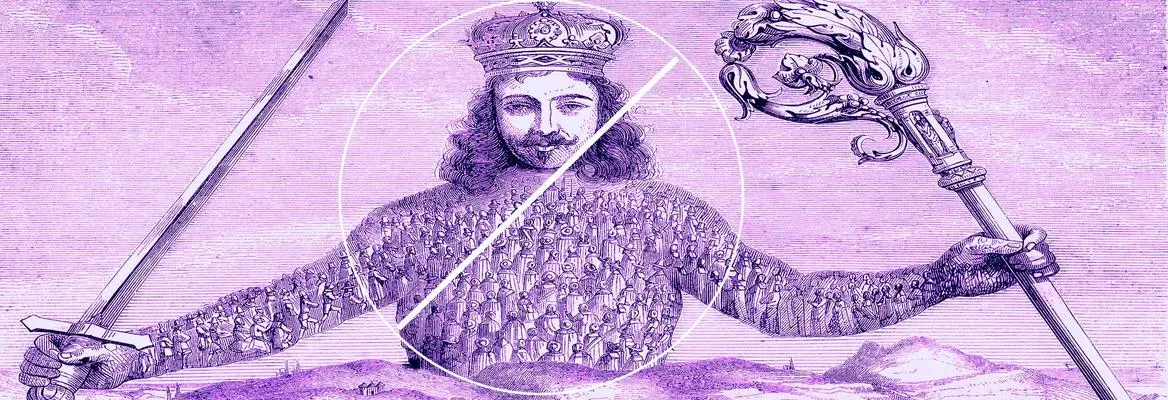

The idea that society is ordered from the top-down originated from Thomas Hobbes’ seminal 1651 book, Leviathan. And this idea still resonates strongly today: we agree to a social contract in which we give up some of our freedoms to the state, in the hope that it will ensure order and our protection. Yet here, Gary A. Fine discusses why Hobbes was mistaken to think that order must be built vertically, and instead asserts that we should look to our local groups and communities to order society, and drive us towards a more just world.

Edmund Burke, the profound English political theorist, noted in his Reflections on the French Revolution:

"To love the little platoon we belong to in society is the first principle of public affections. It is the first link in the series by which we proceed towards a love to our country, and to mankind."

Revolutions, democratic transitions, or conspiracies by shadowy elites all have their basis in little platoons. If we examine the genesis of the First World War, the French Revolution, the Civil Rights movement, or the stable governance of a small farming town, we find a set of tiny publics, perhaps working together or engaged in conflict, that create the basis for political action. Change is possible because of joint political projects.

A shared politics, so crucial in democratic theory, exists because friends can choose to merge their interests and their costs. Governments, communities, and institutions build on the activity of their tiny publics. People see the world in much the same way as their close associates, whether or not they hope for the same future. We do not live with millions, but with a few, and they influence how we see the world.

How social relations shape our views and attitudes

The American pragmatist philosopher John Dewey famously claimed in The Public and Its Problems that “the intimate and familiar propinquity group is not a social unity within an inclusive whole. It is, for almost all purposes, society itself.” Dewey argued that local relations constitute society. For Dewey, in democracy the ear is more powerful than the eye. Personal connections trumps what any individual can perceive. As Dewey tells us, “Vision is a spectator; hearing is a participator.” Few individuals comply with moral demands out of pure conscience, absent of the support of colleagues.

The presence of what is variously known as group cultures, micro-cultures, or idiocultures reveals how interactions and institutions operate through the common recognition and intersubjective experience of participants, but this depends on shared action. It is by recognizing the importance of performance in everyday life that Erving Goffman speaks of the “interaction order.” Goffman writes that

At the very center of interaction life is the cognitive relation we have with those present before us, without which relationship our activity, behavioral and verbal, could not be meaningfully organized.

We act together because we think together, and we think together because we act together. By participating in this interaction order, group members treat their association as stable, ongoing, and influential. Further, this stability depends on memory as based in ongoing connections. Culture is not merely cognitive but is revealed in action.

Goffman argued that we build society through a tacit agreement to create order because we use past interaction as a model for the present. As a result, the establishment of comforting interactional routines generates trust, and this trust can apply personally or through institutions. The interaction order allows us to embrace social organizations from the dyad to the globe and from the bedroom to the state.

Join the conversation