A few weeks ago saw the sequin-sprinkled finale of the second series of BBC2’s Great British Sewing Bee, an eight-part stitch-off of amateur home-sewers from the makers of The Great British Bake Off. If this newer show hasn’t amassed quite the same devoted following as Bake Off, its dress-patterns-at-dawn format has nevertheless been cheerful watching.

Each week, ten hopefuls earnestly examined eyelets and finished French seams as they competed for the crown of “Britain’s best amateur sewer”. One of the miracles of the show was how perma-tanned presenter Claudia Winkleman’s infuriating fringe managed to escape an expedient snip, especially given the number of sharpened scissors lying about. Aside from the banalities, what really makes the programme such a quiet and gentle triumph is its graceful acknowledgement of the craft of making clothes; its recognition of the exquisite artisanship of even the most basic dressmaking, and its sense of the extent to which we have forgotten how important these skills are to our daily lives.

Throughout the show, contestants have had to demonstrate a range of skills: adhering to simple patterns, managing alterations and meticulously fitting bespoke garments. In many ways, this is a homely and sensible sort of programme. With neither couture airs nor voguish graces, it taps in, perhaps, to our contemporary guilt about waste and celebrates scrupulousness in straitened times.

But it is also clearly part of the oddly pervasive “make do and mend” ‘50s nostalgia, so visible in our fetishism of vintage and retro stylings, that one might worry about its implicit re-instatement of traditional gender roles. Is this TV that is too domesticated? Perhaps. Yet what’s winsome about such domesticity is that it rescues clothes design from the inherent sexism of haute couture and the fashion industries to reclaim the design and fabrication of textiles as deeply skilled and powerfully artisanal work.

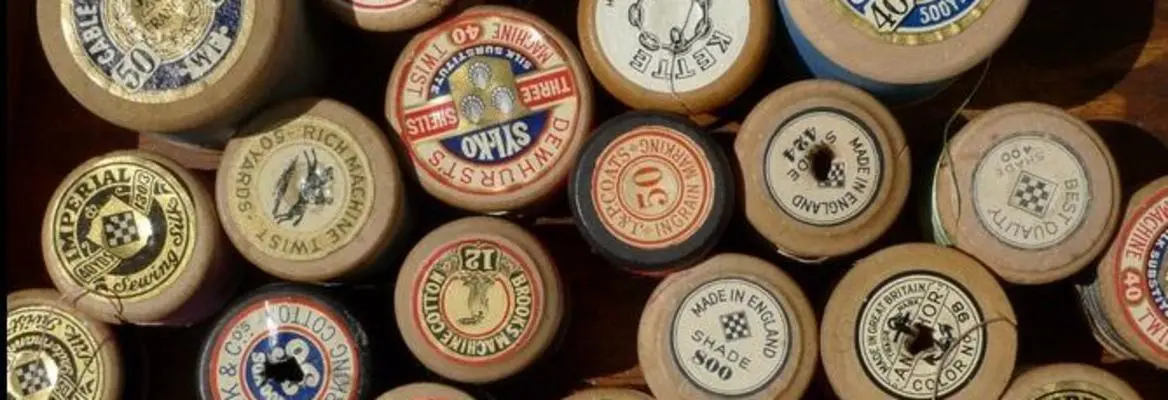

There is finesse and flair, intelligence and accomplishment in the mastering of material. There is divinity in the deftness of darting, sensitive top stitching and immaculate sheering; there is craft in bias binding and fly fastening, pressed patch pockets and spider-web thin rouleau straps. There is some small sort of quiet perfection in an unpuckered understitch.

The thoughtfulness that sewing demands is something you might know if you’ve ever taken up a complex hem or cross-stitched as a child. It calls upon a peculiar kind of attention: a sequential, temporary focus on a series of finite details, the triumphant mastering of which is necessarily forgotten in the whole. The final finish of a garment, after all, is in being able to wear it without concern for its workmanship.

But the remembering of the craft of clothes seems somehow more poignant and powerful in an increasingly artless internet age. If we worry about the decreasing dexterities of our ever-online culture, then perhaps the clothes we wear could serve to remind us, not only of the skill required in their making, but also in the clever calculations of pattern cutting and piece fitting. This is not to say one could ever overlook the unjust conditions of mass production so readily outsourced to third world countries – the materialist critique of material most certainly warrants our consumer action. But it is to say that the question of how clothes are made might say something about who we are.

Join the conversation