross about my past consumption of his work. Not so for The Usual Suspects; since I like that movie, I might regret my past enjoyment, and forswear future viewings. “Consumption” also implies payment, which is also irrelevant to grossness. I might pass on watching “The Usual Suspects,” even if I could do so for free, without any royalty checks going to Singer.

One explanation for grossness says that the feeling comes from the intuition that it’s morally wrong to enjoy the work of a vicious artist. Our moral intuitions come first, and they infect our enjoyment of movies. This isn’t obviously true, though. Imagine you were satisfied by an argument that viewing movies by monsters is morally neutral; if you stumble upon a Usual Suspects DVD on the street and watch it in the privacy of your home, there’s no harm and no foul. But for many of us, the supposed moral neutrality of viewing might not matter. We would still feel gross, even as we’re convinced that we aren’t wronging anyone.

Join the conversation