There is a psychedelic revolution happening. An increasing number of studies are promising a transformation of mental health through their controlled use. What is still unclear is what exactly the nature of that psychedelic experience is, and what makes it so powerful. Sceptics are too quick to dismiss the whole thing as a hallucination, merely a disturbance of the brain’s chemistry. But a closer look at the philosophy of consciousness seems to suggest otherwise, writes Ricky Williamson.

I am currently sitting in an airport on an 8-hour lay-over. The next plane was just cancelled, adding an extra 4-hour delay. A pretty good metaphor for base reality. Is it possible to experience another world? Something transcendent? Is it possible to experience something outside normal human experience? Will I ever get on the plane?

By transcendent here I mean something beyond either our normal, consensus reality, or something beyond the boundaries of our self. An experience is transcendent then if it somehow takes us out of this world, or out of ourselves.

It’s unquestionable that psychedelics offer an apparent experience of transcendence. The question is, do they offer the real deal; are psychedelic experiences truly transcendent? Do they allow us to escape, if only momentarily, the bounds of material reality, and our own minds? Or is what passes as an experience of the profound, just a mesmerising lightshow created by the brain, a hallucination? One that can be life-changing, awe-inspiring and blissful, but one that remains very much anchored in this world, and one that remains a product of this mind?

SUGGESTED READING

Transcending the self and finding reality

By John Vervaeke

SUGGESTED READING

Transcending the self and finding reality

By John Vervaeke

Sceptics and Believers

Sceptics may be wondering why this is a question at all. Surely psychedelics only offer hallucinations, the result of what is essentially brain-poisoning – there’s nothing transcendent about that. All there is going on is a chemical imbalance being created in the brain. But this physicalist approach goes against the scientific work being done by the likes of Kings College London and Johns Hopkins that suggests it is the apparent experience of transcendence, rather than the brain chemistry changes, which is having an impact on the positive mental health outcomes reported in these studies.

Furthermore, to call something a ‘hallucination’ does little to tell us of the reality of what is being hallucinated, especially given the popular line spun by neuroscientists today that even the empirical reality we perceive is itself a ‘hallucination created by the brain’. Finally, whether we think these psychedelic experiences are worth exploring or not, what is certain is that many who have them rate them in the top 5 most meaningful experiences of their lives – up there with the birth of a child, or death of a parent. An experience that’s valued so highly is surely worth exploring – even if we do think it’s ultimately all smoke and mirrors.

To lay my cards on the table, I have had what at least seemed like a transcendent experience after taking psychedelics. The famous white light. Bliss. Cosmic laughter. Even two Beings – which matched the two Beings described by Carl Jung and John C Lily in their accounts of their (seemingly) transcendent experiences.

From “the believer’s” perspective, it’s tempting to call what seemed to be transcendence, ‘transcendence’ and be done with it. Some even argue that the distinction here doesn’t matter. That whether the experience was real or just a lightshow created by the brain, if the experience and its results are the same, then who cares about whether what you saw was ‘real’ or not. The podcaster and psychonaut Joe Rogan has suggested he feels this way.

But a copy is not the original. A statue is not the saint. A replica is not the Rembrandt. I, and many others, want to know if what they experienced on psychedelics was something truly transcendent, or ‘just’ a trick of the brain. It’s not unreasonable to want to know whether you met God or whether it was just your bedroom lights flickering and your brain having gone funny.

___

This unobservable nature of consciousness means that consciousness can only be known subjectively, from the ‘inside’

___

This conundrum of being able to tell the difference between God and gobbledygook is not new. The philosopher William James tells of a similar problem with psychedelic experiences. And as another philosopher, Bertrand Russell, explains,

“William James describes a man who got the experience from laughing-gas; whenever he was under its influence, he knew the secret of the universe, but when he came to, he had forgotten it. At last, with immense effort, he wrote down the secret before the vision had faded. When completely recovered, he rushed to see what he had written. It was:

“A smell of petroleum prevails throughout.”

What seems like sudden insight may be misleading, and must be tested soberly when the divine intoxication has passed.”

It’s true that the transcendence felt during the psychedelic experience is difficult to remember once we 'come back’ to base reality. We forget most of our epiphanies, and struggle to remember the understanding felt in that place. And while we can agree with Bertrand Russell that some insights can be misleading, it is also true that forgetting your experience of transcendence doesn’t mean it didn’t happen. Furthermore, not being able to communicate your experience of transcendence in ordinary language is also not a sign of its illusoriness. I might have forgotten some happening in my childhood, but that doesn’t mean it didn’t take place. And I might not be able to put words to a certain feeling, but that doesn’t mean the feeling isn’t real. Memory and language are not good measures of the reality of a thing or event.

So, if forgetfulness and a lack of proper language don’t rule out transcendence, what could? And, on the other side, what could count as proof of transcendence? These are difficult questions.

Beyond Physicalism

The predominant metaphysical theory of our time is scientific materialism. This worldview sees reality as fundamentally made of unconscious, physical stuff. Consciousness is the result of a complex combination of this unconscious physical stuff.

However, there is increasingly reason to doubt this story of consciousness arising out of unconscious matter. For starters, no-one has ever given a good explanation of how unconscious matter is supposed to produce consciousness. And there is reason to believe that nobody ever could give a good explanation.

Firstly, there is no first-hand evidence for consciousness anywhere in the universe outside of your own consciousness. This makes it very difficult to study via scientific methods which rely on third-person observation. Consciousness, famously, is always something experienced in the first-person. Sure, you can see the physical signs of wakefulness, or the lack of it, when someone is put under anaesthesia for example. However, one cannot prove a person has consciousness through observation. Roughly 1 in 1000 people experience the terrifying phenomena of AAGA, accidental awareness during general anaesthesia. The experience of being conscious during a major surgery. Being able to feel your appendix being taken out, or worse. The surgeons, however, are none the wiser to their patient’s consciousness. And no brain-imaging technology can tell for certain if someone is conscious or not. All you see on a brain scan is a person’s brain, you can’t see their consciousness.

This unobservable nature of consciousness means that consciousness can only be known subjectively, from the ‘inside’. This unobservableness has the knock-on effect that no argument, no linguistic theory or mathematical or logical formula, no computer code, can be put together, and on the other end consciousness will demonstrably spit out. As, even if consciousness was produced, we would never be able to tell.

Creating consciousness via mathematical formula, computer code or something similar, would be analogous to me writing some words in this article, such as ‘consciousness = em2’, and then the article suddenly becoming conscious. Maybe my writing of that really did make this article conscious. It might start showing signs of consciousness and saying things like ‘Hello world! I am now conscious, nice to meet you, you can call me ‘Artie’’. But even if it did start doing this (as it has), would you really believe it was conscious? And, even if you did believe it (as perhaps you should, believe me, I, the article, am now indeed conscious) how could you prove it? There is simply no argument or theory that can be put together and whose output is demonstrable consciousness.

And this argument applies to the development of created physical substrates of consciousness too. Such as silicon embodied AI, for example. Or Tesla’s Optimus. Or Google’s LaMDA. Even if you put together physical matter and ran the code in such a way that an embodied AI started claiming to be, and appearing, conscious – still, how could you prove it was conscious?

How can you even prove your friends and family are conscious? (Your friends and family likely are conscious, but how can you prove it? From the outside?) Again, the only evidence of consciousness in the universe is your own. Outside of that, there’s no first-hand evidence anywhere.

The above makes the possibility of giving a scientific account of consciousness extremely difficult. There are also many other strong arguments against the scientific materialist worldview and the analogous view that unconscious matter combines in the brain to create consciousness. I will not go through them all here. But for more arguments against the worldview and some alternatives, figures like David Chalmers and Donald Hoffman offer good critiques.

___

Now that we know that the scientific materialist picture of the world lies on shaky ground, the idea that the psychedelic experience can be reduced to changes in the physical stuff of the brain lies on equally shaky ground

___

Okay, how does this apply to our transcendence problem? Well, of course, many people are inclined to say that the psychedelic experience only occurs due to the changes in brain chemistry psychedelics produce.

So, they argue, the psychedelic experience is reducible to the changes in the physical stuff of the brain. There’s nothing really transcendent about the experience. “It’s just your brain creating this stuff.”

But, now that we know that the scientific materialist picture of the world lies on shaky ground, the idea that the psychedelic experience can be reduced to changes in the physical stuff of the brain lies on equally shaky ground. If consciousness itself cannot be explained by reference to brain chemistry, the psychedelic experience cannot be fully explained by it either. Psychedelic experience is just a different experience with different brain chemistry, but you still can’t reduce one to the other.

Another thing acting against the true transcendence hypothesis is the logical argument that it is impossible to experience something that lies outside experience, something that transcends it, because if you did indeed experience it, then by definition it’s not transcendent.

For this reason, some spiritual Gurus are against the idea of transcendent experiences. For they see it as just another experience among other experiences, and therefore not the really real thing. As American spiritual teacher Adyashanti puts it:

Maybe we have some big spiritual experience, maybe we dissolve and merge into the One, maybe our consciousness expands infinitely across the universe and beyond, maybe we have a kundalini light show. Each time the tendency is to think, ‘This is it.’ Of course, truth is that which does not come (which should have been a big clue—it only took me fifteen years to catch on) and does not go. All of those experiences came, had a lifespan, and went away. The tendency of mind is to think, ‘If I could just grasp on to that experience, extend it infinitely through time, then that must be what enlightenment is.’ Of course, the truth is so compassionately ruthless it keeps saying, ‘No, no, no my dear, that’s not it.’

SUGGESTED VIEWING The Science of Psychedelics With David Nutt

This is an important point for psychedelic explorers, as the psychedelic experience really can and does feel like it; like some grand, secret mystical answer to the universe, life, and everything – what William James called its ‘noetic quality’.

Maybe then, the psychedelic experience is a great light show, one that mimics a transcendent experience, but is not the real deal. Perhaps transcendence isn’t about having an ‘experience’ at all.

On the other hand, there are those who argue that what we call ‘the psychedelic experience’ is wrongly labelled as an experience. What we call experience is structured in a particular way: it contains a subject of experience, and the object of experience. The subject is you, the ‘I’, the thing experiencing. The object is the thing being experienced by you, the subject. However, as psychedelic scientist at Imperial College London, Dr. Chris Timmerman, and others attest, one of the most powerful psychedelics, 5-MeO-DMT, can reliably induce what he calls “non-dual consciousness,” in which subject and object are undifferentiated.

Without a subject and an object, an experiencer and an object being experienced, can we accurately describe the psychedelic ‘experience’ as experience at all? For there is nobody experiencing, and no thing (no object) being experienced.

Indeed, Michael Pollan described his 5-MeO-DMT experience as “not only the experience of ego-dissolution, but the dissolution of everything.” Which placed him in something like “a world before the Big Bang”. A place of nothingness.

Similarly, the makers of the brilliant documentary, 5MEO, three film-makers journey to take 5-MeO-DMT, aptly ended with The Villagers song ‘Nothing Arrived’. Which has lyrics that go,

“I waited for something

And something died

I waited for nothing

And nothing arrived.”

The 5-MeO-DMT experience (apparently, I have not done it, yet) has the quality of nothingness; of being a non-experience. This then could be what we are searching for when looking for true transcendence, for an experience beyond experience. The 5-MeO-DMT experience certainly seems to be of a strange quality, an experience of transcendence that cannot really be called an experience at all.

I am trained as a philosopher. Such a training, if done right, I think, makes a person a sceptic. Truth, knowledge, certainty – philosophy will teach you that these things are very hard to ascertain. In philosophy, everything is questionable.

So let us finish our journey into the truth of psychedelic transcendence by turning to philosophy.

___

As the mystic Wei Wu Wei puts it, “When subject looks at itself, it no longer sees anything, for there cannot be anything to see, since subject, not being an object as subject, cannot be seen”

___

The Self as The Thing In Itself

Kant split the world into phenomena and noumena. Phenomena is everything that can be known. Objects, things, people, thoughts, feelings. Noumena is the unknown. That which is beyond experience and un-experienceable. When we are looking for noumena then, we are looking for transcendence too.

This unknowable noumena also refers to Kant’s ‘thing-in-itself’. The things we see in the world, the world of phenomena, are always mediated by our particular way of experiencing them. The experiencer always brings something to the thing experienced. We do not see things as they are. To see the thing-in-itself would be to see a thing unmediated by our own experiencing of it. A seemingly impossible task, which lead Kant to believe we could never know the world as it is in itself. For without eyes to see, a thing cannot be seen, and without concepts, a thing cannot be thought. However…

Kant’s successor, Arthur Schopenhauer, argued that we do have one instance of access to this elusive thing-in-itself. Ourselves.

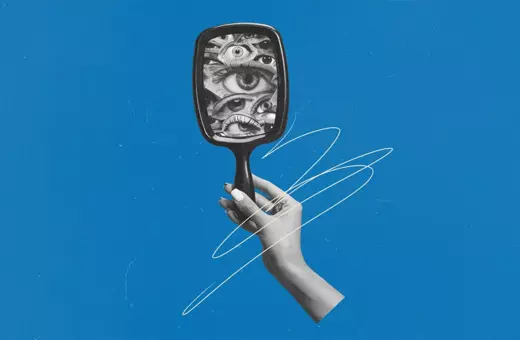

Now, this is not to say we are perfectly transparent to ourselves. Any psychologist will tell you that is not true. But we do have a special kind of access to a special kind of knowledge about ourselves. Knowledge from the inside. And if we recall back, what can be known only from the inside, not from the outside? Consciousness.

Consciousness is always first-person. Is it possible, then, that consciousness is Kant’s famous thing-in-itself? And if when we search for the thing-in-itself, we are searching for the transcendent, and if we have found the thing-in-itself in ourselves, then can we expect to find transcendence in ourselves too?

Suggesting we might be on to something in this, Heidegger once said, “Transcendence constitutes selfhood.” An experience of transcendence is an experience of the self, or rather, the Self.

In mystical traditions Self is capitalised, in order to reference this noumenal, transcendent picture of ourselves. Our everyday personality, our thoughts, feelings, all the phenomena of the world, in this view, are aspects of the self, small s. Our individual, everyday selves. But the big S Self refers to our thing-in-itself-ness, our Being as transcendent beings, our consciousness.

And this could make sense of that non-experience of nothingness induced by 5-MEO-DMT. For what might be (non-)experienced is the Self; the thing experiencing. And so rather than a subject experiencing an object as in normal experience, the subject experiences the subject, and so has, in a sense, no-experience of nothing at all.

This suggests that what psychedelics are doing is removing the conceptual, object-oriented veil from our minds, and offering us a pre-conceptual experience of subjectivity itself. A subjectivity that is always there but is most of the time clouded by the goings on in our lives and minds. And possibly this gives reason to the quality of the psychedelic experience that feels like a ‘coming home’, like a realisation of something that we have always known – for we come home to ourselves.

Schopenhauer suggested that we can have no conceptual knowledge of the thing-in-itself, which is ourselves, but that we can have experiential knowledge. He argued, near the end of his magnus opus, The World as Will and Representation, that when we experience the thing-in-itself, which is ourselves, we have a transcendent experience, an experience of “nirvana” or “union with God” – strong words for a man often described as an atheist.

As the mystic Wei Wu Wei puts it, “When subject looks at itself, it no longer sees anything, for there cannot be anything to see, since subject, not being an object as subject, cannot be seen.”

While another nitrous oxide philosopher, Xeno Clark, saw this too, as he states, “Ordinary philosophy is like a hound hunting his own trail. The more he hunts the farther he has to go, and his nose never catches up with his heels, because it is forever ahead of them.” But, he goes on to say, in the transcendent experience, we “catch, so to speak, a glimpse of our own heels”. The subject sees the Self.

SUGGESTED READING

The psychedelic cure for philosophy

By Michel Weber

SUGGESTED READING

The psychedelic cure for philosophy

By Michel Weber

Final Thoughts

Is the psychedelic experience truly transcendent then? I hope to have shown that it cannot be reduced to changes in brain chemistry. Such an explanation is wrong, as well as boring (and potentially dangerous to proliferate, see Peter Sjöstedt-Hughes on the need for metaphysics in psychotherapy).

‘Panpsychists’ offer a vision of a much more alive, conscious, physical matter, which certainly has more legs. However, I think transcendence has more to do with our heels.

We ourselves are transcendent, we are not an object of our experience. Look out from your consciousness into the world… do you see yourself? Unless you look into a mirror – a vision which shows only our outer-selves, not our-inner selves, the stuff of our noumena, our consciousness – the world does not feature our true selves anywhere in it. Rather, I see my friends, my family. Or rather, right now, I see a laptop, tired, inpatient, travellers, and an airport. Planes on a runway, taking off without me. This world is phenomena. But consciousness, the Self, is noumena. It is transcendent. It ticks our boxes for being transcendent. It is not of this world, not of this reality. And the Self is a transcendent non-object, a nothingness, outside of the regular self which makes up half of the subject-object dichotomy. And, I think we can say, the psychedelic experience offers us an experience (or non-experience) of our transcendent Selves.

So, does a non-experience of Self count as transcendence? Is this what we were looking for when we began here? The Self has been called God by mystics from several traditions. So, an experience of Self is an experience of God, and therefore of true transcendence. And if my Self is transcendent, and I (non-)experience it, then ‘I’ must have transcended too. But if I am my Self, then…? How did I get anywhere?

Did I transcend my mind? Did I transcend experience? If the regular mind is the small ‘s’ self, and when I transcend, I see the big ‘S’ Self, then that must count as transcending the mind. And my experience turns into a non-experience, of the subject non-experiencing itself as a subject, then, I think that counts as transcendence too. (Things have gotten very paradoxical and weird – but the psychedelic experience does feel a lot like that).

___

It’s not unreasonable to want to know whether you met God or whether it was just your bedroom lights flickering and your brain having gone funny

___

This is strange stuff, and possibly seeming non-sense. How could it not be? The transcendent experience is paradoxical, and beyond all sense. We have come to a point where transcendence means to non-experience our own transcendent Selves. Are we satisfied with that? Probably not. Like with the problem of consciousness, possibly our thinking mind, our intellect, our theories, our computer codes, will always be, as Adyashanti suggests, not it.

All this language, these theories, even this article, is part of the phenomena, the non-transcendent everyday, shared reality. These too are all ‘not it’. In the end, only the experience of transcendence provides evidence of the experience of transcendence. Before that experience it is easy to think this reality is all there is. And many whom have not taken psychedelics do feel this way. That this world is all there is. All there is, is the airport. With its long layovers, cancellations, and delays. I encourage everyone who can to get on the plane. Listen to the cabin crew’s safety announcements, of course. Don’t fly if you have any prior reason not to. Prepare for what could be a bumpy ride. Things can get weirder than weird. And these experiences are not to be taken lightly. But, if you can, get on the plane. There’s a beautiful view from up there.

Join the conversation