We are more conscious than ever of the harms of misinformation for the common good. This concern is driven by a widespread understanding of misinformation as a public disease in need of an urgent cure. Against this picture, philosopher Daniel Williams argues that misinformation is often a symptom of a deeper public malaise -- and that debunking and censorship won't be the magic bullet that we're hoping for.

Since the United Kingdom’s Brexit vote and the election of Donald Trump in 2016, we have been living through an unprecedented societal panic about misinformation. Poll after poll demonstrates that the general public is highly fearful of fake news and misleading content, a concern which is widely shared among academics, journalists, and policymakers.

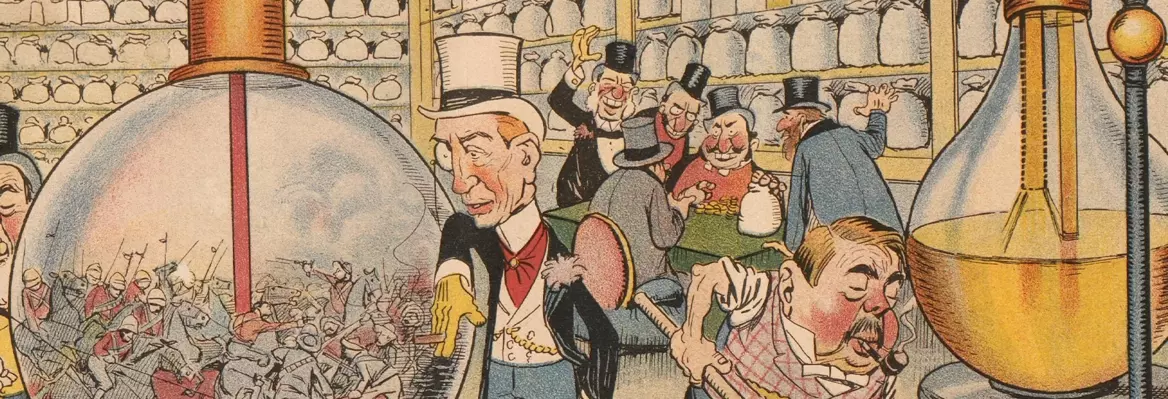

This panic is driven by the narrative that misinformation is a kind of societal disease. Sometimes this metaphor is explicit, as with the World Health Organisation’s claim that we are living through an “infodemic” and influential research that likens misinformation to a contagious virus, but it also motivates the common diagnosis that misinformation lies at the root of many societal ills. In this analysis, ordinary individuals are routinely sucked into online rabbit holes that transform them into rabid conspiracy theorists, and misinformation is the driving force behind everything from vaccine scepticism to support for right-wing demagogues.

___

If misinformation is a societal disease, it should be possible to cure societies of various problems by eradicating it.

___

The disease model of misinformation has practical consequences. If misinformation is a societal disease, it should be possible to cure societies of various problems by eradicating it. The result is intense efforts among policymakers and companies to censor misinformation and reduce its visibility, as well as numerous initiatives that aim to cure citizens of false beliefs and reduce their “susceptibility” to them.

Is the disease narrative correct? In some cases, exposure to misinformation manifestly does have harmful consequences. Powerful individuals and interest groups often propagate false and misleading messages, and such efforts are sometimes partly successful. Moreover, evidence consistently shows that the highly biased reporting of influential partisan outlets such as Fox News has a real-world impact.

Nevertheless, the model of misinformation as a societal disease often gets things backwards. In many cases, false or misleading information is better viewed as a symptom of societal pathologies such as institutional distrust, political sectarianism, and anti-establishment worldviews. When that is true, censorship and other interventions designed to debunk or prebunk misinformation are unlikely to be very effective and might even exacerbate the problems they aim to address.

To begin with, the central intuition driving the modern misinformation panic is that people—specifically other people—are gullible and hence easily infected by bad ideas. This intuition is wrong. A large body of scientific research demonstrates that people possess sophisticated cognitive mechanisms of epistemic vigilance with which they evaluate information.

___

If people are not gullible and persuasion is difficult, what explains the prevalence of extraordinary popular delusions and bizarre conspiracy theories?

___

If anything, these mechanisms make people pig-headed, not credulous, predisposing them to reject information at odds with their pre-existing beliefs. Undervaluing other people’s opinions, they cling to their own perspective on the world and often dismiss the claims advanced by others. Persuasion is therefore extremely difficult and even intense propaganda campaigns and advertising efforts routinely have minimal effects.

Join the conversation