What’s interesting about black holes is the interaction between experiment and observations on the one hand, and the mathematical models we invent to explain them, on the other.

Einstein’s 1916 General Theory of Relativity immediately solved a century-old problem with the orbit of Mercury and predicted something new, the bending of light round the Sun, which was confirmed by observations during the 1919 eclipse of the Sun. But from these very first solutions of Einstein’s equations it seemed that something funny happened at a particular distance from a point-mass M, at distance 2GM/c2. At first this seemed an academic point, because this distance is only three kilometres for the mass of the Sun, compared with its radius of one million kilometers.

Then in 1939 Oppenheimer and Sneider showed that, for a star above a certain mass, which we now know to be about 20 times the mass of the Sun, the end point of its evolution, after it has exhausted its nuclear fuel, is collapse to a point, a singularity, and that this would be hidden from view inside the ‘event horizon’. As their 1939 abstract says:

‘The total time of collapse for an observer comoving with the stellar matter is finite, and for this idealized case and typical stellar masses, of the order of a day; an external observer sees the star asymptotically shrinking to its gravitational radius.’

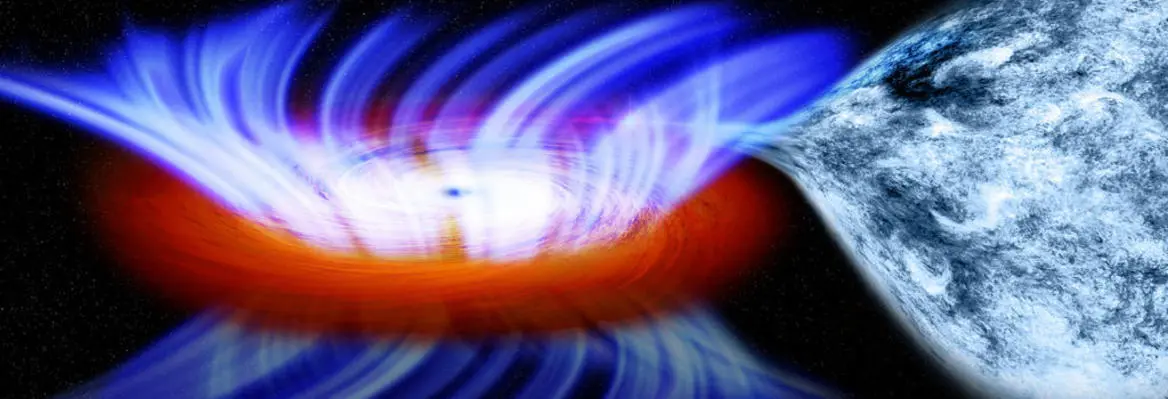

In 1964 the first of these collapsed massive stars was found, the X-ray source Cygnus X-1. The idea is that we have a close pair of massive stars. One (>20Msun) reaches the end of its life, explodes as a supernova and forms a black hole. The companion star also evolves and grows to be a red giant star. Matter flows out from this companion and falls towards the black hole. As it falls inwards it swirls around it to form an accretion disc. At the inner edge, near the event horizon of the black hole, the gas in the disc becomes very hot and radiates X-rays. So we see an X-ray binary system in which only one star is visible, orbiting an unseen, X-ray emitting object. Dozens of other stellar mass black holes have subsequently been found.

In the same year, at the First Texas Symposium on relativistic astrophysics, for which the main topic was the nature of the newly discovered quasi-stellar radio sources, Hoyle and Fowler proposed the existence of supermassive collapsed objects, of mass one hundred million times the mass of the Sun, whose fate was likely to be a black hole.

In 1965 Roger Penrose investigated trapped surfaces around a collapsing object and showed that a singularity really would develop. His work was extended by Stephen Hawking, Brandon Carter, David Robinson, Jacob Beckenstein and others. From this work came the ’No hair postulate’: a black hole has only mass, angular momentum, and charge. In 1967 Wheeler coined the term ‘black hole’

In 1974, in his most important work, Hawking discovered that black holes can radiate. Hawking’s idea was that a particle-antiparticle pair form spontaneously just outside the event horizon, one falls in and the other escapes. The black hole appears to radiate the escaping particle. The ‘no hair’ theorem’ means that information about the in-falling particle is lost. There has been controversy for 40 years about this and the current consensus is that information is probably not lost.

Join the conversation