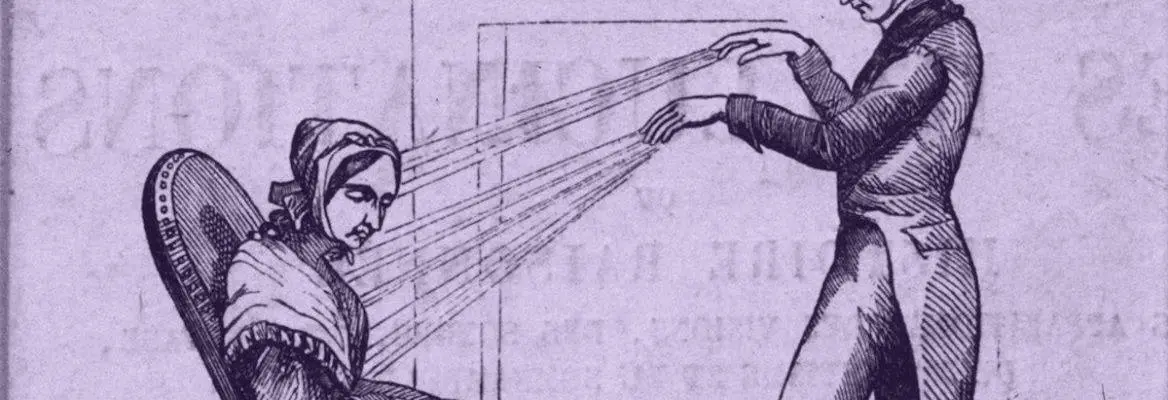

In 1778, the practice of animal magnetism started in Paris. Magnetists enjoyed six happy years; then a star-studded panel of mostly French academicians declared, as John Adams put it, that their science did not exist. Late in 1784, the American Herald published a letter from Adams, then in France, to his friend the physician Benjamin Waterhouse, then in Boston. The letter contained the first mention in the American press of both animal magnetism and its debunking at the hands of the French academicians. The Austrian physician Franz Anton Mesmer had been making a success de scandale in Paris by claiming to cure illnesses with the invisible fluid of “animal magnetism” (magnétisme animal), a living analog to mineral magnetism that was distributed throughout the cosmos and was especially active in human bodies. (“Animal” is something of a misnomer; Mesmer meant animal as opposed to mineral, not as opposed to human. Think “vital magnetism.”) Adams aptly called Mesmer’s practice “a kind of physical new light or witchcraft.” It mixed Bavarian exorcism, a practice Mesmer had claimed to explain with his own principles, with a view of matter that seemed vaguely drawn from Benjamin Franklin’s Experiments and Observations on Electricity (1751). According to Mesmer, imbalances in the magnetic fluid were at the root of all disease. By manipulating the fluid through gestures called the “magnetic passes,” he could make his patients seize, shriek, go into hysterics, vomit, and, allegedly, get well. The theory was that magnetization cleared obstructions in the movement of the body’s vital fluids. But Adams and other Anglophone observers were put more in mind of new-light Protestant convulsions in the Great Awakening. The prodigies of animal magnetism took place in Mesmer’s very public treatment salons, where the mise-en-scène showed the Austrian’s flair for theater. The walls were padded and decorated with celestial symbols, the air vibrated with glass harmonica music, and the doctor wore purple—flowing violet robes, to be exact. Some of the patients’ fits bore a suspicious resemblance to orgasm.

How The Occult Thrived in an Age of Enlightenment

As the case of mesmerism showed, fighting fakery with facts is no match for the imagination

12th March 2019

Continue reading

Enjoy unlimited access to the world's leading thinkers.

Start by exploring our subscription options or joining our mailing list today.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Latest Releases

Jennifer Garcia 21 February 2020

Age of enlightenment was too obligatory and it showed a lot of changes for all the people. Thus, you have to present [url=https://customessaysreviews.com/college-paper-org-review/]college paper review[/url] that will have all the literature about the age and inform more.

Join the conversation