There is a great divide running through philosophy. Analytic versus Continental. The proponents of each see their version of philosophy as more valid and cast doubt on the legitimacy of the other. Philosopher Simone Mahrenholz here argues this divide is the product of contingent events in history. Tracing the origins of both schools in part to outstanding personalities in early 20th-century Germany and Europe, in conjunction with world-political developments, she reveals this rift in philosophy as caused and radicalized by a peculiar course of events, including the rise of Hitler.

Newcomers to contemporary academic philosophy might find themselves at times perplexed by the degree and vehemence with which the discipline is still divided at most philosophy departments in the world. The current distinction between so called “analytic” and “continental” philosophy is at the latest a product of the 1970s, its methodological foundations however, have their origin in the 1920s or earlier. And, strictly speaking, it is a false equivalent: relating a method, analytic, to a region, the European continent. One could talk instead of Anglo-American versus European philosophy, or of analytic versus historical methods. But both of these would be misleading. Authors subsumed under “continental” are not predominantly historical in orientation, yet they include historical investigations for inquiries into their fields. “Analytic” philosophers, in contrast, tend to dismiss discourses from previous centuries as overcome by – well – scientific progress. They self-identify via the ideals of exactness and clarity and the method of logical analysis: of concepts, arguments, language and their relation to reality. Also, hardly any conference call or job posting goes out without explicit reference to methodological “rigour”.

What method, then, complements “analytic” on the continental side? This depends partly on whom you ask. The large, heterogeneous group under this umbrella includes German idealism, phenomenology, existentialism, critical theory, (post-)structuralism, as well as their predecessors, such as Kierkegaard, Nietzsche and many others. We often find a tendency here to engage in meta-philosophical self-reflection, alongside an awareness of the historical emergence of those concepts, actions and values that seem to be naturally given.

___

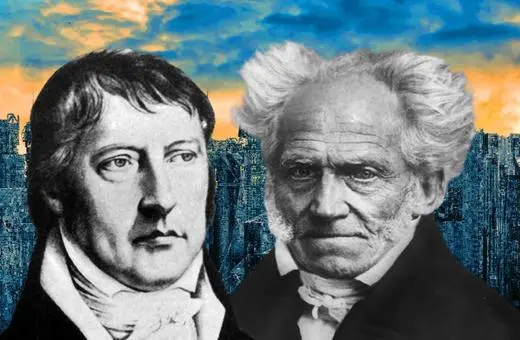

Without Ludwig Wittgenstein, Martin Heidegger and Adolf Hitler, all born within the same five months of the year 1889 and a radius of 380 miles, the face of academic philosophy would most likely look quite different.

___

Yet, the distinction between the two schools is everything but clear-cut, and many philosophers defy or try to overcome it altogether. Nonetheless, students who want to study the Anglo-American canon alongside authors from Europe, let alone non-Western traditions, will often find themselves sent away. Those interested in Nietzsche, Foucault, Merleau-Ponty, Deleuze, Derrida or even Hegel, Husserl, Heidegger, Sartre or de Beauvoir, will at most Universities switch to other departments: Religious Studies, French, English or German Studies, Gender Studies, Comparative Studies, history and more.

This remarkable status quo is the product of an extraordinary confluence of economic, world-political, socio-historical events on the one hand, and a small handful of wilful, determined, highly influential and idiosyncratic personalities on the other. Without Ludwig Wittgenstein, Martin Heidegger and Adolf Hitler, all born within the same five months of the year 1889 and a radius of 380 miles, the face of academic philosophy would most likely look quite different.

Philosophy as science or as pseudo-science? Nothingness meets Nonsense

Join the conversation