When it comes to exploration, robots can outperform astronauts at a far lower cost and without risk of human life. Why, then, do so many people conceive of space exploration as the domain of humans rather than robotic explorers? Martin Rees and Donald Goldsmith explore why robots are the future of space exploration.

How much do we need humans in space? How much do we want them there? Astronauts embody the triumph of human imagination and engineering. Their efforts shed light on the possibilities and problems posed by travel beyond our nurturing Earth. Their presence on the moon or on other solar-system objects can imply that the countries or entities that sent them there possess ownership rights. Astronauts promote an understanding of the cosmos and inspire young people toward careers in science.

SUGGESTED READING

Billionaires in space

By Tony Milligan

SUGGESTED READING

Billionaires in space

By Tony Milligan

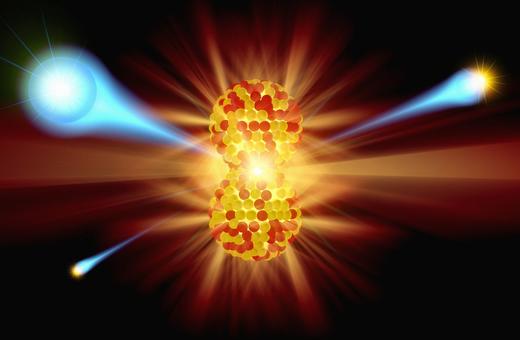

When it comes to exploration, however, our robots can outperform astronauts at a far lower cost and without risk of human life. This assertion, once a prediction for the future, has become reality today, and robot explorers will continue to become ever more capable, while human bodies will not. Fifty years ago, when the first geologist to reach the moon suddenly recognized strange orange soil (the likely remnant of previously unsuspected volcanic activity) no one claimed that an automated explorer could have accomplished this feat. Today we have placed a semiautonomous rover on Mars, one of a continuing suite of orbiters and landers, with cameras and other instruments that probe the Martian soil, capable of finding paths around obstacles as no previous rover could. The first helicopter flight achieved in another body’s atmosphere marks the opening of new methods of exploration. NASA has plans to search for signs of ancient or even present-day life on Mars by bringing carefully selected samples of Martian soil back to Earth. Our robot explorers have visited all the sun’s planets (including that former planet Pluto), as well as two comets and an asteroid, securing immense amounts of data about them and their moons, most notably Jupiter’s Europa and Saturn’s Enceladus, where oceans that lie beneath an icy crust may harbor strange forms of life. Future missions from the United States, the European Space Agency, China, Japan, India, and Russia will only increase our robot emissaries’ abilities and the scientific importance of their discoveries. Each of these missions has cost far less than a single voyage that would send not robots but humans, which in any case remains an impossibility, for the next few decades, for any destination save the moon and Mars.

Why, then, do so many people conceive of space exploration as the domain of human rather than robotic explorers? Here we may cite six chief factors, often interrelated:

Tradition: From Marco Polo to Columbus, from Ernest Shackleton to Yuri Gagarin and Neil Armstrong, we conceive of exploration as requiring the direct engagement of humans.

Engagement: We naturally relate to humans far more than to machines, though we may identify, to some degree, with the latter, from the Little Engine that Could to the rovers on Mars to the James Webb Space Telescope.

Adventure: The difficulties and dangers of exploration bring a dramatic tension that has always appealed to us. If Columbus had merely sailed the Atlantic to visit friendly nations in the Americas, his voyages would hardly have captured as much attention from European powers.

Join the conversation