Laurie Penny is a columnist for New Statesman and the author of Meat Market: Female Flesh Under Capitalism. In 2010, her blog Penny Red was nominated for the Orwell Prize. Below, she discusses the differences between heresy and controversy and the importance, for democratic societies of people who challenge authority.

Should we celebrate heretics?

Well, I think that the British political culture (in particular) is very in love with the idea of controversy and very much likes the façade of high-profile disagreement, debate and iconoclasm for its own sake. The difference between everyday controversy and heresy, particularly useful heresy, is that heresy is the telling of particular truths that either expose authority and oligarchy or undermine its premise. This is why Galileo and Darwin were considered heretics, but Isaac Newton and Louis Pasteur were not.

Not all heretics set out to be iconoclastic and to challenge power. If you go down the centuries and look at people who have been considered heretical, a lot of what you see are people who, when confronted with truth and discoveries, felt that they had to make those known as a matter of principle. They were not prepared to keep quiet for the sake of maintaining the status quo. I think that kind of heresy is very different and far more powerful than challenging authority for its own sake.

Would you say that these powerful heresies are ones that people feel compelled to expose whether or not they're inconvenient, or are they more powerful specifically because they're inconvenient?

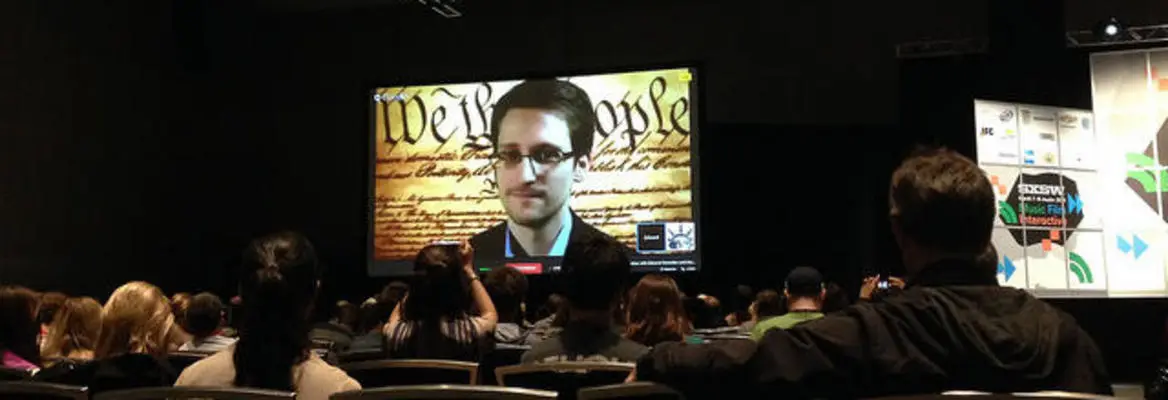

The more inconvenient they are, the more courage is involved in speaking about them. We speak about heresy and the persecution of heretics as something from the past, but in reality people are being pursued, imprisoned and threatened right now. In particular, those who expose state secrets that governments would rather keep private, for example, state surveillance: Edward Snowden is in exile, Chelsea Manning is in prison, probably for many decades; and when I raised this issue with [former high-ranking civil servant] David Omand, despite him talking a good game about Galileo and Darwin, he immediately said that, in his ideal world, he would still have had David Miranda, who was charged with offences under the Terrorism Act, in custody. I think that is chilling.

Is there a difference between those heretics who create an idea, come up with or discover something, and heretics who simply expose something that is already happening?

I don't think there is an important difference. Heresy is more about principle, commitment, pursuit of truth and justice at all costs. The (so-called) heretic who I think deserves more attention is William Tyndale, the first Bible martyr, who went to the stake for trying to publish the Bible in English.

Of course he was pioneering the use of a new technology – the Gutenberg press – but his heresy was to make available the machinations of the power of the church to ordinary people. While not a new discovery, it was a new way of looking at power – that was what was so threatening. Of course, 50 years later, everybody was reading the Bible in English.

So do you think heresy is purely positive? Can there be a negative or a false heresy, or one that's done just for the sake of heresy without having any useful content?

Join the conversation