As Russia’s war against Ukraine continues, much of the focus has been on the apparent war crimes being committed. This line of thinking can be seen to suggest that the problem here is excessive violence, not the war itself. In his famous War and Peace, Leo Tolstoy put forward the argument that humane war is as absurd an idea as humane slavery, and that believing in it could distract us from what the real moral goals should be: the end of slavery and the end of war. But even if Tolstoy was wrong, we should also consider what the world would be like where the policing of war was a lot stricter. Who would be doing the policing, and could we be sure that the relationships of domination we find in local policing would not be replicated at the global scale, asks Samuel Moyn.

In my recent book Humane, I outline a modest and narrow argument that making objectionable practices less objectionable—especially in the name of reducing suffering—can possibly either legitimate or perpetuate the practices themselves (or do both). I hope the argument, framed for the sake of questioning activist and public priorities in America’s war on terror, is more broadly useful in an age debating the relationship of abolitionist politics to “harm reduction” across the political landscape.

___

___

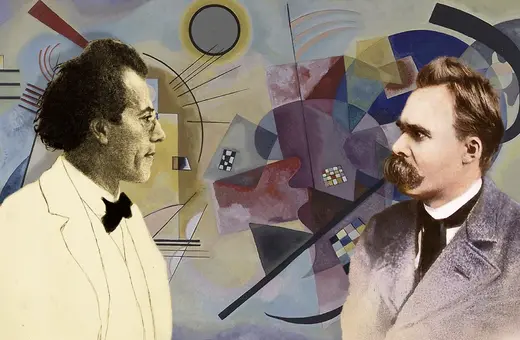

I begin Humane with a portrait of the moral reasoning of Russian aristocrat and novelist Leo Tolstoy, who was present at the creation of the first Geneva Convention of 1864 and sounded a warning from the start about the risk of the agenda of humanization. As I narrate, Tolstoy’s character in War and Peace, Prince Andrei, supposed that leaving war brutal would result in fewer cruel wars. His reasoning was that making war less cruel would increase overall cruelty in the world, because it would make war more regular and postpone peace. Others, like the Prussian theorist Carl von Clausewitz and the Prussian-American scribe of the rules for the U.S. Army in the Civil War and after, Francis Lieber, similarly believed cruelty would shorten wars.

To be clear, I don’t believe this is credible. More importantly, however, is that Tolstoy’s character adopted the same ethical standard—reducing cruelty—as the humanitarian-minded thinkers he opposed. Equally important is that he offered an empirical conjecture. Even if it is generally credible, an empirical conjecture will almost certainly admit of exceptions. In light of this possibility, Andrei should have stressed not the intensification of wartime atrocities, but the contingent risk of humanizing violent corporal practices like war.

___

___

This is a view Tolstoy would consider later in his career, after a conversion experience inspired him to give up Andrei’s shortsighted, consequentialist outlook. (For anyone hewing to Jesus’s demand in the Sermon of the Mount to “resist not evil,” it is not just because it might make the world a better place.) However, Tolstoy still considered contingent risk through empirical conjectures. Now writing as a pacifist, Tolstoy thought the contingent risk was not that wartime brutality would lessen cruelty, but that humanizing war might legitimate or perpetuate war itself. By developing two fundamental comparisons between corporal practices, Tolstoy explored two causal pathways through which that contingent risk could be incurred in fact—pathways that in Humane I go on to argue have been followed in our time, as America’s “endless war” has ground on and on.

Join the conversation