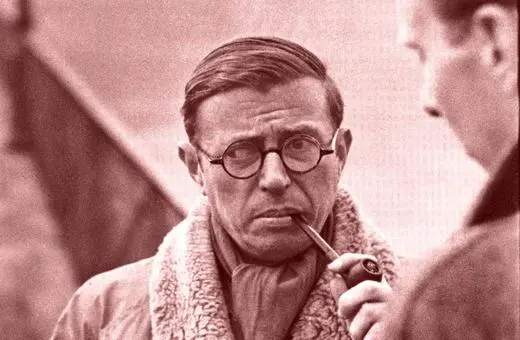

The question of what an ideally just society looks like has been one of the perennial philosophical questions. In recent decades, it has essentially dominated the field of analytic political philosophy. Charles W. Mills, a distinguished philosopher who passed away on 20 September 2021, believed that was a mistake. An exclusive focus on the conditions of ideal justice meant ignoring the injustices of the real world, treating them as incidental rather than structural in nature. In exposing the ways in which ideology, oppression and racism can be systematic barriers to achieving the goal of justice, Mills cemented injustice as a philosophical problem worthy of study as much as any, writes Jason Stanley.

Pressed for a definition of the discipline of philosophy, some might provide it as the study of the nature of truth, beauty, goodness, knowledge, wisdom, virtue, skill, and justice. Such a conception of philosophy seems to be borne out by its history – the central question of Plato’s Republic is, after all: what is justice? But if philosophy is an investigation of (say) the different possible ideals of justice, or the nature of knowledge, what does philosophy have to say about the persisting nature of injustice and ignorance? Is it a philosophical issue, a matter for the field of philosophy, to explain? Is there a systematic structure to injustice, a set of puzzles and contradictions the study of which is characteristic of philosophical inquiry?

According to Charles W. Mills, one of the most eminent philosophers of the last half century, the answer is, resoundingly, in the affirmative. Mills argued powerfully that philosophy must study injustice, oppression, and ignorance as subjects in their own right. In his work, Mills argues that the failure to do so, to characterize political philosophy as simply the study of which form of justice a perfect society should aim towards, is in fact a pernicious ideological project – tantamount to whitewashing oppression, by relegating the study of its history and nature to a secondary task. If the study of barriers to justice and knowledge is not “philosophical”, that suggests that such barriers are incidental and temporary – Mills is adamant they are not.

Mills began his career as a Marxist, and Marxist thought pervasively influenced his thinking throughout, alongside feminist critiques of liberalism. But the barrier to justice that Mills devoted most of his work to investigating is race, which he rightly argued structured the modern world, a world built from racial slavery, colonization, and genocide. In Mills’ work, we find a powerful case for the claim that race is a foundational philosophical concept.

Mills’ most famous book, The Racial Contract, forcefully presents his critique of contemporary analytic political philosophy for ignoring the philosophical significance of race, for idealizing away from it. Mills demonstrates how these idealizations draw us systematically away from topics that were in fact always central to political philosophy, such as ideology and oppression. In his work, he urges us to attend not just to the philosophical significance of normative ideals, but to the philosophical significance of barriers to achieving these ideals – that is, to ideology. As he writes:

Mills’ most famous book, The Racial Contract, forcefully presents his critique of contemporary analytic political philosophy for ignoring the philosophical significance of race, for idealizing away from it.

Join the conversation