A developing narrative about why Putin invaded Ukraine is that his thinking was influenced by fascist Russian philosophers. But that account is both reductive and lacking in evidence. Alexander Dugin, the man who’s been called the brains behind Putin, has no direct connection to the Kremlin, and his overall influence is hugely exaggerated. Ivan Ilyin, the other philosopher who is said to have influenced Putin’s thinking, is a more plausible candidate but in his case the label ‘fascist’ is a caricature, at odds with a large part of his philosophy. Calling thinkers or political leaders fascist is an easy way to dismiss them out of hand, blocking a deeper understanding of Putin’s real motives and the ideas that have informed his world view, argues Paul Robinson.

As people seek to understand Russian president Vladimir Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine, one explanation that has become popular is that the Russian leader is a “fascist.” This idea promotes a binary view of the world as divided between good and evil. It is, however, misleading and perhaps even harmful.

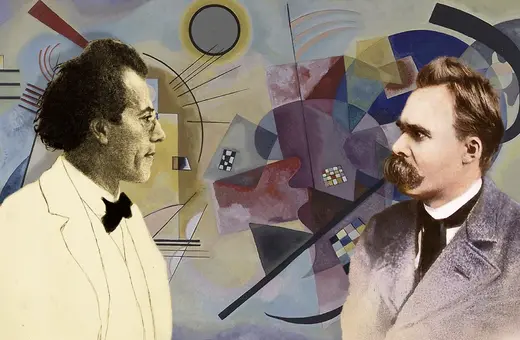

To justify the fascist label, commentators have noted Putin’s affection for inter-war émigré philosopher Ivan Ilyin and linked this to claims that Ilyin was a fascist. The logic is simple: Putin likes Ilyin; Ilyin was a fascist; ergo, Putin is a fascist. Pundits also draw parallels between Putin and contemporary Russian thinker Alexander Dugin, who has also been called a fascist. Thus, Juliet Samuel writes in The Daily Telegraph that, “Ilyin saw in Mussolini and Hitler models for the reinvention of a new Russian tsarism … Today the task of popularising this sort of messianic fascism falls to a movement called Eurasianism, propounded by a zealous supporter of Putin named Alexander Dugin, who appears with regularity on Russian TV screens.”

___

___

The primary source for stories linking Putin, Ilyin, and fascism is Yale historian Timothy Snyder, who claimed in his 2018 book The Road to Unfreedom that Ilyin was the inspiration behind Putin’s policies. Snyder says that, “Putin relied upon Ilyin’s authority to explain why Russia had to undermine the European Union and invade Ukraine.” The problem is that Putin did not do so, there being no public record of him ever mentioning Ilyin with reference to either the European Union or Ukraine. Likewise, contrary to what Samuel says, Dugin does not appear “with regularity on Russian TV screens.” He is a fringe figure whose contacts with the Russian state have long since been ruptured. Dugin himself admits, “I have no influence. I don’t know anybody, have never seen anything. I just write my books, and am a Russian thinker, nothing more.” The idea that Dugin is “Putin’s Brain” is far-fetched.

Talk of Eurasianism is equally misleading. As one of that movement’s founders, Pyotr Savitsky, wrote in 1921, Eurasianism’s basic idea is that, “Russia is not only the ‘West,’ but also the ‘East,’ not only ‘Europe,’ but also ‘Asia,” and even not Europe at all, but ‘Eurasia’.” But speaking in October 2017, Putin remarked that while Russia was geographically Eurasian, “as regards culture … this is all undoubtedly a European space as it is inhabited by people of that culture.” Putin has several times quoted the Eurasianist thinker Lev Gumilyov, but in the context of stressing Russia’s multi-ethnic nature. He has never indicated support for broader Eurasianist thought.

___

___

Join the conversation