We normally think of words as a tool for describing the world around us. A helpful shorthand or label for expressing meaning. But words have power. The way we describe things affects how we see them. And crucially, words, by directing attention, can act as off-switches for the mind, limiting a broader understanding of a situation, argues Nick Enfield.

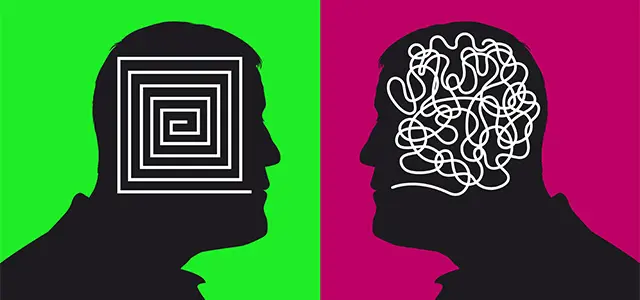

How I see an image is a private matter. But how I label it is an imposition upon others. Think about this when you are next in an art gallery. The plaque next to each exhibit contains words that constrain how you view the exhibit. Inversions and reversals are familiar from the abstract imagery of Gestalt Psychology. We all know the trophy-faces image:

If the above image were labelled “Faces,” this wouldn’t mean that the trophy couldn't be seen. But it would mean that somebody with authority—the artist, in this case—has claimed one of the available construals as the correct one.

___

Even when you have no interest in misleading people, as with the trophy-faces image, you have no choice but to pick one way of seeing things at a time.

___

This is linguistic framing. It is one of the things that language is especially good for. Framing is not just a different way of viewing a scene. It is an act of influence. It uses language to direct people to see things in one way as opposed to the other ways they might have seen them. This tends to shut off our awareness of those other ways of seeing. Framing can be used intentionally to distract from other available frames. But even when you have no interest in misleading people, as with the trophy-faces image, you have no choice but to pick one way of seeing things at a time.

Framing can reveal our moral evaluation of a situation. If I say Kim is thrifty, I’m saying two things: (1) she doesn’t spend much money and (2) that’s a good thing. An alternative framing would be that she is stingy. This would also describe a person who doesn’t spend much money but the framing is negative.

Framing’s special power is to direct our attention. It is hard to imagine a more important way of manipulating people. I only have to look and point my finger in a certain direction and you will be unable to resist looking to see what’s there. That’s when I pick your pocket. As magicians, marketing gurus, and schoolmasters have long known, controlling people’s attention is key to influencing them.

SUGGESTED VIEWING Lost in language With Rufus Duits, Hilary Lawson, Barry C. Smith, Maria Balaska

Consider this example: I’m not his daughter, he’s my father. Two descriptions of a situation are both true: (1) I’m his daughter, (2) He’s my father. But we can understand what the speaker is doing when she insists on one version. She wants the father defined in relation to her. The framing makes a claim that people should know who she is before they know who the father is.

Alternative framings are not a superficial matter of emphasis or style. Framing affects how we understand and reason. A study of blame, by Caitlin Fausey and Lera Boroditsky, presented people with a vignette about a diner in a restaurant who accidently starts a fire by snagging the tablecloth and toppling a candle. When the text frames the diner in subject position (She toppled the candle; as opposed to The candle toppled), this affects the degree to which people judge her as responsible and accountable for the damage.

___

Join the conversation