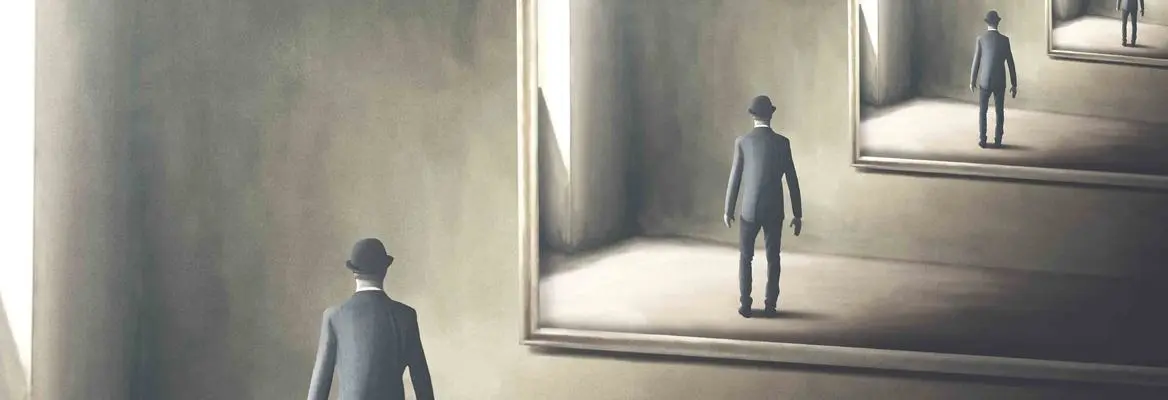

Self-deception is a part of the human condition. Tragedy is not just terrible luck, but our capacity to knowingly/unknowingly deceive ourselves into doing the very things we wanted to avoid. This aspect of human agency, our reluctance to sometimes see the things that are right in front of us, is fundamental to understanding Sophocles’ Greek tragedy ‘Oedipus the King’, but also, ultimately, understanding ourselves, writes Simon Critchley.

We usually think of tragedy as a misfortune that simply befalls a person (an accident, a fatal disease) or a polity (a natural disaster, like a tsunami, or a terrorist attack like 9/11) and that is outside their control. But if “tragedy” is understood as misfortune, then this is a significant misunderstanding of tragedy. What the thirty-one extant Greek tragedies enact over and over again is not a misfortune that is outside our control. Rather, they show the way in which we collude, seemingly unknowingly, with the calamity that befalls us.

Tragedy requires some degree of complicity on our part in the disaster that destroys us. It is not simply a question of the malevolent activity of fate, a dark prophecy that flows from the inscrutable but often questionable will of the gods. Tragedy requires our collusion with that fate. In other words, it requires no small measure of freedom. It is in this way that we can understand the tragedy of Oedipus. With merciless irony (the first two syllables of the name Oedipus, “swollen-foot,” also mean “I know,” oida), we watch someone move from a position of seeming knowledge—“I, Oedipus, whom all men call great. I solve riddles; now, Citizens, what seems to be the problem?” (I paraphrase)—to a deeper truth that it would appear that Oedipus knew nothing about: he is a parricide and a perpetrator of incest. On this reading, which Aristotle endorses, the tragedy of Oedipus consists in the recognition that allows him to pass from ignorance to knowledge.

Tragedy requires some degree of complicity on our part in the disaster that destroys us

But things are more complex than that as there’s a backstory that needs to be recalled. Oedipus turned up in Thebes and solved the Sphinx’s riddle after refusing to return to what he believed was his native Corinth because he had just been told the prophecy about himself by the oracle at Pytho, namely that he would kill his father and have sex with his mother.

Oedipus knew his curse. And, of course, it is on the way back from the oracle that he meets an older man who actually looks a lot like him, as Jocasta inadvertently and almost comically admits later in the play (line 742), who refuses to give way at a crossroads and whom he kills in a fine example of ancient road rage. One might have thought that, given the awful news from the oracle, and given his uncertainty about the identity of his father (Oedipus is called a bastard by a drunk at a banquet in Corinth, which is what first infects his mind with doubt), he might have exercised caution before deciding to kill an older man who seems to have resembled him.

One lesson of tragedy, then, is that we conspire with our fate. That is, fate requires our freedom in order to bring our destiny down upon us. The core contradiction of tragedy is that we both know and we don’t know at one and the same time and are destroyed in the process. It is a difficult, indeed, intolerable thought: How can we both know and not know?

Join the conversation