Could you ever hope to observe – visually or otherwise – the conscious experiences of others? Before venturing an answer to this question, it is important to understand what is being asked and why answers have proved so elusive.

Philosophers, psychologists, and neuroscientists vigorously debate solutions to what David Chalmers calls the Hard Problem of consciousness: how are conscious experiences to be reconciled with our emerging understanding of the material world? Many who accept that consciousness has a neurological ‘substrate’ reject the reduction of the mental to the physical because this seems effectively to eliminate the mental. On the one hand, we seem intimately familiar with qualities of our conscious experiences, experiences that mediate our awareness of the physical universe. On the other hand, the qualitative nature of these experiences seem altogether to elude the physical sciences. From the scientific perspective, conscious phenomena seem alien and utterly mysterious.

We face a dilemma. Conscious qualities appear to reside alongside the physical realm, so we seem bound to accept to some brand of unsavory dualism. Including conscious qualities amongst states and events of the kind studied by the physical sciences, however, obliges us to ignore everything that makes them so distinctive.

The acuteness of the Hard Problem is thought to result from two widely advertised features of conscious experiences.

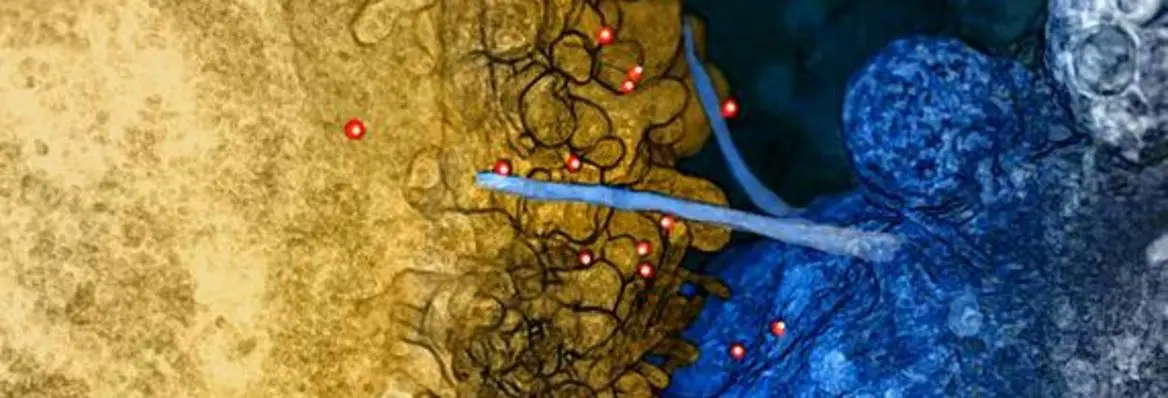

First, conscious experiences differ qualitatively from physical states and processes. (To simplify the discussion, I shall ignore differences among observers – color blindness, for instance – and variations in conditions under which objects are observed. These are irrelevant to what is at issue here.) Even if you allow that your experience of a red tomato is intimately related to goings on in your brain – conscious states are thought at a minimum to be correlated with neurological processes – the qualities of this experience appear to be nothing like qualities encountered by scientists who spend their careers studying brains. There is ‘something it is like’ to have a visual experience of a ripe tomato, for instance, and this is nothing at all like what you come across when you examine, by whatever means, the brain of someone undergoing the experience.

The problem of conscious qualities – the ‘qualia problem’ – is taken to be particularly vexing because it is difficult to imagine any physical discovery revealing anything remotely like qualities of familiar conscious experiences. So even if we post-Cartesians are confident that brains are the source of consciousness, an account of how this is supposed to work appears hopelessly out of reach.

Second, conscious experiences are ‘subjective’. In addition to there being ‘something it is like’ to undergo a particular conscious experience, every conscious experience is ‘like something’ only to whomever or whatever undergoes it. Your relation to the qualitative character of your own experiences is privileged, at least in the sense that there is a fundamental asymmetry between your ‘access’ to your own experiences and anyone else’s. Your access is ‘direct’, unmediated; the access of others is indirect and inferential.

These two aspects of consciousness effectively bifurcate the universe along two axes. On the one hand, conscious qualities differ from physical properties. On the other hand, conscious qualities, unlike physical phenomena, can only be apprehended from the ‘inside’, from a subjective ‘first-person perspective’. Sciences that provide our best portraits of the physical universe take up an objective perspective that is notably ill-equipped to tackle an essentially subjective domain. Science encounters conscious experience only from the ‘outside’, the distinctive subjective ‘inner’ character of experience remaining, like the horizon, forever out of reach.

___

Join the conversation