In Jonathan Coe’s 1992 anti-Thatcherite satire, What a Carve Up!, the Tory tabloid journalist Hilary Winshaw publishes a novel that boasts ‘Sex every forty pages’. By the standards set by EL James twenty years later, that is paltry. Ever since the 1960s, British publishers have been pressurising their authors to write sex in order to boost sales, presumably following the success of the novel that inaugurated that decade, the unexpurgated Lady Chatterley’s Lover. By 1993, the British literary magazine Literary Review felt the need to create the ‘Bad Sex Awards’ in order ‘to draw attention to the crude, tasteless, often perfunctory use of redundant passages of sexual description in the modern novel, and to discourage it.’ Winners have included Melvyn Bragg (1993), Sebastian Faulks (1998), Tom Wolfe (2004), Norman Mailer (2007), Ben Okri (2014), and, most recently, James Frey in 2018.

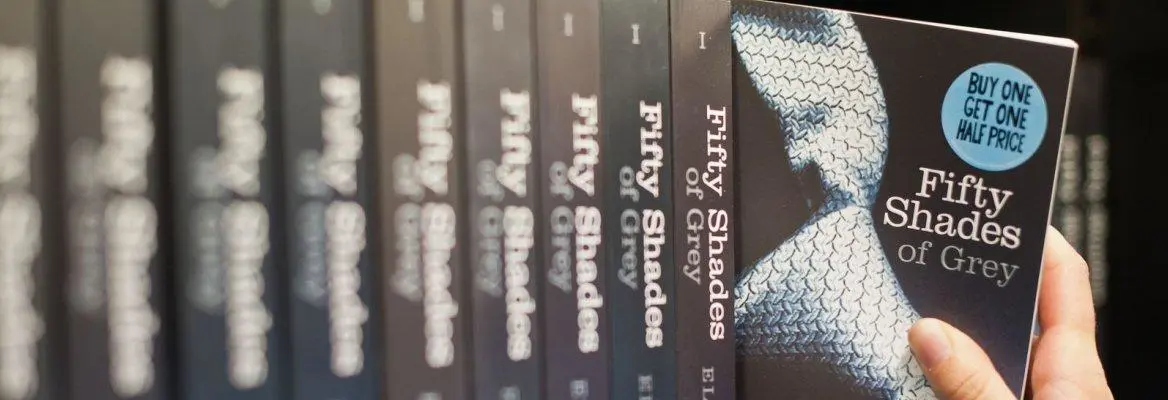

At the risk of taking too-seriously an award of which the keynote is not seriousness, there are several problems involved in this that are worth considering. One is the implicit hypocrisy that the award has brought great publicity to its parent magazine because of the very fact – which the award ostensibly disparages – that sex sells. Indeed especially badly-written sex sells, hence the success of the Fifty Shades trilogy (‘I detonate around him, again and again, round and round, screaming loudly as my orgasm rips me apart, scorching through me like a wildfire, consuming everything.’ [Fifty Shades Freed]).

Then there is the fact that – since individuals’ sexual experiences are nothing if not mutually varied - one person’s literary bad sex may be another’s actually-quite-moving sex. The format of the awards ceremony itself – in which actors read out the short-listed passages, to reliable laughter from their audience – militates against any other reaction than ridicule. Yet I have on several occasions at these ceremonies found myself laughing with my face only.

Then there is the ambiguity of the adjective. What is meant by ‘bad’, we infer, is ‘aesthetically poor’. But it is striking that ‘bad sex’ – in the sense of the spectrum that covers disengaged sex, through unenjoyable sex, to coercive sex and rape – is relatively little featured in the shortlists. A scene containing rape is, by a common delicacy in the use of language, less likely to be described as a ‘sex scene’ than as a ‘rape scene’; therefore ‘bad sex’, as far as the awards are concerned, often means ‘rather good sex’. Pornography - in the sense of literature in which sex predominates - is formally excluded from the awards, but it is also marginalised from them in the sense in which D.H. Lawrence redefined the term in his 1926 essay ‘Pornography and Obscenity’: ‘even I would censor genuine pornography, rigorously […] you can recognize it by the insult it offers, invariably, to sex, and to the human spirit. Pornography is the attempt to insult sex, to do dirt on it. This is unpardonable.’

___

"Alienation – which is not sex itself – rescues such passages from ridicule. This points to the fact that the Bad Sex Awards have what is intrinsically an easy target. Looked at from the outside, the physical actions of sex, and mental concentration involved in them, often seem absurd"

___

Join the conversation