In his new book, When Maps Become the World, University of California, Santa Cruz philosopher and humanist Rasmus Grønfeldt Winther shows how the scientific theories, models and concepts we use to intervene in the world function as maps. We increasingly understand the world around us in terms of models, to the extent that we often take the models for reality. Winther explains how our representations in science become dominant social narratives—they become reality, and they can remake the world.

This extract is taken from Chapter 9: Map Thinking Science and Philosophy

How do we understand the reality of the objects and processes postulated by science? Did Galen’s four humors exist in some sense, despite the fact they were disproven? Were atoms or electrons or genes ever not real? Do social classes or the unconscious exist, and in what sense? What role do researchers or the lay public or university science students play, if any, in establishing and stabilizing the existence and reality of such objects and processes?

Differing intuitions regarding what exists are deeply rooted in the philosophical traditions of diverse cultures. Do you or I exist, or are we a dream, an emergence, a fabrication? Are we and our thoughts an integral and essential part of reality, or does reality exist separately, whether as pure matter, or with its own soul(s), logic(s), or god(s)? If the apparatuses of human thought and sensation are indeed cleaved from reality, then is reality hidden behind a translucent— or, worse, opaque — veil of appearance? Are you and I free in our will and in our actions, and can our aspirations, imaginations, and activities significantly affect the world? Our attitude toward these questions impacts what we believe and imagine we can change with our knowledge and actions; how we imagine our role and place in the universe, and in society; and which sorts of futures we might consider possible and desirable.

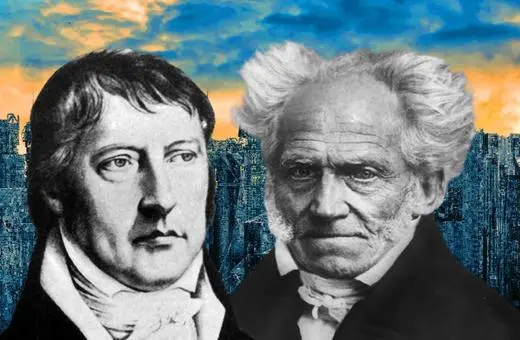

Philosophers and other thinkers and doers have delved extensively into such questions and concerns. Consider three families of philosophical approach to questions about what exists, and how and why:

• Constructivism highlights the roles that humans play in co- determining the world via scientific interventions and representations.

• Empiricism is concerned with how inferences can be legitimately drawn from data, measurement, and observation.

• Realism interprets scientific theories as mirrors of a nature independent of human will, mind, and sense, and it interprets the theories as becoming increasingly certain and proven over history, through ongoing correction of error.

Drawing on the map analogy, each of these positions can be likened to a philosophical projection onto the actual, in vivo representational practices of science. Each of the three projections yearns for completeness, in the style of Mercator’s projection, and philosophically universalizes itself. Each comes with attendant fears, and asserts itself in dialectical opposition to the others. Each has a key cartographic counterpart, and each will be illustrated, briefly, with the question of the existence of genes.

The Mercator Projection became the standard map projection for navigation because of its unique property of representing any course of constant bearing as a straight segment. It inflates the size of objects away from the equator.

Join the conversation