The recent disaster has exposed serious shortcomings in economic strategy and public policy. But the current economic collapse will lead us to a brighter tomorrow, writes Jeffrey Miron.

The economic and health impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic continue to reverberate around the globe. With 17 million reported cases – 6 million active – and nearly 700,000 deaths worldwide, victory remains distant. Here in the United States, with a second wave hitting many states and generating more cases and deaths each day, the hope for a flattened curve – let alone containment – is meager.

SUGGESTED READING

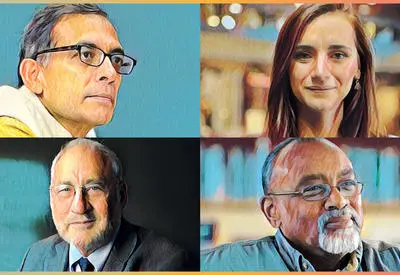

Groundbreaking economics at HowTheLightGetsIn

By

Four months into this pandemic, however, enough time has passed to draw early lessons from the crisis and perhaps even find silver linings.

SUGGESTED READING

Groundbreaking economics at HowTheLightGetsIn

By

Four months into this pandemic, however, enough time has passed to draw early lessons from the crisis and perhaps even find silver linings.

Covid-19 magnified private and public-sector inefficiencies, unpreparedness, and policy failures Government agencies scrambled to respond to the new threat, but miscommunication and unnecessary regulatory barriers hamstrung their efforts. Fortunately, the current crisis is leading to widespread rollbacks of unnecessary, restrictive policies. Making these changes permanent will improve future outcomes, and our economic model will become stronger without strangling bureaucracy.

With the benefit of hindsight, we can see how these agencies created unnecessary roadblocks and restructure them in a manner beneficial to future public health and economic prosperity.

Perhaps the greatest impediment to the United States’ early coronavirus response was the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Although on paper the FDA is responsible for “protecting the public health” and “advancing the public health by helping to speed innovations,” missteps at the FDA and Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) caused delays in testing, procurement of critical resources, and restrictions in access to healthcare. Now, with the benefit of hindsight, we can see how these agencies created unnecessary roadblocks and restructure them in a manner beneficial to future public health and economic prosperity.

Containment of Covid-19 is difficult without a robust testing infrastructure. But contaminated reagents in the initial diagnostic testing kits produced and distributed by the FDA generated confusion about correct interpretation of the tests. The faulty FDA tests and a prohibition on tests manufactured by private companies – domestically or overseas – led to an overall shortage, prevented many symptomatic individuals from getting tested – one of the reasons for the virus’ spread.

The FDA was also slow to address the shortage of ventilators. Even as hospitals resources were stretched thin, FDA regulations prevented the manufacture and use of innovative new alternatives.

A doctor in Mississippi designed ventilators that could be quickly and cheaply made from common materials, but they were not authorized under FDA regulations. Even minor adaptations to already approved medical devices were prohibited until March 24, at which point the United States had already seen more than 1,000 fatalities. Faced with mounting evidence that current policies – including those prohibiting or limiting who could modify or repair critical life-saving equipment – could exacerbate equipment shortages or even lead to patients dying, the government needed to end these restrictive policies.

Another area where regulation slowed the pandemic response was the early shortage of hand sanitizer. Distilleries around the nation transitioned from producing spirits to manufacturing and distributing hand sanitizer. But these efforts ran afoul of regulations controlling the production and sale of alcohol-based cleaning products. The FDA did relax the restrictions, but only after non-trivial delays. More importantly, why were there regulations in place at all?

Join the conversation