Nietzsche has been held up as the arch-philosopher of an aristocratic politics. Nietzsche claimed a lineage with Plato and his theory of an authoritarian state. Donovan Miyasaki disagrees, arguing Nietzsche fails to follow the platonic model. Nietzsche and Plato both placed their ideas of the state as reflections on the souls of individuals. Nietzsche’s’ theory of a state is based on the idea of a manifold soul, leading to a society which cultivates harmony and freedom.

I’d like to contrast Plato’s picture of the self or soul to Nietzsche’s account of what he calls a “manifold” soul. While Plato’s moral ideal is a rigidly hierarchical soul subordinated to reason, Nietzsche’s manifold soul is a dynamic balance of powers, a contentious unity of diverse personas. And although Plato’s just soul serves as the model of his authoritarian, aristocratic politics, Nietzsche’s manifold soul is deeply incompatible with his aristocratic politics. This provides us, very much against his intentions, with the foundation for a novel theory of egalitarian social harmony.

In The Republic, Plato compares the moral perfection of individuals and society to musical harmony: a just individual or city is a beautiful unity of distinct elements and voices. Of course, most of us live in a state of disharmony: our soul is an orchestra that is out of time and out of tune, producing cacophony rather than music. Although moral improvement requires bringing the three parts of our souls into an agreement, the perfected self is not a community of equals. Instead, Plato compares the just soul to a chariot driver guiding a horse or a farmer tending animals. Reason is the authority over and caretaker of our emotions and appetites, constraining their recklessness and guiding them with knowledge of their true good.

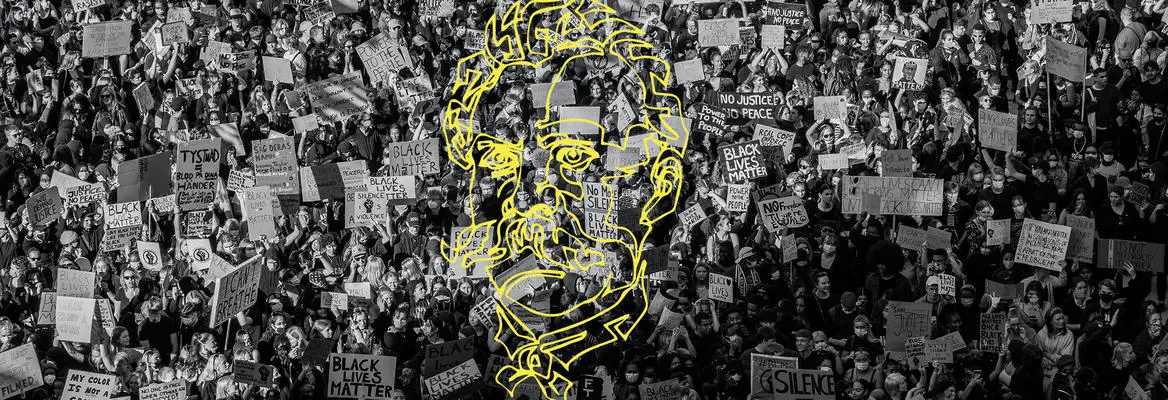

___

Our soul is an orchestra which is out of time and out of tune, producing cacophony rather than music.

___

This picture of the soul in turn serves as Plato’s model of the ideal city. A social order has three elements corresponding to the parts of the soul: wise “guardians” create just laws, a “warrior” class protects the laws from internal and external enemies, and a “producer” class creates the goods necessary for society’s material prosperity. Just as emotions and appetites should be governed entirely by reason, only the guardian class should have political power. For Plato, we can make beautiful music together only through an aristocratic social order, the political subordination of the majority to a small group of (hopefully, if improbably!) wise rulers.

This might seem contradictory: how can harmony consist of such a radical imbalance of powers? True, an orchestra requires a leader to play well. But surely an orchestra in which everyone is entirely obedient to a single individual, showing no individual spontaneity and making any creative contribution, cannot produce great music?

But this objection overlooks Plato’s secret: he doesn’t believe the soul has three parts after all. In reality, the soul is singular, for the mind survives the death of the body. Our emotions and appetites are just accidents of our attachment to a body, not part of our real selves. They don’t play an equal role in governance because they are not separate agencies but mere instruments of reason.

Join the conversation