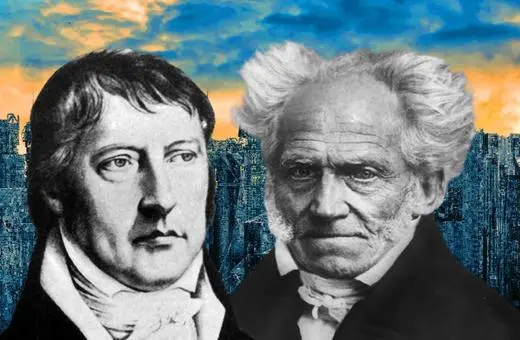

Bertrand Russell and G.E. Moore saw their revolt against Hegelian idealism, and their embrace of realism, as ushering in a ‘new philosophy’, what eventually became known as ‘analytic philosophy’. For Hegel and his followers, reality only made sense as a whole: to understand anything you needed to understand how it was a manifestation of reality overall. Russell and Moore, on the other hand, thought that science and common sense taught us that reality is made of individual things that can be understood on their own, separately from everything else. This metaphysical picture, however, depended on an epistemological one: direct realism. According to Russell, we come to know about the world by direct acquaintance with its objects. As it turns out, a critique of that position lies at the foundation of Hegel’s thought, a critique that continues to haunt analytic philosophy today, writes Fraser MacBride.

In the late 1890s the Cambridge philosophers G.E. Moore and Bertrand Russell made a remarkable and creative leap forward—their ‘discovery’, they declared, was of the principles underlying what they called their ‘New Philosophy’. According to this philosophy, reality consists of a mind independent plurality of separate, independently existing entities. They are entities which, when we perceive them, are given to us immediately or directly, so without relying upon our having any mediating ideas or internal representations of them, hence given to us without any conceptual trappings of our mental making.

___

What especially captivated the British idealists was Hegel’s belief that separateness is ultimately an illusion.

___

Moore and Russell called their philosophy ‘new’ because they believed its discovery marked a decisive break in history; they envisaged their philosophy would sweep away all of its predecessors. Even though other philosophical traditions endured and indeed others flourished later, their youthful confidence was far from being entirely misplaced. Their New Philosophy was destined to become one of the contributing streams, one of the most significant, that fed into what was to become that great intellectual river system, analytic philosophy. Nonetheless, a key idea from the Hegelian philosophy they were revolting against would continue to pose a challenge to their realist shift.

The resurgence and death of Hegelian philosophy?

Join the conversation