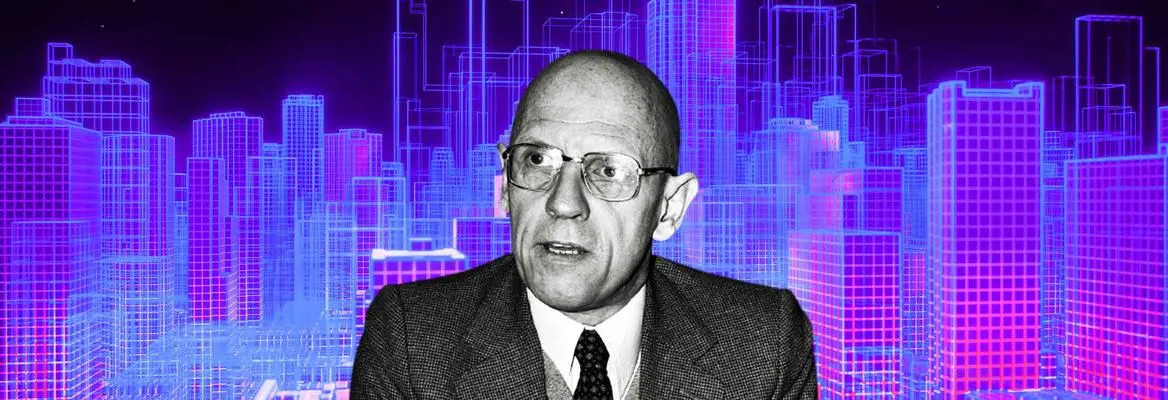

The 15 minute city has become a byword for modern planning, sustainability and the good life. To some it is a conspiracy designed to keep people in their place. However, through an understanding of Foucault, the allure of the 15 minute city is shown to be a modernist solution to a postmodern world writes professor Mark G.E. Kelly.

The concept of the 15-minute city, though based on rather older ideas in urban planning, has risen to quite sudden prominence in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, having been first proposed as a way to improve cities that leans into the pandemic-associated movement restrictions by trying to reimagine urban living to eliminate lengthy commuting, and then become in turn a magnet for conspiracy theories that already understood the very pandemic itself as an exercise in social engineering. In sorting out this mess, I would recommend you to consider the thought of Michel Foucault, who understood contemporary societies in terms of the interaction of power and knowledge to discipline the bodies of individuals and thereby minutely to regulate populations, as allowing a critical view of such ideas that does not require us to believe in a grand conspiratorial narrative.

SUGGESTED READING

Schopenhauer vs Hegel: progress or pessimism?

By Joshua Foa Dienstag

SUGGESTED READING

Schopenhauer vs Hegel: progress or pessimism?

By Joshua Foa Dienstag

In particular, I want to consider the concept of the 15-minute city in this regard as a form of utopian scheme, a form of knowledge production that serves strategies of power in our society. Foucault consistently opposed utopianism. One might even suggest this is a signature of his approach, were it not that his anti-utopianism is the fulfilment of a long anti-utopian tendency in European/continental/left thought, which one can trace back to Karl Marx in particular (think of his critical chapter on ‘utopian socialists’ in the Communist Manifesto, and his refusal to articulate any positive vision of communism).

Utopianism is typically associated with grand schemes for reforming society. At what point, however, does politics become ‘utopian’? I tend to think the slippage from policy to utopianism occurs extremely readily, to the point that any and all politics ought to be assumed to be utopian. This is because any attempt to plan anything involves the development of an idealised conceptual plan for reality that does not match what we will get when the plan is put into effect. Indeed, Foucault once declared the sole moral imperative he would prescribe was ‘never to do politics’.

We are sometimes told that policy can and should be ‘evidence-based’. This proposition is itself not based on any kind of evidence, either for its empirical applicability or even for its normative desirability given the inapplicability of evidence to form any policy at all, given the complexity of social systems. That is to say that, even if you have evidence that a policy works in a particular context, say in one country, any other situation in which you attempt to apply it is likely to be sufficiently different that you will not know whether it will yield the same result.

___

One might say that the 15-minute city concept is benign precisely because it does not entail any particular policy. This, I would suggest, make it at best vacuous and at worse insidious.

___

Join the conversation