Humanity’s search for a theory of everything is one of the motivating forces behind the whole scientific endeavour. But is it possible for an observer within the universe to know everything about the universe? Philosopher of science JB Manchak here argues that we cannot know the structure of all of spacetime from any specific point within it – and this is the case even if we somehow collected all the possible perspectives, from every point in the universe. Due to arguments made available by Einstein’s general relativity, we cannot know the universe from within it.

It is well known that the region beyond the 'observable universe' is unknowable. What is less well known is this: even if one were somehow able to observe this unobservable region, the universe would remain unknowable. Indeed, the puzzling state of affairs would persist even if one were given an all-access pass to every possible observation at every possible place and time -- here, there, past, present, and future.

In what follows, I will argue that there is a sense in which the universe is fundamentally unknowable via any number of observations made from within it. This claim amounts to a theorem of Einstein's general theory of relativity and the argument amounts to a simple proof sketch of this theorem. Only a few key definitions will be needed to state the theorem and sketch the proof.

SUGGESTED VIEWING

Imagining the universe

With Iain McGilchrist, Roger Penrose, Esther Freud, Eliane Glaser

Let's start with the notion of a four-dimensional spacetime. This is a model of general relativity that represents a possible universe compatible within the theory. One can think of a spacetime as a collection of events with some additional structure that specifies how the events are related. One's birth and one's death are events. A first kiss is an event. The moon landing is also an event. But July 20, 1969 is not an event. And the moon is not an event.

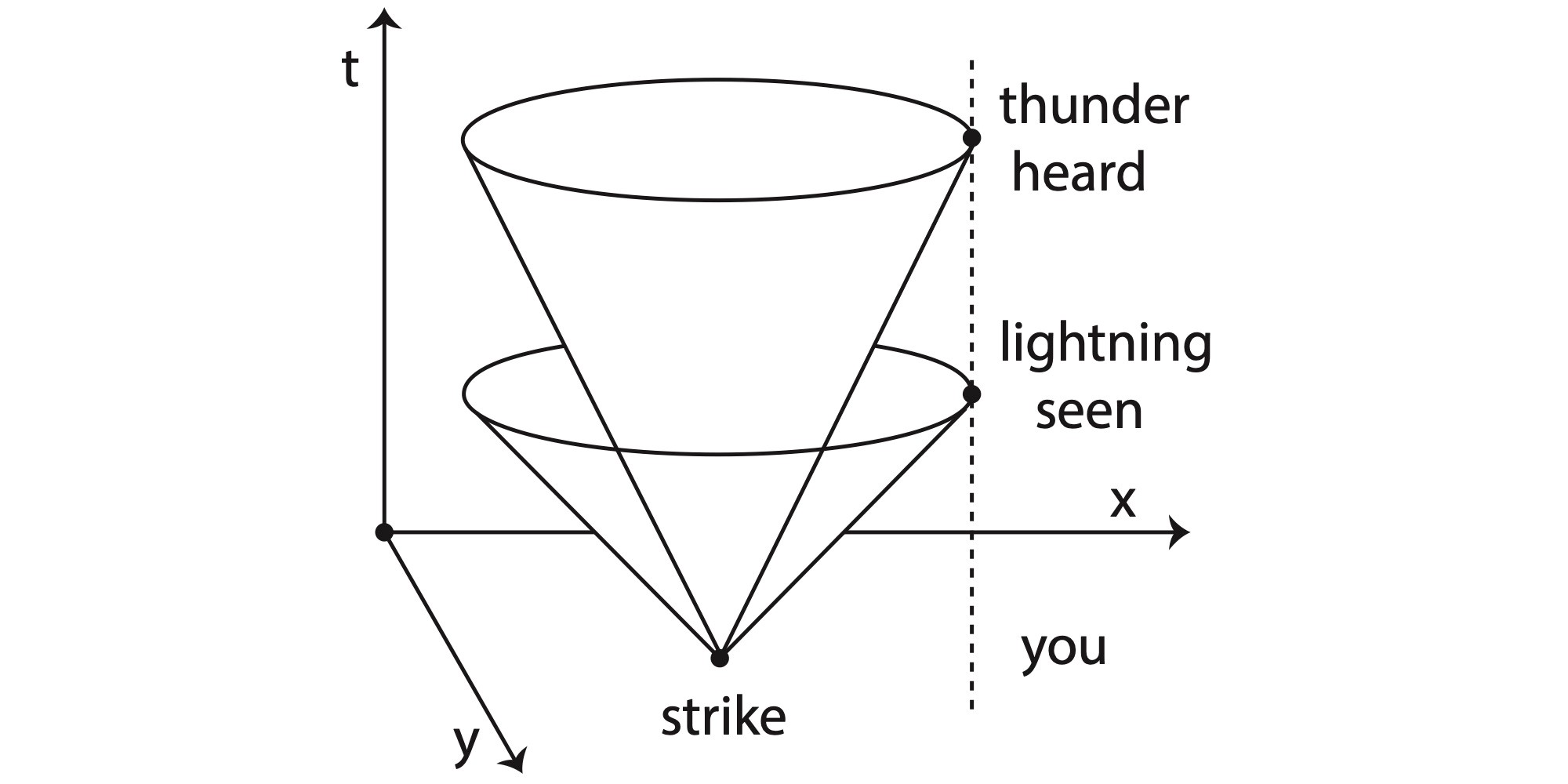

Experience seems to tell us that any event can be characterized by four numbers: one temporal coordinate t and three spatial coordinates x,y,z. Accordingly, the local structure of spacetime resembles a four-dimensional Cartesian coordinate system. Diagrams can help us 'see' this spacetime structure. Consider the spacetime diagram of a lightning strike for example.

Following a long tradition, the time axis t is vertical with the up arrow pointing in the future direction. Two spatial dimensions x and y are also depicted with the z dimension suppressed. Just after the event of the strike, light propagates radially outward in all spatial directions. The uniform speed of light has the effect of producing a cone shape in the future direction of spacetime. The thundering sound of the strike creates a similar structure. The future 'sound cone' fits inside the future 'light cone' because the speed of light is so much faster than that of sound. Suppose you are standing nearby. At any particular time, you are located at a particular point in space. When all of the you-at-a-time points are stacked together, the resulting 'world-line' is a smooth curve in spacetime: the four-dimensional you. Naturally, you will see the lightning before hearing the thunder. How much time passes between these two events will depend on how far away you are from the strike; the further away, the more time will separate the two events.

___

At any given time, humanity is a collection of disconnected bodies in three-dimensional space. In four-dimensional spacetime, however, humanity is a single entity.

___

Join the conversation