When we snap a photograph, we think we’ve captured a moment in time, in reality. It is this experience that inspired Susan Sontag’s ‘ecology of images’, in her seminal essay ‘On Photography’. But philosopher Peter Szendy argues that to organise pictures, photographs and images into a system is impossible. Instead, we need to insist on the open-endedness of images. In doing so, we can better understand their relationship to reality.

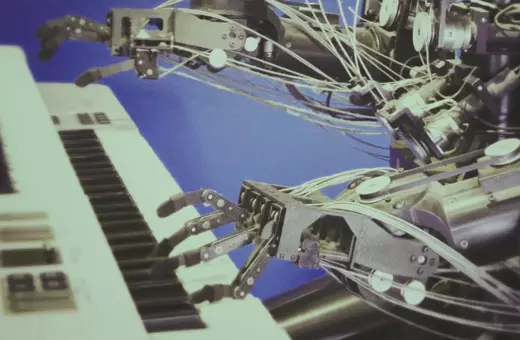

Statistics prior to Covid-19 indicated that there were more than three billion images circulating each day on social media. This is equal to hundreds of thousands of images during the time it took you to read this sentence. In 2019, YouTube boasted on its official blog that there were more than 500 hours of video uploaded every minute, equal to 720,000 hours a day, and the equivalent of more than 80 years worth of video. This is more than a lifetime of images every day. This overflow has probably increased exponentially, not only because the pandemic has drastically shifted our gazes towards screens but also because another iconological tsunami has hit our contemporary iconosphere: AI, which already has generated, according to recent figures, more images in a year and a half than photography has in 150 years. Not to mention other kinds of images made by machines for machines (from automatic licence plate readers, to facial recognition or imaging systems designed to oversee shipping and logistics). American artist Trevor Paglen, in a groundbreaking article, has suggested that these pictures constitute an “invisible visual culture,” with humans “rarely in the loop” of their circulation.

___

An ecological approach to pictures is meant here as an antidote to the consumerist logic of their infinite surplus.

___

Such is, briefly and bluntly stated, the context in which we can—and have to—think about Susan Sontag’s notion of an “ecology of images.” What did she mean by it? And how are we to appropriate it, build on it, and reformulate it for today or tomorrow?

___

Powerful and compelling as it is, Sontag’s idea of an ecology of images remains exclusively anthropocentric: her only question is what images do to us, human beings.

___

"An ecology not only of real things but of images as well:” these are the last words of her 1977 essay On Photography, and their meaning can only be inferred or guessed from the preceding paragraphs. An ecological approach to pictures is meant here as an antidote to the consumerist logic of their infinite surplus: even if images are not threatened by extinction or exhaustion, even if they are “an unlimited resource,” there is still, Sontag argues, “reason to apply the conservationist remedy.” And the reason becomes clear when she returns to the same idea one year before her death in Regarding the Pain of Others: we are “flooded” in images “that once used to shock and arouse indignation,” she writes, and as a consequence, “compassion, stretched to its limits, is going numb.” But her conclusion, in 2003, has a distinctly pessimistic tone: “There isn’t going to be an ecology of images,” she concludes abruptly, radically disbelieving the very possibility that one could “ration horror” and “keep fresh its ability to shock.”

Powerful and compelling as it is, Sontag’s idea of an ecology of images remains exclusively anthropocentric: her only question is what images do to us, human beings. Can’t we imagine, though, another way of looking at pictures and their plethoric numbers? Isn’t there a perspective that would match the iconological consequences of the Anthropocene, a concept that has emerged twenty-five years after Sontag’s On Photography?

Join the conversation