In their seeking of simplicity, scientists fall into error. They mistake their abstract concepts describing reality – for reality itself. The map for the territory. This leads to dogmatic overstatements, paradoxes and mysteries such as quantum gravity. To avoid such errors, we should evoke the thinking of philosopher Alfred North Whitehead and conceive of the universe as a universe-in-process, where physical relations beget new physical relations, writes Michael Epperson.

When celebrity physicists disagree about some fundamental prediction or hypothesis, there’s often a goofy and well-publicized wager to reassure us that everything is under control. Stephen Hawking bets Kip Thorne a one-year subscription to Penthouse that Cygnus X-1 is not a black hole; Hawking and Thorne team up and bet John Preskill a baseball encyclopedia that quantum mechanics would need to be modified to be compatible with black holes. Et cetera, et cetera. And even as we roll our eyes, we’re grateful because at least some part of us does not want to see these people violently disagreeing about anything.

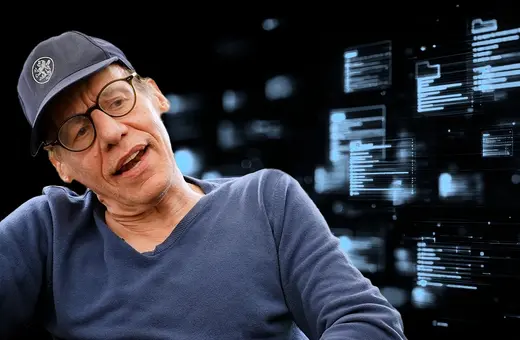

So when celebrity physicist Lawrence Krauss publicly called celebrity physicist David Albert a “moron” for not appreciating the significance of Krauss’s discovery of the concrete physics of nothingness, it caused quite a stir. In his book, A Universe from Nothing, Krauss argued that in the same way quantum field theory depicts the creation of particles from a region of spacetime devoid of particles (a quantum vacuum), quantum mechanics, if sufficiently generalized, could depict the creation of spacetime itself from pure nothingness. In a scathing New York Times review of Krauss’s book, Albert argued that claiming that physics could concretize “nothing” in this way was at best naïve, and at worst disingenuous. Quantum mechanics is a physical theory, operative only in a physical universe. To contort it into service as a cosmological engine that generates the physical universe from “nothing” requires that the abstract concept of “nothing” be concretized as physical so that the mechanics of quantum mechanics can function. What’s more, if quantum mechanics is functional enough to generate the universe from nothing, then it’s not really nothing; it’s nothing plus quantum mechanics.

This is a familiar maneuver in popular physics books these days—claims of concretizing what is inescapably abstract, usually by way of a purely speculative and untestable assertion costumed mathematically as a testable hypothesis.

This is a familiar maneuver in popular physics books these days—claims of concretizing what is inescapably abstract, usually by way of a purely speculative and untestable assertion costumed mathematically as a testable hypothesis. It is a cheap instrument, as attractive as it is defective, used more often as cudgel than tool for exploration. Fortunately, as we saw with David Albert, few despise its dull edge more than other physicists and mathematicians. During the first years of modern mathematical physics and the construction of its two central pillars, quantum theory and relativity theory, Alfred North Whitehead warned, “There is no more common error than to assume that, because prolonged and accurate mathematical calculations have been made, the application of the result to some fact of nature is absolutely certain.”

Join the conversation