Western commentators tend to think of Islamic jihadists as enemies of our civilization. But what animates the cause of Radical Islamists are ideas borrowed from Marxist and post-colonial Western thought. Jaan Islam argues that until we recognise the familiarity of the jihadist worldview, we will fail to reach our political aims, including peace.

When people talk about ‘jihadis’ or Muslims more generally, the desire to classify people as ‘the other’ makes us frame them in neatly-packaged stereotypes that tell us more about the observer than the subject of observation. The ‘jihadi’ in the mind of the western observer is ruthless, barbaric and lives on the fringes of civilization. Such categorizations make it very difficult to understand how they actually understand the world, and more importantly, how they understand their goals in relation to the rest of us.

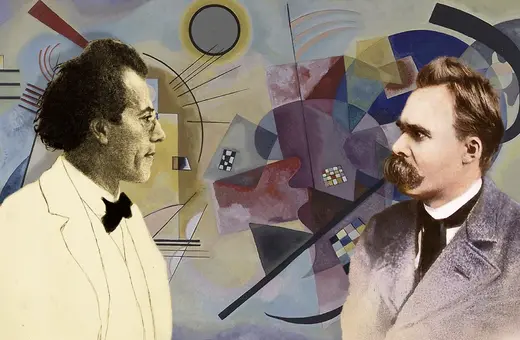

To begin to understand the jihadis’ world view we need to trace how the Mujahideen intelligentsia forged, sometimes surprising, ideological connections with western political theory. The vast literature these scholars draw upon include Neo-Marxism and postcolonialism. Scholars who serve as front-line clerics for Islamic struggles today not only read figures like Karl Marx, Friedrich Nietzsche, Edward Said and Wael Hallaq, but incorporate these ideas into a global solution to the world’s problems. These include wealth inequality, neocolonial exploitation, and authoritarianism in former colonial states. While the academy likes to study stereotypical jihadists by presupposing their ideological separation from the so-called “West”, these intellectual connections with Western intellectuals force political theorists to rethink “the other” as closer to them.

The Decolonial Vision for an Islamic State

One of the most “delectable” accounts of serious intellectual exchange between Islamic revolutionary thought and decolonial theory is the interaction between Wael Hallaq—a humanities professor at Columbia University—and the famous Mujahid ideologue, Abu Qatada al-Filistini. For those who don’t know him, Abu Qatada is a famous Palestinian jurist, theorist of jihad, and former London resident for nearly 20 years.

In 2012, Hallaq published a book called The Impossible State, which argued that the concept of an ‘Islamic state’ was an oxymoron. Hallaq was not claiming that the classical Islamic tradition was apolitical, or that there did not exist Islamic conceptions of government in its 1400-year history. The argument was far more nuanced: Hallaq believes that modern concepts of the state within a postcolonial context have no basis in the premodern Islamic tradition.

___

The state is not a neutral institution, compatible with any values-system, including that of Islam.

___

Consider what differentiates, say, a medieval Empire to the modern state: mass-surveillance, bloated bureaucracies, government regulations covering all aspects of human life, prison systems, national education, the list goes on. Hallaq posits that any Islamic government would end up adopting the same colonial institutions that were responsible for the subjugation of Muslim countries for decades, participating in the same neo-colonial system of capitalist exploitation. The state is not a neutral institution, compatible with any values-system, including that of Islam. The modern state already instantiates its own values and world view, so any attempt by self-identified Islamic reformists, such as the Muslim Brotherhood, to use the state in order to bring about a world of Islamic Values is a non-starter.

Here’s where Abu Qatada comes in. An avid reader, Abu Qatada runs a book review series entitled “A Thousand Books before Death”, that includes reviews of texts by Karl Marx, Friedrich Nietzsche, Karl Popper, and of course, Hallaq’s The Impossible State. In his hour-and-a-half review, Abu Qatada surprisingly agrees with Hallaq’s argument:

Join the conversation