I have recently helped to set up the College for Real Farming and Food Culture, the immediate aim of which is to promote the Agrarian Renaissance – a complete re-think of the way we farm and organize farming. This in turn is conceived as part of a grand, across-the-board Renaissance – a complete re-think of everything: farming, politics, the economy, science, and the moral and metaphysical precepts that underlie all the things we do and think about. The stated goal of this whole endeavour is to create “Convivial Societies within a Flourishing Biosphere”. I can’t think of anything better or more important than that.

So it is than on all big issues – nuclear power, the free market, and so on and so on – I tend these days to ask, “Do they contribute to the grand cause of convivial society, the wellbeing of our fellow creatures and the fabric of the Earth?”

And how, by this criterion, should we judge the undoubted propensity and predilection of human beings for forming ourselves into tribes?

In large part, of course, the answer depends on how we define “tribes”. In ancient times, when human beings were fairly thin on the ground, tribes were conceived, largely, in geographical terms. They were the people who happened to live in a particular territory, who grew up together, and in general were of the same ethnic group or indeed of the same family, and evolved common ways of speech and manners and rituals. Things were never quite as simple as that, of course, because some groups – including those that lived by following herds of grazing animals – were nomadic. Relations between tribes, whether static or nomadic, were sometimes positive, which mainly meant amicable trading, and sometimes anything but.

Nowadays, the world is more crowded and roughly half of us live in cities while most of the rest are farmers. Now, when communications are so much better than ever before and we are dominated by the “global economy”, very few people live in traditional tribes. But we remain very tribal nonetheless. So it is that Londoners, at least in those areas that still have fairly settled populations, tend to divide themselves into neighbourhoods, each with a recognizable character: Brixton, Dulwich Village, East Dulwich, Greenwich, Stepney, Chiswick, Hampstead, and so on. Others tribes are formed through common interest: the Royal College of Obstetricians, small farmers, supporters of Manchester United, Muslims, Roman Catholics or Seven-day Adventists.

But are such tribe-like groupings a good thing?

Well, it depends in large measure how the tribes define themselves. We can draw a parallel between tribes and species.

Biologists have long wondered how it is that species in the wild – even those that look very similar – generally mate only with their own kind. In truth there are quite a few inter-species hybrids in nature. Bread wheat, for example, is a hybrid of three different ancestral grasses, and it now seems that modern Europeans contain quite a few Neanderthal genes. But most mating between animals of different species usually produces no offspring, or else the offspring are in some way deficient, so it’s best to keep themselves to themselves.

The great Harvard zoologist Ernst Mayr suggested that species usually manage to avoid miscegenation because there are mating “barriers” between them. On the whole dogs don’t fancy cats, and vice versa. But in the 1980s the South African biologist Hugh Paterson suggested that this was the wrong way to look at things. Species surely don’t define themselves by their differences, or the “barriers”, between them. They define themselves by what they have in common. Animals consider themselves to be of the same species, said Paterson, if they recognise each other’s specific mating signals.

The same kind of reasoning may define the distinctions between tribes. Are Muslims Muslims because they are different from Christians and from Jews, or because they all follow the prophet Muhammad? The former implies a barrier between the different groups. The latter does not.

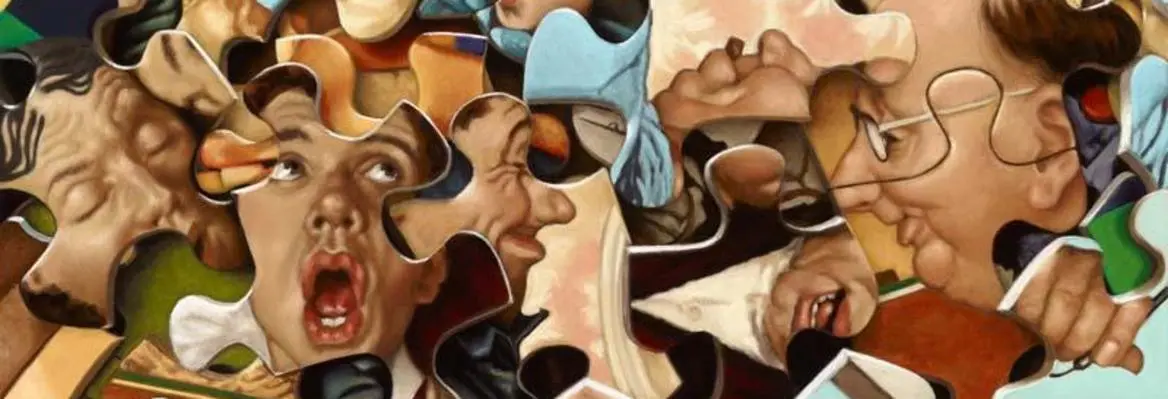

The Art of Community

Are tribes dangerous, or essential to society?

Issue 55, 10th April 2017

Want to continue reading?

Get unlimited access to insights from the world's leading thinkers.

Browse our subscription plans and subscribe to read more.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Latest Releases

Join the conversation