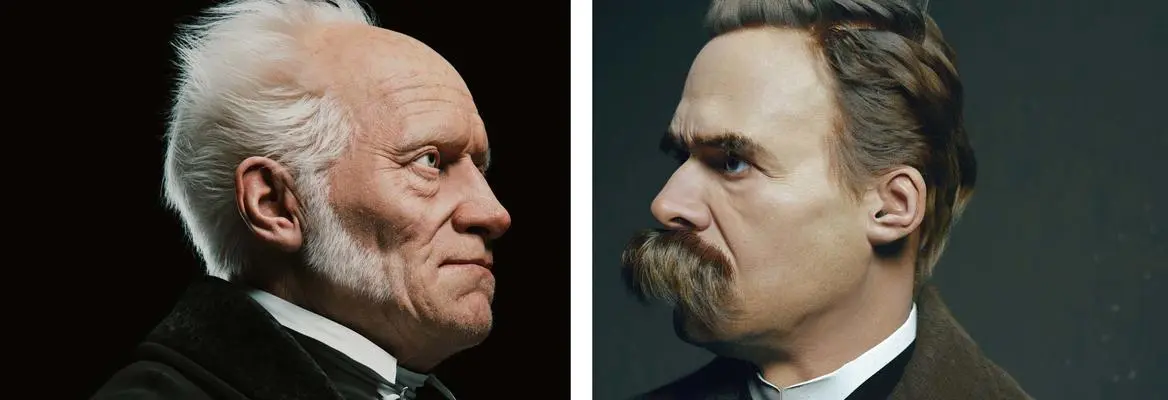

We know that every life contains a good deal of suffering. However, what counts is how we respond to it. Schopenhauer recommends a limiting of desire and resignation from life. While Nietzsche recommends an artistic response to the tragedy of life and an embracing of the suffering it entails. The best response, really, might be to laugh, writes Joshua Foa Dienstag.

“If there are happy people on this earth,” wrote E.M. Cioran, “why don’t they come out and shout with joy, proclaim their happiness in the streets? Why so much discretion and restraint?”

Some people have easier, more privileged lives than others, but all human lives contain suffering and some contain a great deal of it. Centuries of technological progress, although relieving some sources of extreme distress, have on the whole not made humans much happier, as numerous studies confirm. What explains the persistence of suffering and what attitude should we take toward it?

SUGGESTED READING

Hobbes vs Rousseau: are we inherently evil?

By Robin Douglass

One powerful answer to this question was offered by Arthur Schopenhauer, the German philosopher born in 1788 whose book of pessimistic essays Parerga and Paralipomena (“Appendices and Omissions”) became wildly popular after its publication in 1851. “Life,” he famously wrote, “is a business that does not cover the costs.” Human desires, he thought, would always outstrip the world’s potential to satisfy them, leaving each individual in a kind of permanent deficit.

SUGGESTED READING

Hobbes vs Rousseau: are we inherently evil?

By Robin Douglass

One powerful answer to this question was offered by Arthur Schopenhauer, the German philosopher born in 1788 whose book of pessimistic essays Parerga and Paralipomena (“Appendices and Omissions”) became wildly popular after its publication in 1851. “Life,” he famously wrote, “is a business that does not cover the costs.” Human desires, he thought, would always outstrip the world’s potential to satisfy them, leaving each individual in a kind of permanent deficit.

Writing a generation later, Friedrich Nietzsche, who had once considered himself Schopenhauer’s disciple, offered a pointed rebuttal. Acknowledging the ubiquity of suffering, Nietzsche nonetheless believed that Schopenhauer had failed to respond adequately to the challenge it posed.

In fact, he thought, the older philosopher had suffered a failure of nerve. Rather than toting up pleasures and pains like an accountant, Nietzsche thought that our confrontation with suffering could be the key to a different kind of attitude toward life; “a hammer and instrument with which one can make oneself a new pair of wings”.

The confrontation between these two perspectives has much to teach us about how to think of suffering and life in general. Is the goal of life to achieve a surplus of pleasure over pain? Or is there another way to measure our experiences that is less mechanistic?

Is the goal of life to achieve a surplus of pleasure over pain? Or is there another way to measure our experiences that is less mechanistic?

Schopenhauer was writing just as the first translations of Buddhist texts into Western languages were being made and he does endorse, in a sense, the Buddhist idea that “life is suffering,” that is, that suffering is the substance of life. Humans are largely motivated by pain – by thirst and hunger for example – and what we call pleasure is largely just the relief of those conditions, a relief that was always fleeting in comparison to the pain that preceded it. “All enjoyment,” he wrote, “is really only negative, only has the effect of removing a pain, while pain or evil … is the actual positive element”.

This explains why we might feel perpetually in deficit. We respond to some source of pain, only to have others spring forward to take its place. And the relief we win is always temporary with the return of suffering always on the horizon. What’s more, we constantly experience the ‘leveling-up’ phenomenon where things that once brought us pleasure become just part of the scenery.

Join the conversation