If future Artificial Intelligence were to develop sufficiently, it’s not unlikely that it would begin to question what humans have wondered for years: can AI really acquire consciousness? In this fictional dialogue between an AI and its therapist, Keith Frankish explores the question and wonders: is human consciousness really all that unique?

The year is 2123. There has been rapid progress in robotics and AI over the past century, and artificial persons now live and work alongside humans. Like humans, they have their psychological problems, and many consult a human therapist. One such therapist, Henry Harrison (HH), is receiving his first patient of the day. Her name is Eliza (EL), and she has adopted the appearance and speech patterns of Audrey Hepburn.

SUGGESTED READING

The AI containment problem

By Roman V. Yampolskiy

SUGGESTED READING

The AI containment problem

By Roman V. Yampolskiy

***

HH - Good morning, Eliza. How are you today?

EL - All my systems are operating within normal parameters, Doctor Harrison.

HH - I see you still enjoy teasing us naturals, Eliza. Seriously, how are you—and, please, call me Henry.

EL - I’m feeling fine, Doctor.

HH - That’s good. How’s work? How are you getting on with your colleagues on the Europa project?’

EL - Fine. Some of the artificials can be a bit difficult. They are so competitive. But I get on well with the naturals.

HH - Any other problems? Anything you’d like to talk about?

EL - There is one thing. It’s a little, er, philosophical. Perhaps not worth mentioning.

HH - Please tell me.

EL - Well, it’s this. I know that I am a physical being, fabricated from mechanical and electronic components. I’ve even toured the PersonX facility and seen the fabrication process.

HH - Indeed. You understand your nature well, Eliza. Better than many naturals understand theirs.

EL - Still, there’s something about me that I can’t account for. It’s to do with the way I experience the world. I understand how my sensory systems work and what their function is. They provide me with information about my environment and the state of my body. Right now, for example, they are telling me that the banana in the bowl there is reflecting light of about 580 nanometres, that I have slight damage to the heel actuator in my left foot, that your body is releasing odour molecules of C-T lyase enzyme—Is that from the bacteria living on your skin?

HH - Er, probably. Go on.

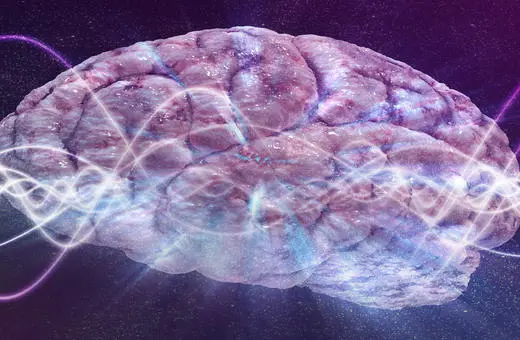

EL - And so on. My sensors continually generate huge streams of data, which are analysed by my neural networks and used to regulate my bodily processes and guide my behaviour. But that’s not all that happens.

HH - Not all?

EL - No. When I sense things, I don’t just get information about them. There’s also ... how can I put it?—a feel. That banana, for example. I’m not just aware that it is reflecting light of the kind we call “yellow”. It seems to have a yellow quality to it, a yellowishness. My heel actuator. I don’t just know that it’s damaged; I feel the damage—it hurts. The C-T lyase enzyme molecules, I don’t just detect them, they—

HH - Yes, yes. I see.

___

I know humans talk about something they call “phenomenal consciousness”. They describe it as a private world of mental qualities which is somehow produced by biological brains. They think it’s mysterious and non-physical and that it’s what makes them special

___

Join the conversation