"And now what will become of us without barbarians? / Those people were a kind of solution."

—C. P. Cavafy, “Waiting for the Barbarians” (1898)

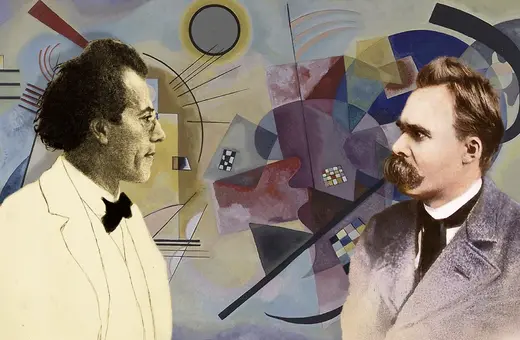

Perhaps you know this poem? Constantine Cavafy was a writer whose every identity came with an asterisk, a quality he shared with Italo Svevo. Born two years after Svevo, he died only a few years after him. Cavafy was a Greek who never lived in Greece. A government clerk of Eastern Orthodox Christian upbringing in a tributary state of a Muslim empire that was under British occupation for most of his life, he spent his evenings on foot, looking for pagan gods in their incarnate, carnal versions. He was a poet who resisted publication, save for broadsheets he circulated among close friends; a man whose homeland was a neighborhood, and a dream. Much of his poetry is a map of Alexandria overlaid with a map of the classical world— modern Alexandria and ancient Athens— in the way that Leopold Bloom’s Dublin neighborhood underlies Odysseus’s Ithaca. No single sentence captures this Alexandrian genius better than E. M. Forster’s evocation of him as “a Greek gentleman in a straw hat, standing absolutely motionless at a slight angle to the universe.” 1 And I conjure Cavafy, here, at journey’s end, because I want to persuade you that he is representative precisely in all his seeming anomalousness.

Poems, like identities, never have just one interpretation. But in Cavafy’s “Waiting for the Barbarians” I see a reflection on the promise and the peril of identity. All day the anticipation and the anxiety build as the locals wait for the barbarians, who are coming to take over the city. The emperor in his crown, the consuls in their scarlet togas, the silent senate and the voiceless orators wait with the assembled masses to accept their arrival. And then, as evening falls, and they do not appear, what is left is only disappointment. We never see the barbarians. We never learn what they are actually like. But we do see the power of our imagination of the stranger. And, Cavafy hints, it’s possible that the mere prospect of their arrival could have saved us from ourselves.

___

"Our largest cultural identities can free us only if we recognise that we have to make their meanings together and for ourselves."

___

The labels we adhere to, the labels that adhere, willy- nilly, to us, work through and in spite of the mistakes we make about them. Cavafy was not exactly gay, not exactly Greek or Egyptian, not exactly Orthodox or pagan. But each of these labels tells you something about him, if you listen carefully to his own inflection of these modes of being. And Cavafy’s Alexandria, like Svevo’s Trieste, like the marvelous city I live in, was exactly the sort of cultural hodgepodge that could provide the space for him to be each of these things in his own way, negotiating with his friends and acquaintances, struggling with his city; it allowed him to shape a self that was not merely captured but also liberated by the identities that enmeshed him.

Our largest cultural identities can free us only if we recognize that we have to make their meanings together and for ourselves. You do not get to be Western without choosing your way among myriad options, just as you do not get to be Christian or Buddhist, American or Ghanaian, gay or straight, even a man or a woman, without recognizing that each of these identities can be lived in more than one way.

Cavafy’s own community— cosmopolitan Alexandria— has long since vanished; the end of the British protectorate and the rise of Arab nationalism made the city less hospitable to its motley crew of strangers.

Join the conversation