Many in the west believe that spending will save the economy in the wake of Covid-19. Arvind Panagariya argues debt must be kept under control if economies are to survive the crisis, and that India is showing early signs of getting it right.

A strict lockdown, beginning on March 24, initially kept Covid-19 cases in India at low levels. But amid a phased lifting of lockdown measures, the cases have surged. As of July 11, 2020, the total number of cases at 850,000 is the third largest in the world, behind only Brazil (1.8 million cases) and the United States (3.2 million cases). Taking recovery and deaths into account, the number of active cases is far smaller at 292,000.

SUGGESTED READING

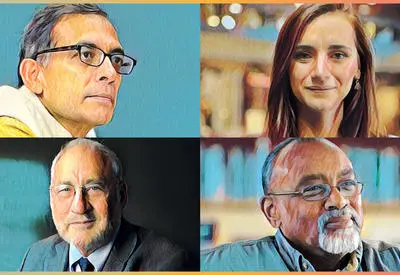

Groundbreaking economics at HowTheLightGetsIn

By

When seen against India’s vast population of 1.35 billion - compared with 210 million in Brazil and 328 million in the United States - so far, India has done well in managing the crisis. Indeed, India’s management looks particularly impressive when measured by the number of deaths despite its large size and low level of per-capita income. As of July 11, 2020, the total number of Covid-19 deaths stands at 22,674 in India, 71,469 in Brazil and 134,817 in the United States. Indeed, several countries with fewer cases of infection than India, such as the United Kingdom, Mexico, Spain and Italy, have seen significantly larger number of deaths.

SUGGESTED READING

Groundbreaking economics at HowTheLightGetsIn

By

When seen against India’s vast population of 1.35 billion - compared with 210 million in Brazil and 328 million in the United States - so far, India has done well in managing the crisis. Indeed, India’s management looks particularly impressive when measured by the number of deaths despite its large size and low level of per-capita income. As of July 11, 2020, the total number of Covid-19 deaths stands at 22,674 in India, 71,469 in Brazil and 134,817 in the United States. Indeed, several countries with fewer cases of infection than India, such as the United Kingdom, Mexico, Spain and Italy, have seen significantly larger number of deaths.

India’s management looks particularly impressive when measured by the number of deaths despite its large size and low level of per-capita income.

Like most countries around the globe, but unlike the handful of the countries in East Asia, India was initially slow to respond to the impending crisis. Whereas countries such as South Korea, Taiwan and Vietnam learned from their previous experiences with epidemics and put response mechanisms in place, India did not.

During 2009-10, the H1N1 virus hit the country hard, with resulting deaths running to several thousand. But the lessons from that experience did not get translated into preparedness against future epidemics. India began the Covid-19 crisis grossly short of supplies of masks, personal protective equipment (PPE) and ventilators. It also lost the crucial months of February and March when supplies of masks, PPE, ventilators and test kits could have been beefed up and dedicated Covid-19 testing facilities and hospitals created.

But once Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced the lockdown on March 24, governments at all levels— central, state and local — moved swiftly. Testing capability was quickly built up, patients were identified and quarantined, and contact tracing was done. In many jurisdictions, local officials exhibited remarkable capacity to trace contacts and quarantine individuals and localities.

India has also quickly ramped up testing facilities and hospitals dedicated to treating Covid-19 patients. From near nil, per-day production of PPE had risen to 600,000 and ventilators to 1,000 by the end of June. By the end of May, annual production capacity for N95 masks had reached 31.2 million and for 3-layer surgical masks to 1.5 billion. India is now in a position to export these items, except perhaps N95 masks.

Join the conversation