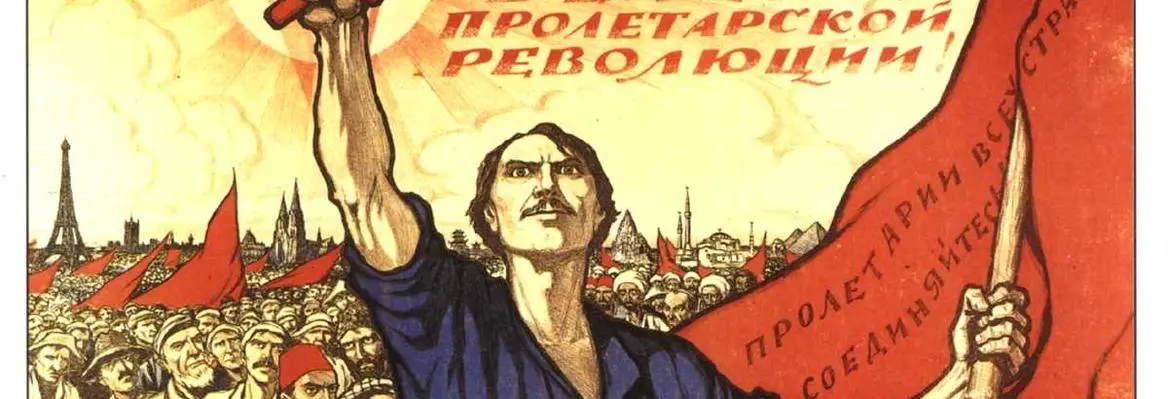

Given the radical ideological change that the November 1917 Russian Revolution brought, it's peculiar how little we speak about Soviet philosophers. One obvious explanation is that the government used philosophy to reinforce its ideology rather than allowing it to be a space for critical thinking and open debate. Fearful of giving philosophers too much autonomy, Soviet institutions not only exiled rebels but eventually marginalized even its main ideologues. Despite all these challenges, at least ten thinkers are worth our attention. There is one thing they all share - an interdisciplinary approach to their subjects. None of the thinkers below solely pursued philosophy – perhaps a happy by-product of the Soviet interference in academia.

___

“We have been nodding for so long that today we should learn anew how to distinguish life from death, reality from dream […] Diminished, in the Soviet way and without any energy, we lost the ability to understand politics […] The unreality of things and the zombie-like nature of humans has become the rule of life.”” — Merab Mamardashvili

___

The most known Soviet thinker, Mikhail Bakhtin (1895 -1975) has been dubbed as ‘a star of postmodern West’ and ‘a precocious post-structuralist’. A literary theoretician and philosopher of language, Bakhtin was interested in most of what, a few decades later, became the hot topics of postmodernism – discourse, the multiplicity of the self, hybridity, otherness, sexuality and subversion. In the Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics, published in 1928, Bakhtin puts forward the idea of ‘dialogism’, or ‘polyphony’, arguing that the reader, the writer, the work and the social context continuously influence each other; and that language is not static but constantly evolves. Immediately after publishing this book, Bakhtin got arrested and exiled to Kutanai, Kazakhstan, in 1929, where he worked as a book-keeper for six years. He returned to Moscow in 1940 to write his doctoral thesis on Rabelais and then became the chair of the Russian and World Literature Faculty at the University of Mordovia.

Much less known than Bakhtin, Merab Mamardashvili (1930-1990) has been called a 'Georgian Socrates' due to his preference for live dialogue over writing, as well as his lecturing talent as a professor at the Institute of Philosophy of the USSR in Moscow and the University of Tbilisi. His interests ranged wildly from the methodology of science to the role of consciousness in social beings, aesthetics and politics. He strongly opposed a ‘national philosophy’, saying that ‘I am fighting not for the Georgian language but for whatever can be said in Georgian. I do not need faith, I need freedom of conscience!’

___

“Phenomenology is the accompanying feature of all philosophy” — Merab Mamardashvili

___

Mamardashvili was interested in German and French philosophy – particularly Descartes, Kant, and Proust and phenomenology – and criticized his co-nationals for replacing the Enlightenment with patriotism. He saw nation-states as an intermediary stage of modernity which should end with multinational societies – of which USSR was not a part, according to Mamardashvili. But above all, Mamardashvili hated the Soviet state’s opposition to dialogue.

Join the conversation