We are told by the media that state violence and terrorism are fundamentally different. States kill civilians, but such killing is described as collateral damage – a by-product of good intentions and pursuing legitimate objectives. In this article, Oliver Adelson argues that we should collapse the distinction between state violence against civilians and terrorism, rejecting both forms of violence as illegitimate means to achieve political ends.

In his pamphlet 'The Civil War in France', Karl Marx addressed charges of barbarism levelled at the Paris Commune for its execution of hostages. Pointing to the Prussian practice of taking innocent men hostage ‘to answer for the acts of others’ and the bourgeois army’s re-establishment of the long-abandoned custom of shooting defenceless prisoners in 1848, Marx arrived at the following conclusion:

All the chorus of calumny, which the Party of Order never fail, in their orgies of blood, to raise against their victims, only proves that the bourgeois of our days considers himself the legitimate successor of the baron of old, who thought every weapon in his own hand fair against the plebeian, while in the hands of the plebeian a weapon of any kind constituted in itself a crime.

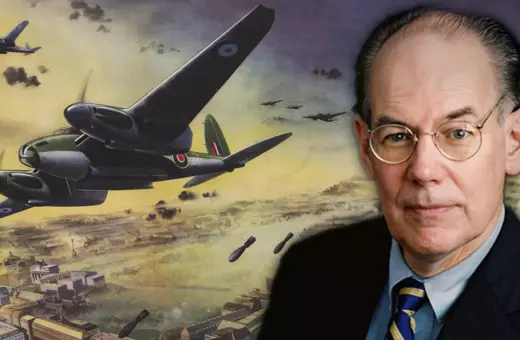

We still hear the chorus of calumny over 150 years later. When non-state actors target civilians to achieve their objectives, they are rightly condemned as terrorists, but when states like America and Israel bomb densely populated civilian areas for political purposes the resulting deaths are ‘collateral damage'. This sort of reflexive labelling has become so pervasive that it is fairly easy to predict how the Western media and political élite will characterise a group which uses violence for political ends – if the group is an ally of the US, it is fighting for freedom; if it is an enemy of the US, it is engaged in terrorism and stone-age barbarism.

The more sophisticated apologists for state violence will often draw on their philosophical reserves to justify this distinction. The most common line of defence is that while terrorists intend to harm innocent men, women, and children to achieve their political aims, states which inflict collateral damage on civilian populations only do so as an inevitable side-effect of their wholly justified objectives. Thus, if we drop a 2,000-pound bomb where we know hundreds of civilians are seeking shelter, it is justified – or at least somehow less objectionable – if the bomb also kills a high-ranking terrorist. In fact, it is often conceded that whether or not we achieve the objective is really beside the point. If we drop the bomb with the intention of killing the terrorist, this mental state is itself enough to exculpate us – in part if not entirely – of any wrongdoing.

___

There are good reasons for resisting such a sharp distinction between state violence against civilians and terrorism.

___

There are good reasons, however, for resisting such a sharp distinction between state violence against civilians and terrorism. This is not to say that both are desirable or in any way acceptable. Non-state actors which commit violence see the implication 'if state violence is morally unobjectionable, then terrorism is morally unobjectionable' and take it as encouragement, when we should really take it as a sign that, since terrorism is clearly wrong, we have a responsibility to restrain states from committing violence.

Join the conversation